Preview

By any measure, Morganville, Kansas seems a long way from the busy outside world. Only occasional prairie winds and the

infrequent trucks hauling crops to or from the local elevator interrupt the stillness. Beyond its few blocks that are

home to less than 200 citizens are fields that stretch for miles. They annually produce tons of grain sorghum, soybeans

and wheat.

Things were different near the end of the 19th century. The landscape was dotted by small family farms. These

settlers needed the stores and services provided by the "live little town," as the now long-gone Morganville Tribune

newspaper called the village.

But mechanization led to a merging of these small holdings into large farms. As the years passed, the number of

families on the land decreased and transportation became better. The goods and services needed by those who remained were

increasingly provided by merchants in Clay Center 10 miles to the southeast.

In 1939, fictional Kansas youngster Dorothy from "The Wizard of Oz" became famous. But no one would have guessed that soon

tiny Morganville would also become known to much of the world.

By the end of World War II, people across America had seen the newspaper pictures and heard stories from their returning

servicemen about the destruction caused by the fighting. But many people were not satisfied to donate money or clothing to

a charity without knowing what became of it.

Morganville water tower on the community's east edge

Adopting a war-damaged town seemed to be a better idea. People could then see their efforts take effect and adjust what was sent to

match specific needs.

Morganville adopted Fèves (pronounced fev) in far-away France. But after the initial excitement of selecting the French

village, doubts arose. Morganville was Protestant and Fèves was Catholic. Today, that difference

seems unimportant. But the friction between the two major divisions in Christendom was strong then. Intermarriage between

couples of these different faiths was comparatively rare. Another indication how strong those feelings were, can be heard in a

statement made by Morganville writer Velma Carson. Noting how much things had changed in the village by 1954, she said,

"This year, we've got a Catholic girl teaching Home Economics at school."

Another problem was alcohol. Morganville was in "dry" Kansas, but the inhabitants of Fèves drank wine and made a

potent brandy from a local plum. This was no small difference. As late as the 1970s, Kansas threatened to file lawsuits against

airlines that served alcoholic drinks to passengers while flying over the state.

But children, such as Liliane Dorrwachter and Gabrielle Gaspard, saved the day. When the people of Morganville

heard that the children of Fèves were hungry and had no milk, the second-guessing stopped. They needed to take care of

the children!

The village's efforts to help those devastated by World War II brought attention, both because the village was so small

and because its citizens produced a pageant, including an original play, to raise money.

Fèves children Liliane, left, and Gabrielle

The efforts of the Morganville people had a great impact not just in Fèves, but across the United States.

Morganville's success encouraged much larger cities to also adopt war-torn sisters. Peter Wyden, a journalist with

the Wichita (Kansas) Eagle newspaper, was just beginning his highly successful career when he visited Morganville. His story

and others led Wichita to adopt Orléans, France, a relationship that has continued to the present.

Elmore McKee, a minister with an international reputation, included the tale in a series of radio programs he wrote.

Satellite view of Morganville. Grain storage bins are on the left. The southeast-to-northwest paths of the long-gone rails can be seen at the left.

"A Prairie Noel" was broadcast across the United States two days before Christmas in 1950 on the NBC radio network

and to U.S. servicemen overseas on the Armed Forces Radio Service. A longer version appeared in McKee's seven-edition book,

"The People Act," which was first published in 1955.

Yet, as time passed, the story faded, except in the memories of a few older citizens in Morganville and Fèves.

In the fall of 2012, Gloria Freeland, a professor in the A. Q. Miller School of Journalism and Mass Communications

at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas, became acquainted with the university's Chapman Center for Rural

Studies. One of the center's aims is to preserve the history of the state's small rural communities. Freeland, always looking

for real-world experiences for the fledgling journalists in her classes, saw this as an opportunity. In the spring

semester of 2013, she assigned students the task of writing articles about 10 small Clay County communities. Those stories

were completed in May.

Gloria Freeland

The Clay Center Dispatch, Clay County's local newspaper, wished to publish the articles, confident its readers would enjoy learning more about the area's history. But with the decision to go public, Freeland wanted to guard against the beginners' mistakes budding journalists frequently make. So she asked her husband Art Vaughan to fact-check and edit them.

In the spring of 2013, students Logan Falletti (left), Mariah Rietbrock (center) and Katie Good researched and wrote the Morganville story for Freeland's News and Feature Writing class.

All the articles were interesting because of the important role each community played in the lives of the people who lived in them or nearby. But the Morganville story, born of the collision of world events which culminated in World War II, was unique. The small community had literally reached out and touched the world.

The students' work, combined with Vaughan's efforts to verify story details, led to a reconnection of the villages 65 years

later. A reception after Christmas 2013 in Morganville for two aid recipients from her French sister village was followed

by reception for Freeland and Vaughan in Fèves the following spring. In 2015, the small farming community in America's

heartland hosted 20 citizens of its once war-devastated sister. In the fall of 2016, the mayor of Morganville and his wife

flew to France and met with the mayor and citizens of Fèves. And in June 2019, 11 Americans, including two who were in the

1948 play, were designated "VIPs" at a reception and dinner for them in the little Lorraine village.

Art Vaughan

This book was created to preserve this unique story, a story that may never have been, were it not for the hungry Fèves children.

Cover child Gabrielle married Maurice Neveux, one of the schoolboys of Fèves when Morganville was sending aid. Grandparents

Gabrielle and Maurice died in 2011. Cover companion Liliane married Pierre Lagrange and they live in a suburb of nearby Metz. They enjoy

time with their children and granchildren. Others who were youngsters in 1948 are met later in the book.

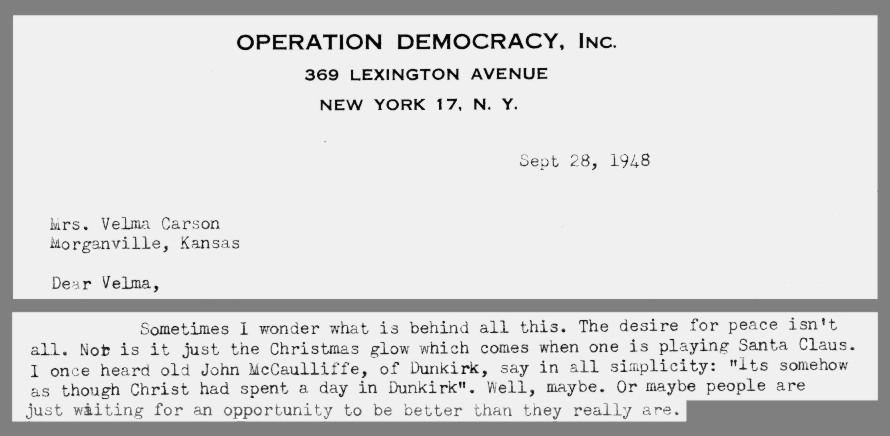

The book's title arose from a letter Charles Todd, a key figure in connecting Morganville with Fèves, wrote to Velma Carson, the

play's scripwriter. His surprise in the strong national attention these pairings received prompted him to wonder if "people are

just waiting for an opportunity to be better."

Portions of a letter sent by Operation Democracy's Charles Todd show the origin of the story's title.

The French flag and the flag of the United States both use the colors red, white and blue, so layout designer Katherine

Vaughan felt they were a natural choice for the cover.

From left-to-right are the flags of the United States, Kansas, the village of Fèves, Lorraine and France. Just as Morganville is in the state of Kansas, Fèves was in the administrative district of Lorraine.