Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - July 15, 2011

"Christmas every day"

Lunch time is usually a brief break in the day when we grab a bite to eat before returning to whatever it was we were doing before. So it's unlikely when Bob Hawley, sons Greg and Dave and contractor David Luttrell got together for lunch at friend Jerry Mackey's restaurant more than 25 years ago that they had any idea it would not only change their lives, but touch thousands of others as well.

At some point, the conversation turned to the steamboats that operated on the Missouri River in the 19th Century. Because the river is so shallow, shifting and full of snags, each voyage was a treacherous one. Boiler explosions were common on all steam vessels of that era, so when combined with the hazards posed by the river, the average Missouri steamer's lifetime was only about three years. But a single season's revenue could be five times the cost of construction, so there was no shortage of people willing to accept the risks.

More than a century after the railroad had all but extinguished the Missouri steamboat, the five men meeting at Mackey's restaurant decided it might be fun to try to salvage one and maybe make some money in the process.

They began by researching various vessels and eventually settled on the White Arabia. It had hit a snag just upstream from Kansas City on Sept. 5, 1856 and went down in about three minutes. But because the river was so shallow, everyone aboard escaped. The upper level of the vessel was still exposed when the wet passengers and crew began walking to a nearby village.

But the soft silt had fresh-water aquifers below, making the river bottom somewhat like quicksand. Within a couple of days, the ship had completely disappeared.

In 1987, the Hawleys set out to find the boat using old maps and a metal detector. The Missouri had changed course over the years and when the Arabia was found, it was located in a cornfield under 45 feet of silt, sand and soil. They were given permission to dig with the proviso that the work had to be completed before spring planting.

On Nov. 13, 1988, heavy equipment was brought in. Part of the work involved driving pipes into the ground around the wreck and connecting them to large pumps to keep the excavation from flooding.

Less than two weeks later, the boat was exposed. The first item discovered was a rubber overshoe. On Dec. 5, a wooden crate filled with beautiful china dishes was unearthed.

Day after day, the work continued. Leather hides, carpenter's tools, Wedgewood china and pickles still fit to eat were among the items recovered.

But the sheer amount and quality of the pieces changed the men. Rather than sell the artifacts as they had planned, they decided this treasure should be shared with the public. Consequently, the men and their families turned from simple treasure hunters into archaeologists, preservationists, historians and curators.

On Feb. 1, 1989, work ceased at the site, the pumps were turned off and the hole was filled. On Nov. 13, 1991, the Arabia Steamboat Museum opened. It immediately became the largest display of pre-Civil War frontier items in the world.

Husband Art, Venezuelan friend Ingrid and I visited the museum last weekend. I had been there in 2003 while on a national newspaper convention field trip, but I was just as amazed this time as I was eight years ago.

The museum's shelves are filled with beads, tools, school slates, coats, bolts of cloth, keys and many other items from Eastern states and foreign countries such as Belgium, Brazil, China, England, France, Italy and the West Indies. Near the recovered cargo is a full-size replica of the Arabia's main deck.

The Arabia's goods had been bound for settlers' homes as well as for tailors, cobblers, carpenters and general store owners. The find changed the opinions of historians who previously thought only the crude essentials of daily life would have been found on the frontier. The presence of items such as a 107-yard bolt of silk, furs, china, nutmeg, porcelain buttons and French perfume proved that a whole range of goods was available.

A visit to the Arabia Steamboat Museum is no dry affair. In the preservation lab, a young woman answered questions while using a small hammer and dentists' instruments to dislodge sediment from a metal rope tie-down from the ship's deck. Evidence of the fragility of some recovered items was shown by two rolling pins. One had been properly preserved while the other had literally collapsed when it was accidently left out of the stabilizing chemicals for a short time.

In another area, a woman was enthusiastically showing youngsters - and oldsters - what life was like on the frontier. As her grinning "students" departed, she remarked, "I'm often the most excited person in the group!"

I don't believe I've ever been in a museum where I met someone who was directly involved in the discovery ... except for my stops at the Arabia museum. During both of my visits, Bob Hawley was there to talk about their adventure. The passion he feels for the museum and its contents is ever evident in the way he speaks.

Hawley said that when they began pulling the 200 tons of cargo from the steamboat, it was "like Christmas every day."

But even though the museum has been open nearly 20 years, he estimates they still have about 15 years of work left to sort, measure, identify and preserve what they discovered.

Today, the museum is mentioned as a must-see on virtually every Kansas City tourist site. That's quite a gift to the world from five guys just going to lunch!

Glass and metal ware (left) and shoes (middle) were among

the 200 tons of cargo recovered. Right, Art inspects saw blades.

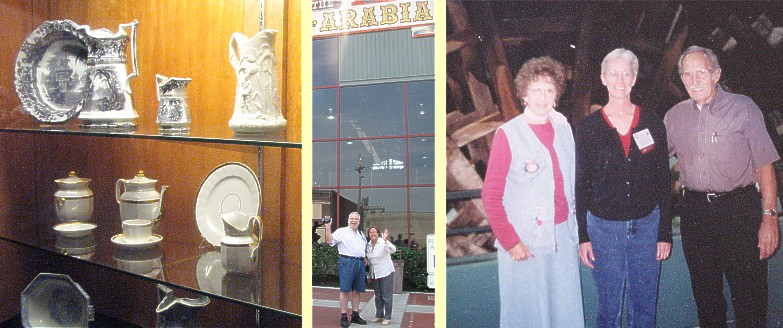

Left, fine china from the Arabia; middle, Art and Ingrid "mug" for the camera; right,

Bob's wife Florence, Gloria and Bob Hawley in front of one of the paddle wheels in 2003.