Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - Feb. 4, 2011

"The Dreamer Speaks Again"

The room was packed when my friends and I arrived. It was abuzz with lively conversation and laughter. People greeted each other warmly, and the good feelings were palpable.

But we hadn't come just to socialize. We were there to listen to a speech - a speech more than 7,000 people had gathered to listen to 43 years ago just a few hundred feet away in Ahearn Field House ... we were there to listen to a speech most people were certain would never be heard again.

On Jan. 19, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke at a K-State All-University Convocation. It was his last speech at a university before his assassination in Memphis less than three months later on April 4. In his jacket pocket, a hand-written note was discovered that contained several names: James McCain, the president of K-State at the time of King's speech; William Boyer, who was head of K-State's political science department and chairman of the All-University Convocation Committee that had invited King to campus; George Haley, a retired U.S. Ambassador to Gambia and brother of Roots author Alex Haley; and Homer Floyd, then the executive director of the Kansas Human Rights Commission.

On Dec. 13 of that year, a fire in Nichols Gym, the building that housed the offices of the university radio stations, destroyed the tape of Dr. King's address.

But last year, university archivist Tony Crawford received an audio copy of the speech from Galyn Vesey, the project director of Research on Black Wichita. In 1968, Vesey had obtained a reel-to-reel tape from Wichita radio station KFH that had broadcast King's lecture.

Haley, Floyd and Vesey joined us to listen to the tape. Boyer was also present via a video feed from his office at the University of Delaware. He had planned to attend, but a snowstorm in the East had made that impossible.

When the tape was started, the crowd quickly hushed. As Dr. King's words filled the room, we watched black and white photos of his visit on the large screens at the front of the room.

"We've come a long, long way, but we have a long, long way to go before we have a truly just society."

He cited favorable court decisions, including Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education, the landmark case that did away with the "separate but equal" idea he called "inherently unequal." He also mentioned the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the 1960s student sit-ins that called attention to the country's social problems and turned the country against the Vietnam War.

"This would be a good place to end my speech. It would be magnificent for a Baptist minister to do so."

"But if I did so, it wouldn't be the whole truth. It would be an illusion wrapped in superficiality."

He said problems for Negroes wouldn't end with stopping the physical abuse they suffered for there were other abuses - the kind that inflicted psychological and spiritual damage on them.

He pointed out that more than 30 percent of Negroes lived in sub-standard housing with - instead of wall-to-wall carpeting - "wall-to-wall rats and roaches." He spoke of a need for a Fair Housing bill in every state and how many high schools in African-American dominated areas provided only an eighth-grade education and were overcrowded.

"Even the language conspires to make the Negro feel like a nobody because of the color of his skin."

He noted there are 120 synonyms for black, including smut and dirt, whereas synonyms for white are words like noble and pure.

He condemned the "exaggerated use of the 'bootstrap philosophy'" - a reference to the notion that other peoples had come to this country and had lifted themselves up so why couldn't Negroes do the same? The difference, King said, was that those others were not brought here in chains against their will.

"It's a cruel gesture to say to a bootless man that he should lift himself up by his bootstraps."

But King remained convinced that non-violence was the way to help solve those problems, stating that violence created more social problems than it stopped, causing "an endless reign of meaningless chaos."

Although he was discouraged by what still had to be done to ensure equality, he said his hope was always renewed when he visited university campuses, where the student generation continued to work toward social justice.

Dan Lykins was one of those students. Today he is a member of the Kansas Board of Regents and was a participant in last week's event. He remarked how impressed he and his fellow students had been by King's speech.

I was only 14 when Dr. King spoke at K-State and was not present. But like Lykins, listening to the tape, I was moved by his eloquence and passion. Boyer probably captured my feelings best:

"As he spoke, I became mesmerized by the power and eloquence of his riveting message, the lifting and cadence of his transforming voice, and the passion and meaning of his words. It was as if I was being swept by the sheer greatness of his presence, such as I have never before or since experienced."

But in the end, I felt some of King's opening words, now 43 years old, are still the most fitting:

"We've come a long, long way, but we have a long, long way to go before we have a truly just society."

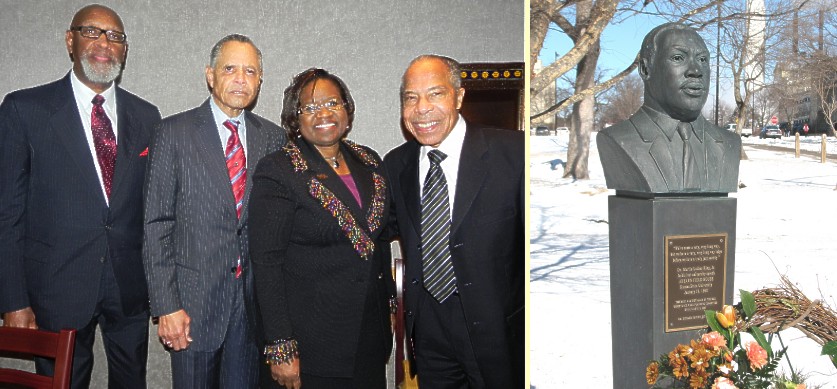

Left: friend Pat Hudgins, third from left, and I attended the Martin Luther King, Jr. Luncheon.

Pat later interviewed, from left, Galyn Vesey, project director,

Research on Black Wichita;

Homer Floyd, retired executive director, Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission;

and George Haley, retired Kansas State Senator and former U.S. Ambassador to Gambia.

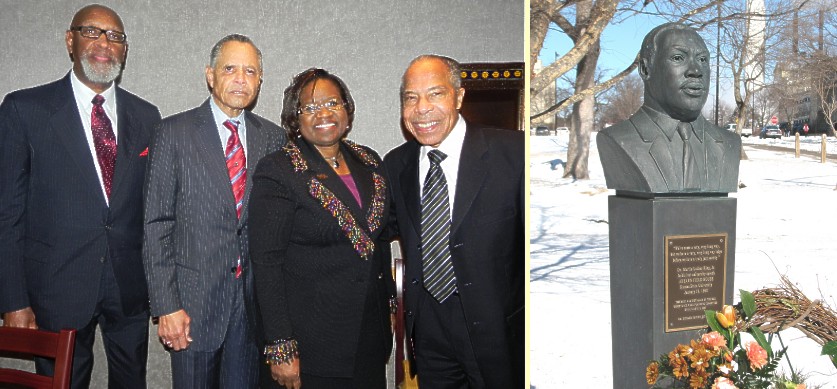

Right: bust of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the east side of Ahearn Field House.