Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - January 8, 2021

Orderly ABCs

I've heard the pandemic advice to wash my hands for the length of time it takes to sing the ABC ditty twice - you know, the "A, B, C,

... Tell me what you think of me" one, or whatever version you learned. But it also started me thinking. I know the word "alphabet"

comes from the Greek letters alpha and beta, but when or how did we decide the order - that A comes before B and so on?

Alphabetical order is used to organize school attendance registers, dictionaries, telephone directories, and even grocery store

spice offerings. Daughter Mariya alphabetizes her collection of movies. Yet I began thinking about it in more detail when husband Art

and I were putting together the index of our book about Morganville, Kansas adopting F�ves, France after World War II.

Most items, such as people's last names, were no-brainers. First came Allen, then Anderson, then Arner, and so on. But what about

the 95th Infantry Division? Or the names of poems, such as "The Song of Hiawatha"? Some people put numbers at the end of the index,

while others place them where they would be if they were written as words. We opted to put numbered items at the beginning. We

also decided to keep the word "The" in titles of books, poems and songs, so those came under "T."

"A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order" by Judith Flanders whetted my appetite. She said a range of

other classification methods - geographical, chronological, hierarchical and categorical - were preferred over alphabetical order

for centuries.

She cited a study by Andrew Connor from the Centre for Ancient Cultures at Australia's Monash University, which found evidence of

alphabetical ordering in Greek administrative texts as early as the second century B.C. There is also evidence that the scrolls

in the Great Library of Alexandria, Egypt, founded around 300 B.C., were shelved in alphabetical groups by the first letter of

the author�s name.

But, she said, alphabetical order took a long time to come into ordinary use. Many people were illiterate, and monastical libraries

in the 12th and 13th centuries had only a few books, organized according to a hierarchical religious order.

It was hugely important the encyclopedias were in the order of God's creation because to not do that - to put angels, 'angeli,'

before God, 'Deus,' just because 'angeli' starts with A and God, 'Deus', starts with D - it not only meant that you probably weren't

very smart, you probably didn't understand God's creation ... Even worse, you might be a rebel, you might be trying to upend

hierarchy.

Another example Flanders gives is the 1086 Domesday Book, a summary of land occupancy in England and parts of Wales produced for

William the Conqueror. It assessed the values of more than 13,000 places, organizing them first by status. The king came first,

followed by clergy, barons, and poor tenants. Within each of those categories, they were arranged geographically.

Legal land descriptions in the U.S. are organized by their position compared to various arbitrarily-selected points. In Kansas,

that point is where Republic and Washington counties meet at the Nebraska-Kansas border.

Flanders said alphabetical ordering changed the notion that religion and social status were more important than other factors and

said we've come to rely on the alphabet because of its neutral nature. But not everyone was happy. In 1818, English romantic poet

Samuel Taylor Coleridge criticized the alphabetized Encyclopaedia Britannica as "a huge unconnected miscellany � in an arrangement

determined by the accident of initial letters."

Melville Dewey, an American librarian whose Dewey Decimal Classification system is still used in many libraries today, created what

he considered an improvement on alphabetical order. Flanders said Dewey thought he could take all the world's knowledge and give it

category numbers.

" ... He didn't know much about libraries," Flanders said. "... I'm not sure he really knew too much about the world, and he based

[his system] on an Anglo-centric, European-centric, Christian-centric worldview."

So what about other languages? For French, the last accent in a given word determines the order, so the following words would be

sorted as follows: cote, c�te, cot�, c�t�. In German, a letter with an umlaut (�, �, �) is treated just like its non-umlauted

versions. In the Swedish alphabet, of particular interest to me since I'm half-Swedish, there are three extra vowels placed at its

end (..., X, Y, Z, �, �, �). In Welsh, the language of Art�s paternal ancestors, CH, DD, FF, NG, LL, PH, RH, and TH are treated

as single letters, and each is listed after the first character of the pair (except for NG, which is listed after G).

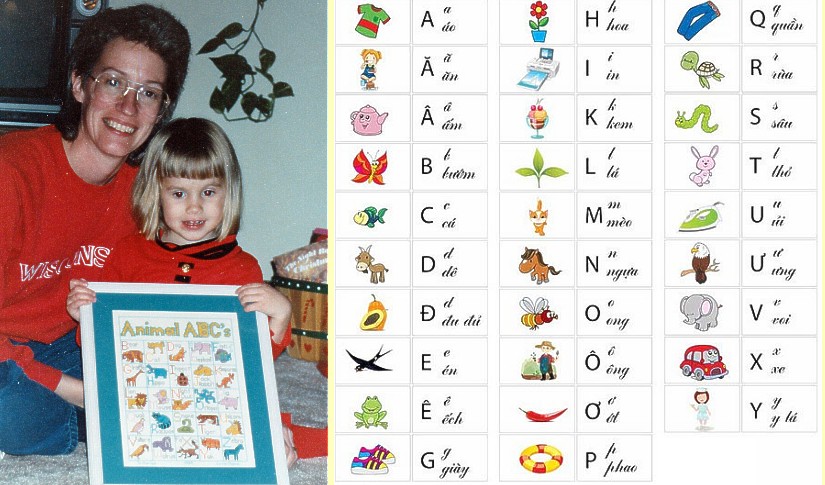

Non-Western languages present another challenge. Friend Huyen said Vietnamese, which adopted the Latin script, has seven additional

letters, while f, j, w and z are absent. Kiowa, a Native American language, is ordered on phonetic principles, rather than on the

historical Latin order, so vowels come first, then stop consonants ordered from the front of the mouth to the back, and from

negative to positive voice-onset time, then the affricates, fricatives, liquids, and nasals. Hmm. I must admit I don't even know

what those latter two groups are! More investigation needed here.

My reading indicated that rhymes have long been used to remember the letters, but the "A through Z" order of our alphabet is

apparently arbitrary. It reminds me of the way Art and I kid each other about objects we have left somewhere. "Why is that

screwdriver on the kitchen counter?" I ask. "Because everything has to be someplace," he answers.