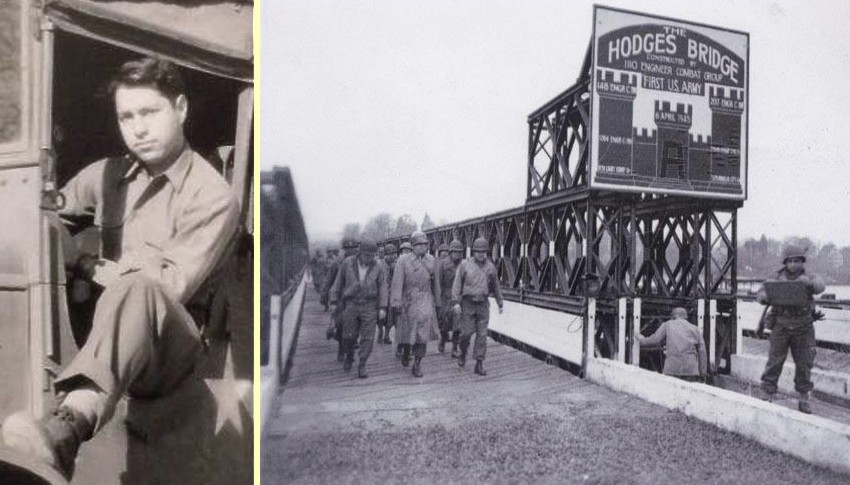

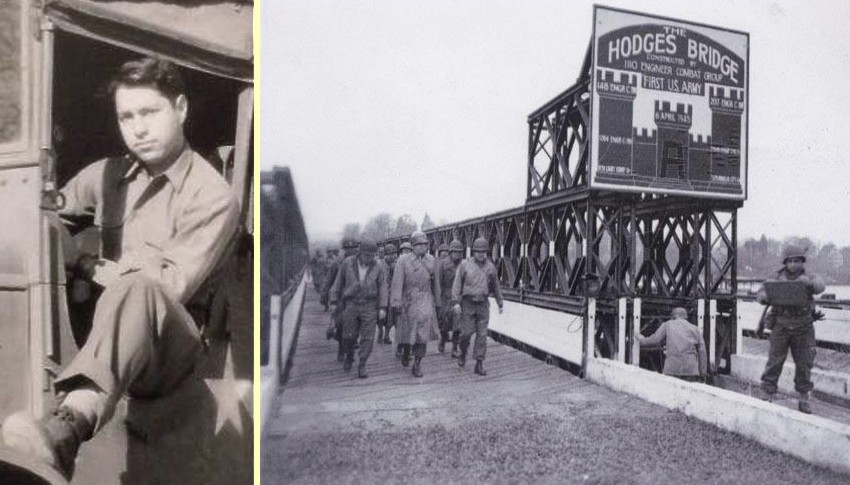

Left: Master Sergeant Kruh; right:opening ceremony on Hodge's Bridge

WWII Snapshots by Mark Stephan - 2008

Robert Kruh, Army

As a young man growing up on a farm just outside of Lebanon, Ill., Robert Kruh hadn't a care in the world. But on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941,

that all changed. Kruh was sitting in his home relaxing and listening to the radio, when the news hit.

"The Japanese have just bombed Pearl Harbor!"

Kruh said he had a blank reaction to the news at first. As the day progressed, he realized that America was under attack. He had no

understanding of the Japanese motive, but believed that something needed to be done, and it needed to be done fast. He was only 16,

however, so could not yet join the military. He spent the next two years attending college. In fall 1943, Kruh enlisted in the Army.

"It was either join or be drafted," he said. I got on a train and I made my way down to St. Louis. When I got there, I went to the

military draft office to sign up and did just that," Kruh said.

Almost immediately, Kruh went to Camp Grant in Illinois, where he and the other men learned basic mathematics as well as engineering

calculus formulas to help with the placement of bridges throughout the European terrain. From there, Kruh went to Fort Benning in

Columbus, Ga.

"At Fort Benning, I was put through basic infantry training. At the completion of training I was assigned to the 102nd Division of

the 405 Infantry," Kruh said.

After his assignment, Kruh moved to finish his training in Dayton, Ohio, where he spent four months learning engineering. The

engineering would later play a role in one of Kruh's most memorable military experiences.

When Kruh's engineering training ended, his infantry unit moved to Camp Swift in Texas to learn skirmishing techniques and further

their combat training. Skirmishing is the act of clearing surrounding areas of enemy combatants for military advancement. At the

completion of his skirmishing training, Kruh was transferred to the 1264th Combat Battalion. Kruh claims the transfer saved his life.

"When I was I transferred to the battalion, I did not think much of it," he said. "However, it meant much more after the war. I found

out when the war was over that there were only seven survivors of the combat infantry unit that I was originally assigned to; the

rest had been casualties of the war."

Soon after the transfer, Kruh and the rest of the men that he had met while joining the 1264th would put all of their training to

use building tank traps and bridges to keep the Army moving.

In fall 1944, Kruh and the rest of the battalion shipped out. Following D-Day - June 6, 1944 - there was still much to do in Europe

to aid the war. Kruh and the rest of the battalion left from New York in a massive convoy of ships. It was the largest convoy of the

war to cross from the United States to Europe.

"The convoy was so large that I could not look out the sides of the ships without seeing boats for miles. It was funny, the convoy

was so large that I actually had to ask my superior what kind of ships were on the outside of the convoy because I could not see the

outskirts," Kruh said.

