Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - May 24, 2024

"Tags of Honor" revisited

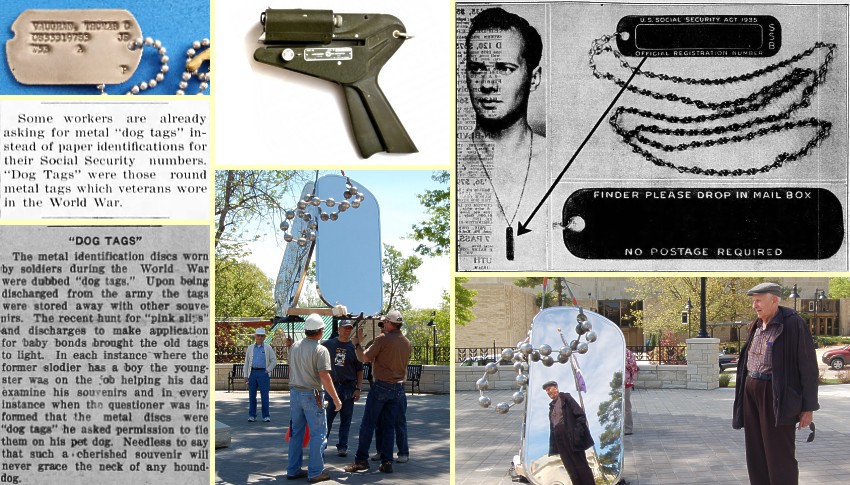

While cleaning recently, I came across my brother-in-law's military identification "dog" tags. Husband Art's brother Tommy, who

died three years ago, had served in the Army during the Korean War.

While I knew the tags included a service member's name and ID number, I wondered what the other items meant. With Monday being

Memorial Day, it seemed an appropriate time to find out.

I learned the "T-53" meant Tommy had received a tetanus shot in 1953, the "A" was his blood type, and the "P" was for Protestant

- his religious preference.

While my questions had been answered, I decided to dig a bit deeper.

The origin of the common term "dog tags" in reference to these identification badges worn by military personnel is unclear.

Wikipedia suggests, without evidence, it arises from similar items used to identify pets.

Another popular origin story involves John Hamilton, the head of Republican Party during the 1936 presidential campaign. Waving a

chain containing a rectangular tab of metal at a Boston gathering, he claimed it was one of the new identification tags U.S.

workers would have to wear if the Social Security program went into effect. Since Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt won in a landslide

that November, Hamilton's suggestion that Roosevelt would treat people like dogs hadn't proved effective.

Another origin tale involves World War II draftees claiming they were treated like dogs. This story ignores the fact that the term

"dog tag" was widely used to refer to the ID discs worn by soldiers during World War I.

The notch in one end of the tags used in World War II is the source of another myth. It asserts that when a service member was

killed, a comrade inserted one tag into the mouth of the dead man with the notch helping wedge it between the two front teeth of

the victim. The other tag was then given to an officer to begin the process of documenting the death.

While false, there is an element of truth in it. The information on the tag was in raised letters such as those sometimes seen on

credit cards. A tag from the dead man was inserted into a slot in a small hand-held gun-shaped device. The reporting form was then

inserted below the tag. When the handle was squeezed, the tag was pressed onto the form. A ribbon located between the two, much

like that between the keys and paper in a typewriter, produced a printed copy of the tag's text. The off-center notch ensured the

tag was inserted with the proper orientation.

However, the imprinter was susceptible to battlefield grit and grime, making its functioning problematic. Furthermore, there was a

concern that its gun shape might cause an enemy soldier to assume the user was not a medical corpsman, but an officer - a

highly-preferred target. These problems discouraged the use of the imprinter.

Regardless of what they were called, military identification badges were in use as early as the Roman empire. But during the

American Civil War, none were provided. Soldiers concerned about being buried in unmarked graves used a variety of ways to identify

themselves. Pinning a slip of paper with their name inside their clothing was common. Others carried objects, such as coins, that

had their names scratched on them.

This fear of dying anonymously was justified. Of the 325,000 Union soldiers buried in national cemeteries, 149,000 were listed as

"unknowns." The number of Confederates in this category is thought to be even greater.

By World War I, all U.S. service members were required to have identification tags and despite technological advances, such as DNA

matching, they are still issued today. But they have changed in various ways over the years. For a 40-year period, a soldier's

Social Security Number was used for identification. This was stopped due to concerns over identity theft. Friend Deb, whose husband

Chuck served in the Vietnam War, mentioned another. He told her rubber bands were wrapped around their tags so they wouldn't make

noise when soldiers were trying to sneak up on the enemy.

While these small pieces of metal are likely to be given little thought in any reflection on our country's wars, they are the focus

of Kansas State University's World War II Memorial. Titled "Tags of Honor," it features a striking sculpture of two large polished

metal plates leaning on one another and connected by a beaded chain. These larger-than-life dog tags were designed so when students

and others look at them, they see their own faces, encouraging reflecting on the impact the war had on the campus.

To assure accuracy, the artist used as a model the tags borrowed from K-State alumnus John Lindholm, a 1949 graduate and veteran of

World War II. Lindholm, who was later an engineering professor at K-State, also happened to be Art's boss for a time. In a second

small-world twist, Lindholm was stationed at the same airfield in England as Art's uncle Pete. Both were B-17 pilots.

I imagine Tommy kept his dog tags as a mere memento of his military service and well may have never thought of them again. Yet 70

years later, their discovery prompted me to look into their history.