Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - July 28, 2023

My own national park

It doesn't seem that long ago that I planted beds of irises, peonies and day lilies, all selected from those that grew on our

family farm. I then augmented their blooms with those generated by annuals, such as marigolds, nasturtiums, petunias, geraniums,

zinnias, and chrysanthemums. I also tended a few pots of tomatoes and peppers to provide a few fresh vegetables for our table.

Every spring and summer, I looked forward to going to local nurseries to pick out seeds and seedlings, but that pretty well ended

in 2011 when I suffered a herniated disc in my back. By doing physical therapy and being careful, I avoided surgery, but I decided

not to tempt fate. I turned over mowing, trimming and planting to others.

That didn't mean I lost interest, however. I'm much like my mother, who was always excited to look at gardening catalogues and

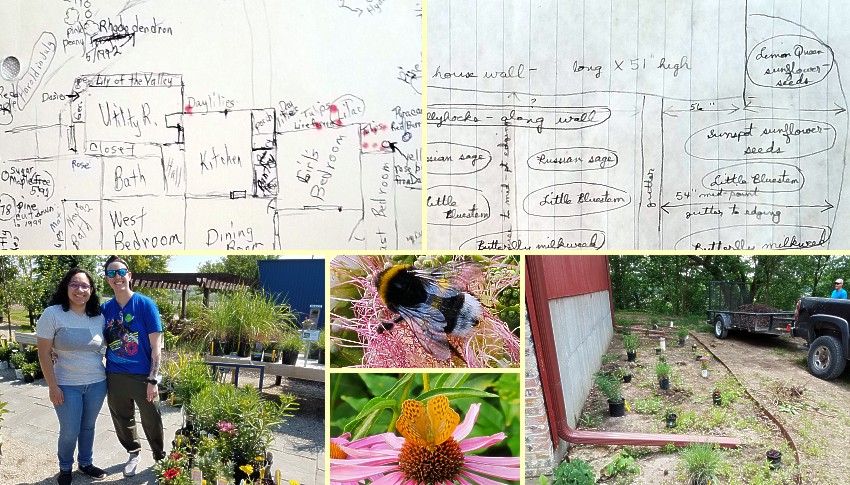

order new seeds and bulbs each year. I recently came across her drawings of flower beds, both for the farm and the folks' yard in

Manhattan. While they're not to scale and are a bit hard to follow, the details show me just how much gardening meant to her.

This year, I decided to get back in the game, but with a different approach. I would have someone else put in a small garden of

native plants that I could water every few days for the first few weeks, and then let them go since I chose drought-resistant

species. My motivation was to attract bees, birds and butterflies to our yard. I wanted to create my own "homegrown national park"

- a term coined by Douglas Tallamy, an entomology and wildlife ecology professor at the University of Delaware.

In his book - "Nature's Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard" - he proposes that each person can do

his or her part to preserve the plants and animals that are rapidly declining because of climate change and human encroachment.

Tallamy's idea is to have a large number of small projects - native-plant buffers on farms, small plantings on city lots in towns,

pots of butterfly milkweeds on apartment balconies, and pollinator "pockets" in city parks and on college campuses. The native

garden outside Kansas State University's Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art and the Prairie Garden Terrace at the Flint Hills

Discovery Center are typical examples.

Once we plant native, we can enter our efforts into the map on the Homegrown National Park website. We can then see how it supports

other pieces of habitat to create cross-country networks for threatened populations of plants and animals.

Tallamy advises we don�t have to dig up the whole lawn or cut down all invasive plants to make a difference: even a few square

feet of native plants can bring a missing species "home." The Homegrown National Park website in big, bold letters states: "We can

do this! One person at a time. Regenerate biodiversity. Plant native." Underneath, in smaller letters: "No experience necessary."

I began my own project by looking at the "Native Plants" section of the Kansas State University Research and Extension website. I

printed out several pages and took them to a local nursery to determine which species they had, and which ones were best for sunny

areas since my garden is on the west side of our house. Then I carefully made note of height, width and colors so I could design

the space to be as attractive as possible.

After, I met daughter Mariya and her wife Miriam at the nursery so they could help me select a variety of plants. They have done a

good job of landscaping with natives, and have put in brick, stone and rock pathways to reduce the amount of grass in their yard.

I expected they would have good advice for me.

In the end, we selected Little Bluestem grass, Russian sage, bee balm, butterfly milkweeds, coneflowers, lavender, and a few others.

I did some crude layouts to indicate where I wanted each plant. Randy, the "handyman" for several friends and me, planted them and

added mulch to keep the weeds out.

It's too early to tell whether my garden will actually "take," but I'm optimistic. And I've become an advocate for "homegrown

national parks," telling everyone I know about the concept.

When daughter Katie and her hubby Matt were with us in France recently, we walked through Metz' Jardin Botanique - "botanical

garden." Within the grounds, we found many native plants that are the same as those we have on our Midwest prairies - grasses,

coneflowers, and others. The garden seemed to be popular with many insects and other critters. We saw snails, butterflies, bees,

and birds throughout. Since Katie and Matt recently bought a house, they are interested in landscaping ideas. I mentioned the

"homegrown national park" concept, and they were immediately intrigued.

While I hope my small effort will do something positive for the planet, I know for certain that it will do something for me. It

will be an endless source of wonder and amusement as I watch for bees, birds and butterflies in my very own national park.