It took them 11 days to make it to Portsmouth, England. Immediately upon arrival, the men went to the Cherbourg Peninsula near

Normandy in France. The men of the battalion sat on the beach and removed mines that were threatening the Allied forces. After a

week, the men moved on through France to Belgium.

Toward the end of 1944 and the beginning of 1945, Kruh and the rest of the men caught up with General Omar Bradley and his troops.

Bradley had just taken command of the 12th Army group that consisted of 21 divisions and 903,000 men.

The goal for the men was to clear the mines that enemy troops had laid and to set tank traps. The reason for these activities was

to ensure the safety of the Army trucks trying to get supplies and food to the troops that were in need. Clearing mines, however,

was not always the easiest job for a military man.

"During the war, we always carried M1 rifles," Kruh said. "It was required, but we never used them. Any casualties that we experienced

were not from rifles but from men stepping on box mines. No one I knew personally, but, nonetheless, good men were dying, and it was

not even from enemy fire."

As January 1945 approached, the men started to see light at the end of the tunnel, he said. A mine-free path had been cleared,

allowing the men to pack up camp to move through Belgium and into Germany. Once in Germany, Kruh and the rest of the engineering

battalion would get their chance to prove what they were made of and make their mark in the war.

During the war, the biggest obstacle was not enemy fire or even the mines, Kruh said. It was the Rhine River. The Germans had blown

up almost every road or bridge that was accessed from the west bank of the Rhine to the east bank, Kruh said. They demolished these

passages so that the U.S. military would have no way for advancement. The Germans underestimated the tenacity and will of the 1264th

Combat Battalion.

But building a bridge across the Rhine proved to be difficult for the 1264th Combat battalion engineers. It would require ingenuity.

The men would have to use what they had on hand to build this bridge that would help get the Allies across the Rhine to defeat the

Germans. They would have to build a bridge large enough and sturdy enough that it would be able to hold tanks.

Normally, the men would have used pontoon boats that would be anchored using cable and ties to the shore. But pontoons were not

sufficient to carry the incredible weight of a loaded tank. So the engineers had to put their minds together and come up with a

better plan. The men would have to use local river barges to form their bridge. Not only would they need many barges but many men

to help with the fabrication.

"The bridge building required a lot of man power; I'd say thousands of men were brought in to help put that monster together," Kruh

said.

The bridge took just five days to build across the 1,400-foot Rhine River. The men sank heavy barges up-river and attached cables to

them. Once the cables were secured, the men attached them to floating barges that sat about 100 yards down river. The floating

barges acted as the base for the bridge.

The men used prefabricated joints and wood planks to lay across as the floor for the bridge. Kruh said the prefabricated material

for the bridges became known as Bailey Bridges because the idea for prefabricated bridges for military use came from British engineer

Donald Bailey. Kruh and the rest of the men had all parts of the bridge together and ready by the middle of March.

Bradley was in command of the whole project and Gen. Courtney Hicks Hodges served closely under Bradley and was in command of the

first unit to cross the bridge. Thus the bridge was dubbed Hodge's Bridge. As soon as Bradley cut the ribbon for the ceremony, the

first tank immediately crossed the bridge to catch up to the Germans. Kruh followed in the supply truck that he drove at the time.

The supplies were for the U.S. troops that were already on the west bank. The bridge stood for one year and served to transport

supplies to France and the rest of Europe. It was knocked down during the reconstruction of Bonn and other German cities that had

been destroyed by the war.

Soon after the construction of the bridge, the war was coming to an end. Kruh, however, was not done yet.

"The day that Europe was liberated, I was told that I was going to go to Japan," Kruh said. "Luckily, I never made it because Japan

was liberated before I even had a chance to think about leaving."

A point system was used to see who would be allowed to go home at certain times and who would stay. Kruh had enough points to go

home almost immediately, but stayed because other men had wives and children that they had not seen in years. So Kruh stayed another

nine months to help with the clean up of German cities that were destroyed.

While in Germany, Kruh spent most of his time clearing rubble out of Frankfurt. In Frankfurt, Kruh and the rest of the men occupied

various office buildings and houses that still stood.

After three years of driving supply trucks, building one huge bridge, and cleaning up the rubble in Germany, Kruh returned home to

the United States and used the G.I. bill to further his education.

"The G.I. Bill was money that the government gave to men returning from World War II to attend college and get an education," Kruh said. �They also paid us one year of unemployment payment so that we could secure a decent job.�

He attended Washington University in St. Louis, Mo. While attending Washington, Kruh met the two loves of his life: his wife Jan and

what he described as "the wonderful world of chemistry."

"After the war, the second best thing of my life happened," he said. "The first best thing was that I was transferred and was not a

casualty of war and the second was when I met my wife [Janet Jackson]."

During college and after, Kruh stayed in the Army reserves for another nine years. In the reserves, Kruh was not very active. He said

he would occasionally have to check in at headquarters, but most of his time was spent at school. The military even called to send

him to Korea, but because he was in college at the time, his service was waived.

After receiving his undergraduate degree in chemistry, Kruh eventually obtained his doctorate in chemistry. He became a professor of

chemistry at Kansas State University. Although he retired from K-State, he still has an office on campus as professor emeritus for

the chemistry department. Kruh works with the Department of Continuing Education at Kansas State helping students find a path that

works for them after their undergraduate degree.

But Kruh has not left his Army memories behind.

"Just the other day, I was thinking about my days in the war," Kruh said. "I started thinking that the military really provided me

with a strong work ethic and helped me to be a stronger man in my life - not to mention I can still fit into my military jacket."

Left: Master Sergeant Kruh; right:opening ceremony on Hodge's Bridge