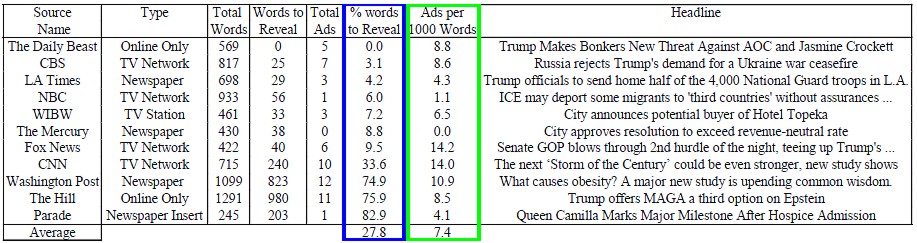

Art's online-news research results (chart by Art)

Source Name - Public name of the news purveyor

Type - Nature of the purveyor's primary business

Total Words - Number of words from the start of the headline through the article conclusion

Words to Reveal - Words from first headline word to the point where the core information is revealed

Total Ads - Number of ads internal to the Total Words text

% words to Reveal - Words to Reveal divided by Total Words expressed as a percentage

Ads per 1000 Words - Number of ads for a 1,000-word item if ads were placed at the same rate throughout

For a reader, a quick reveal - that pyramid thing - is better, i.e., a small number in the blue column. These results were used to

order the samples - best on top; poorest on the bottom.

Ads pay the bills on free sites such as these, but more information per ad is better for the reader, so a smaller number in the

green column is also desirable. Since my weekly column target is 1,000 words, the green column is how many ads would break up

my column in that particular purveyor’s publication. They range from a low of none to a high of about 14!

It might be concluded that as the number in the green column rises, the purveyor is less and less about delivering news supported

by advertising and is more and more about delivering advertising using news as bait.

Any publication that can get to the main point in less than 10 percent of its length is doing a good job in the inverted pyramid

matter. One managed to do it in the headline. But what is a passing grade in advertising density is probably a matter of reader

tolerance.

I was startled to see that the once-venerated Washington Post required reading 75 percent of the text to get the main idea, while

delivering a high density of ads. Owner Jeff Bezos declared in a staff memo, "We are going to be writing every day in support and

defense of two pillars: personal liberties and free markets." Bezos, who also owns Amazon, appears to have shifted the paper's

emphasis from news to commerce.

As a columnist, I am supposed to deliver a grand conclusion at this point, but practices such as sprinkling ads within news items

was alive and well in the 19th century. Using a headline to draw attention is also old news. So, much as it has always been, the

burden remains on the reader to separate the facts from the filler.

Comments? [email protected].

Other columns from this year may be found at: Current year Index.

Links to previous years are on the home page: Home