In May of 1946, at the age of 35, Todd was discharged from

the Army and accepted a position as publicity director with American Aid to France. He suggested to the city

fathers in his hometown of Dunkirk, population 18,000, that their French partner could use some help.

He never anticipated what would happen! All parts of the town became involved, culminating in a city-wide effort on

November 28 - Thanksgiving Day.

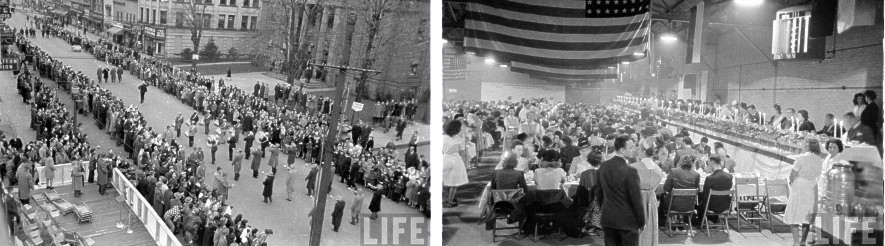

LIFE magazine photos of the Dunkirk-to-Dunkerque Day celebration

The French ambassador Henri Bonnet, as well as French actor Charles Boyer and French actress Simone Simon,

joined the effort.

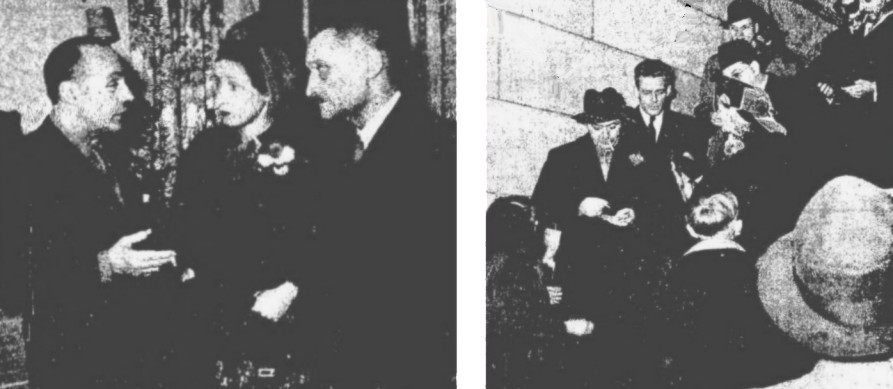

Left: Actor Charles Boyer chats with French ambassador Henri Bonnet and his wife; right: Boyer indulges an autograph seeker after leaving the Dunkirk High School. Todd is immediately behind Boyer.

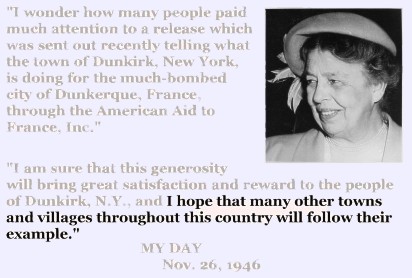

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about the

Dunkirk relief effort in her syndicated column "My Day" that was read by more than four million Americans every day.

As if things weren't bad enough in Europe, the weather at the start

of 1947 was especially severe. The warm moist winds that accompany the Atlantic Gulf Stream normally give Europe

and Britain mild wet winters.

But in late January of 1947, a high-pressure area settled over Scandinavia which brought strong cold winds from

the east. It caused the warm moist Gulf winds to split as they approached Europe. Britain and northern Europe

experienced extreme cold and heavy snow. Southern Europe received triple its usual rainfall.

Top: Normal winter with warm moist winds;

Bottom: 1947 winter with cold eastern winds

Winter sports, such as ice skating on Britain's Thames River, were popular

as a way to stay warm because coal was often in short supply.

Reports of the weather conditions in Europe reached America, increasing a feeling that something had to be done

and it had to be done quickly.

Drew Pearson was the most widely-read columnist in the United States. While it wasn't his idea, his support to create a

"Friendship Train" appealed to Americans.

Left: London double decker bus buried in snow; right: bicycling on the Thames River

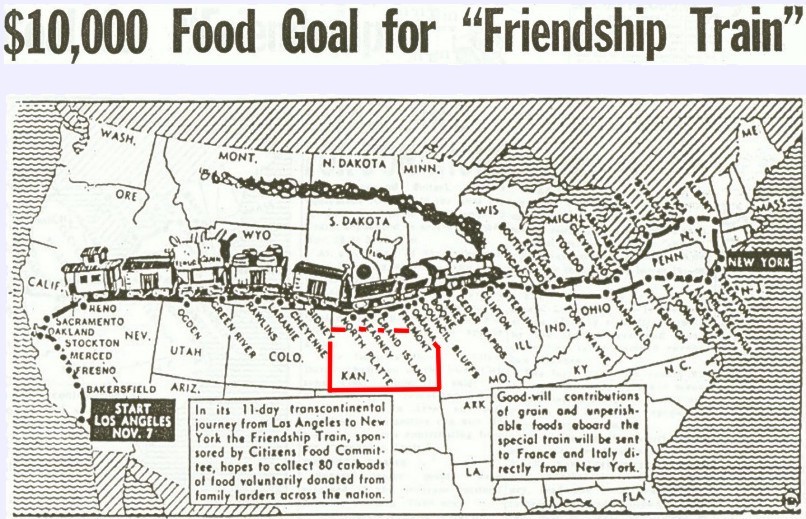

The goal of the Friendship Train was to collect

80 railroad boxcars of food, clothing and other articles. It would start in California and travel across the country, stopping

in major cities to collect donations. When it reached New York City, those cars would be loaded aboard a ship bound for

France or Italy.

Train route, published in the Ames (Iowa) Daily Tribune, November 7, 1947. Kansas border (red) added

Response from Americans was much greater than

anticipated. By the time the train reached New York City, the hoped-for 80 cars had grown to 700 cars!

News of Dunkirk and the Friendship Train prompted Americans into action.

Locust Valley, New York had the highest per-capita wealth in the United States at that time. Important people

called it home. Augustin "Gus" Hart lived there, and he had been a paratrooper on D-Day. He had seen the destruction at

Sainte-Mère-Église. He suggested to his neighbors that they should do for it what Dunkirk, New York had done for Dunkerque,

France.

The Locust Valley effort took shape in 1947 and was called "Operation Democracy." The enthusiasm for Hart's suggestion

gained publicity for "town affiliations." Initially, Todd was asked for advice, but he soon left AAtF to become O.D.'s

day-to-day leader and grow it into a national organization.

Columnist Drew Pearson, Friendship Train supporter

Operation Democracy's shipments were handled by American Aid to France. Packages carried a label with these words:

All races and creeds make up the vast melting pot of America, and

in a democratic and Christian spirit of good will toward men, we, the American people, have worked together to

bring this food to your doorsteps, hoping that it will tide you over until your own fields are again rich and

abundant with crops.

Augustin "Gus" Hart

Location of Locust Valley

and Sainte-Mère-Église