After spending the 1914-1915 school year teaching at the Wheeler country school not far from her home, Carson enrolled at what was then called Kansas State Agricultural College (KSAC), later Kansas State College (KSC) and today Kansas State University (KSU), in nearby Manhattan. The school annuals reveal Carson to be a very busy person. But more than just having full days, her interest in literary subjects, women's issues and social matters is evident.

Velma Lenore Carson

- Degree - Journalism

- Theta Sigma Phi - Journalism society

- Ionian - Women's literary society

- Quill - Writing

- Purple Masque - Drama

- Junior Farce - Drama (chairman)

- Oratorical Board - Speech contest

- Royal Purple - Yearbook (editor)

- Collegian - Newspaper reporter

- Cosmopolitan - Women working for peace

- Y.W.C.A. - Empowering women, eliminating racism

- Y.W.C.A. Cabinet - YWCA governing board

- Prix - Leadership honorary

- Xix - Outstanding women honorary

- Class President - Head of her class

- W.A.A. - Women's noncompetitive athletics

Carson during college years

When Carson was young, the great migration from farms to

cities had already begun. But while the men of these families now worked in shops, businesses and factories, their

wives were still expected to be homemakers. On the farm, women had vegetable gardens to supply fresh produce for the

family. To make certain these skills were acquired by the college's young women, KSAC required them to take a class

called "Kitchen Gardening." (It was not done in the kitchen, but to provide produce for the kitchen.)

The 1909/1910 KSAC publication, "The Industrialist," described the course as follows:

Kitchen Gardening. Junior year, spring term. Class work, two hours. Two credits: Lectures on the essentials

for home-grown vegetables, plants, soils, fertilizers, seeds, planting, cultivation, and the requirements of

various groups of species.

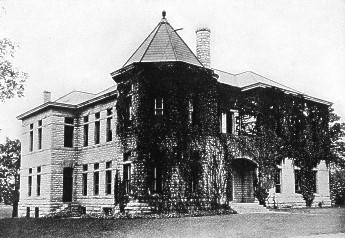

Kedzie Hall in 1916 looking to the southwest;

Carson's journalism classes were taught here.

Carson did not take the required Kitchen Gardening course, enrolling in music appreciation instead. Perhaps she felt it was a waste

of time for a farmer's daughter to enroll in such a course. As a consequence, she left KSAC without her degree.

But the lack of a diploma did not keep her from experiencing an interesting life.

- Sings at Ft. Riley for WWI soldiers

- Newspaper woman in Kansas City; writer in Chicago

- Marries KSAC class president/engineer Homer Cross

- Writer in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania

- Writer in Greenwich Village, New York

- Meets famous actors, musicians, poets, has radio show

- Meets Margaret Sanger, distributes birth control materials

- Meets A. Philip Randolph, helps unionize Pullman porters

- Daughter Cynthia born (1928)

- Divorced from Cross; marries painter Leonard Rennie

- Works in Washington, D.C.

In 1945, Carson, who always used her maiden name,

returned to Morganville to visit her parents while second husband Rennie was away on a "project." It appears the

project was another woman and Carson learned in a letter from him that he was divorcing her.

Carson and her daughter Cynthia - who also used Carson as her last name - lived with Carson's parents in the home they

had bought in Morganville after they retired. The farm was turned over to Lloyd. Cynthia finished high school

and then enrolled in the Kansas State Teachers College, now Emporia State University, in Emporia, Kansas.

This was almost certainly a difficult time for Carson. After living in the largest cities on the East Coast,

Morganville didn't offer many diversions. Her parents were old, and then, in 1947, her father died. In conservative

Republican Kansas, people who had traveled, lived in large Eastern cities, voted Democrat and were twice-divorced, were

thought to be just one step away from being Communists.

Perhaps the most difficult thing for Carson to deal with was her cataracts. She needed a strong light, preferably

the morning sun, to read or write.

Yet despite her strong-willed ways and a political outlook that seemed completely foreign to many of her neighbors,

something about Carson allowed her to motivate others - a sort of won't-take-no-for-an-answer attitude.

By late 1947, the pieces were in place. Eisenhower's support of UNESCO prompted people across the state to think beyond

their horizon. Millikan was prodding the citizens of the little village where he was the minister to do something tangible.

Todd's hometown experiment provided evidence that even small places can have a big impact. Carson combined these three

elements, prompting Morganville to do something extraordinary.