Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - Jan. 21, 2011

The Goodnow House

Most of my students will spend the majority of their career concentrating on what is changing in the world - what is new. But as a journalism professor, I try to encourage them to be mindful of how things today are built on the foundation of yesterday.

As part of that effort, two years ago I asked Cheryl Collins, director of the Riley County Historical Museum, to speak to my News and Feature Writing class and to give us a tour.

Then, almost as an afterthought, I asked if she would also take us through the Goodnow House next to the museum.

I had driven by the small two-story stone house hundreds of times since I came to Manhattan in 1971, but had never been inside. Its builder, Isaac Goodnow, was born in Vermont on Jan. 17, 1814. After marrying Ellen Denison, he settled into a teaching position in the East. But after listening to a rousing anti-slavery speech in 1854, he decided the couple should move to Kansas. His goal was to help the cause of the free-staters and to improve Ellen's health by moving to a warmer, drier climate. He and a bunch of politically like-minded folks headed west the following March.

A man of substantial energy, Goodnow became a Kansas legislator, was a railroad promoter and was the first elected state Superintendent of Public Instruction. But for Manhattanites, Goodnow is most remembered as a co-founder of both the city and Bluemont Central College - which became Kansas State University.

The Goodnows did not have children to provide later generations with insights into what was happening during those tumultuous times and the years that followed. But Isaac left a collection of diaries that offers a good window into the past.

And their home, which was built in 1861, allows us to get some idea of how an important pioneer family of the state lived.

The day we visited, the interior was furnished with family belongings that were characteristic of domestic life in the late 1800s. But the home is now empty as it undergoes interior renovations. It is expected to be re-opened sometime this year - the 150th anniversary of Kansas becoming a state and the beginning of the Civil War.

The original home was made from native Kansas limestone and had two rooms - one downstairs and one over it. An addition on the north side was made in 1868, a barn was added to the property in 1869, and a bedroom was appended to the east side of the house in the 1870s. And as with any home today, renovations occurred, such as the addition of a fireplace in 1909.

I asked Collins how one accurately refurbishes a home that changed substantially during the time the Goodnows lived there and afterwards. She said the process has been a painstaking one. First, workers carefully removed wallpaper and paint from walls, ceilings and floors to determine how the house was originally built.

"A lot of clues came out," she said.

Workers discovered that traditional methods, such as putting plaster directly onto stone, were used. Some upstairs floors had been painted, and every effort was made to match the palette as closely as possible. To "document" part of the home's history, they left a small patch in one room where the most recent paint layer and all the previous ones are exposed.

The wallpaper is also being replaced with paper that has designs that were common during the period the Goodnows lived there.

"We did find a notation (in his diary) about wallpaper for the parlor, so we used that information to guide us in selection," Collins said.

But she said they had to rely on the house itself to do quite a bit of the "talking."

"We found where original chimneys were and thus where the stoves were located, evidence of where shelves or hooks had been hung and all sorts of interesting details like that," she said.

Native black walnut woodwork, built-in cupboards and closets, and a chimney that wraps around an exterior window are among some of the unusual features of the house.

Another oddity is the iron fence on the east side of the house. It was made with rounded tops. Collins said a story that has been passed down is that Ellen Goodnow insisted on the rounded tops so horses wouldn't hurt themselves if they jumped over the fence.

When the home was built, Manhattan was a small community a mile or so to the southeast. Its location supports another story to the effect that Ellen used to watch from the south window on the upper floor for Isaac's return from the town and other points east.

I find many other details interesting, such as after the Goodnows died, the house passed to Hattie Parkerson, a niece whom they had adopted. Eventually the home and many of the Goodnow belongings were donated to the Kansas Historical Society.

But sites such as the Goodnow House and the thousands of others sprinkled across the country and world play a role more important than just preserving the heritage of one man or family or group. As a teacher, I am well aware that we learn in a variety of ways. Reading is one way and it is a good one for conveying details and the order of events. But to look out over Omaha Beach in Normandy, to walk through the Old North Church in Boston or even to stand in the small limestone house of Isaac and Ellen Goodnow is to acquire an understanding of how things were in a way that words have trouble matching.

So walls too can speak. And if we listen, they can say quite a bit.

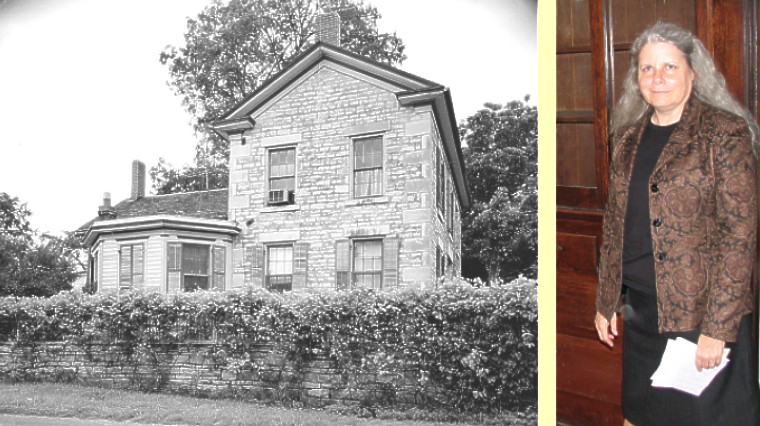

Left, Goodnow House in a 1958 National Park Service photo; right, Riley County

Historical Museum director Cheryl Collins inside the Goodnow home.

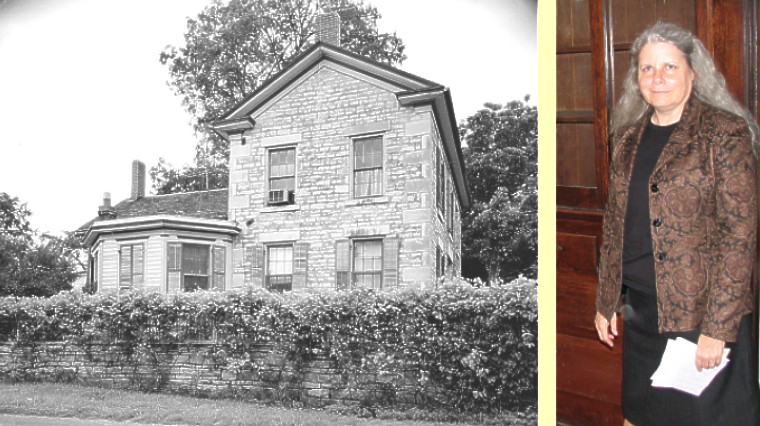

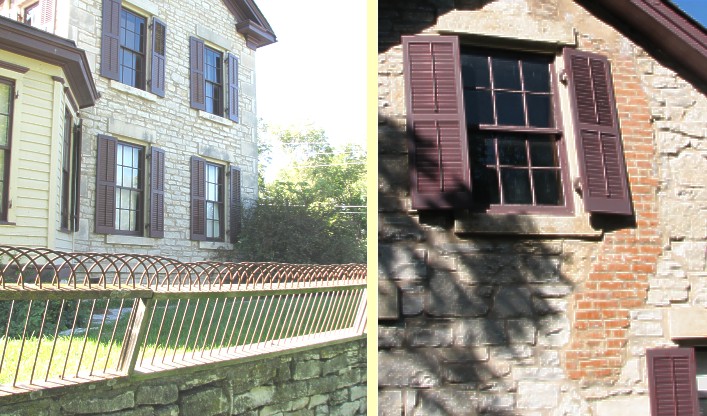

Left, the unusual rounded tops of the property fencing;

right, red bricks fill the space created by the removal of a chimney flue.