Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - February 12, 2021

From pinwheel to powerhouse

Every youngster from my generation at some time played with a pinwheel on a stick. It was somehow fascinating watching the

plastic blades whirl as I blew on them. Holding it out of a window of the family car meant the fun was continuous.

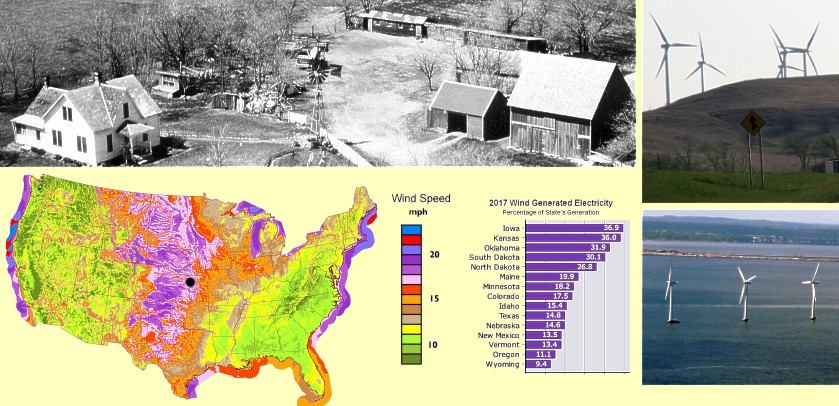

Its "big brother" was a familiar companion used to pump water on our farm. Electricity hadn't reached it when my parents were

married, making the windmill an important labor-saving device. Still, I always thought of the many windmills dotting the Kansas

prairie as more a remnant of the past than a precursor of the future.

But that began to change about 2000 during a visit to the former East Germany. Giant windmills were sprinkled here and

there, producing a sort of surreal landscape. On one quiet country road, husband Art stopped the car and we walked the access

drive until we were under the huge blades. We heard a vague humming sound and also a gentle "swoosh" when an individual blade

was nearest the ground, and so nearest us.

Today, we certainly don't have to do much traveling to see these big windmills, particularly in places noted for winds, such as

where the sea meets the land or the windy Great Plains. While they have found homes in Kansas fields and pastures, they can also

be seen on interstate highways in their disassembled state. Heading to Wisconsin last week, we saw frequent �Wide Load�

mini-convoys of three vehicles. A car sporting a yellow flashing light came first, then a truck with one of the windmill's

components and finally a trailing car that looked much like the first. Sometimes the lead vehicle had a tall flexible pole set

to the height of the tallest point of the truck's load and probing the area ahead to make sure there was adequate clearance

for the part in transit.

In the quest for energy to power our world modern, the only answer for years was to burn coal or hydrocarbons, such as oil and

natural gas. What was available from environmentally-friendly hydroelectric plants was woefully inadequate. Nuclear power was

once thought to be a non-polluting answer, but decades have passed since the first nuclear plant went online, and we have yet

to solve the problem of the radioactive waste they generate.

But solar power and wind power are now mounting a potent challenge to carbon-based energy generation. Those windmill parts we

saw heading down I-80 won't be pumping water to pastured cattle; they will be generating electricity!

Being an electrical engineer, it didn�t take much prompting for Art to share some facts as he has spent time in the

past satisfying his own curiosity:

- Two-bladed rotors wobble when spinning, but more blades increase the wind force against the tower. Three blades is the best

compromise.

- Most windmills have systems to turn the rotor so it faces into the wind.

- Rotating the blades changes the amount of surface the wind can push on and so adjusts the power output. If the blades are

turned so they are parallel to the wind, the rotor stops.

- Winds are steadier and stronger farther from the ground, so most towers are 300 feet tall. Blades are

typically 60- to 200-feet long. Useful wind speeds are in the 10- to 50-mph range.

- While they get bigger every year, a typical land-based unit today will generate 1,500,000 Watts (1.5 Megawatts) with a 30-mph

wind. In most windmills, the slowly-turning rotor is connected to a gear box whose output is at an increased speed. The generator

can be smaller if it is turned more rapidly.

- If winds were steady and optimal, it would take about 3,000 of today's typical windmills to provide all of Kansas' electrical

power - about one for every five-mile-by-five-mile piece of the state's land.

- Units are designed for a 25-year life and cost about $1 for every design Watt. So, a l.5 Megawatt unit costs a cool $1,500,000.

- The blades are made of a composite materials such as glass and carbon fibers. Each windmill has built-in status sensors to

monitor its health, but a human inspector/maintenance person visits three times per year. Those technicians have to be in good

shape because getting to the top is usually by steps!

- The biggest problem with the windmills is that the wind is not always blowing and so, does not always provide power when

needed. But even with this limitation, the windmills now contribute about eight percent of the total electrical energy we use.

Denmark was an early adopter of sea-based units and is home to Vestas, the biggest manufacturer of the turbine portion - the

part at the top of the tower that contains the generator. The first real �sea farm� with floating windmills is an installation

of five 6-Megawatt units 20 miles northeast of Scotland in 350 feet of water. The units float and are held in place by cables

attached to the sea floor. Electricity is brought ashore by an underwater cable.

While windmills are not bird-friendly, the bird fatalities at windmill farms are less than 10 percent of what they are at a

conventional power plant of the same capacity, where deaths are caused by high temperatures, being drawn into air intakes,

pollutants, etc. According to Wikipedia, these wind farms account for less than a millionth of those killed by cats, buildings or

automobile grills.

I must admit I enjoy watching the slow sweep of the blades, but am unsure how I feel about seeing them stretch across the once

open prairies. Still, the white house with the nearby red barn and small windmill that meant home to me as a child may have

been an affront to the Native Americans and Voyageurs who lived in Kansas before the Freelands arrived.

Daughter Mariya's name was inspired by a song from the 1950s musical, "Paint Your Wagon." One lyric from it is, "... Mariah

blows the stars around and sets the clouds a-flyin'." But things have changed since then. In 2021, we could add that it also

helps light our homes, cook our suppers and power our computers.