Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - June 16, 2023

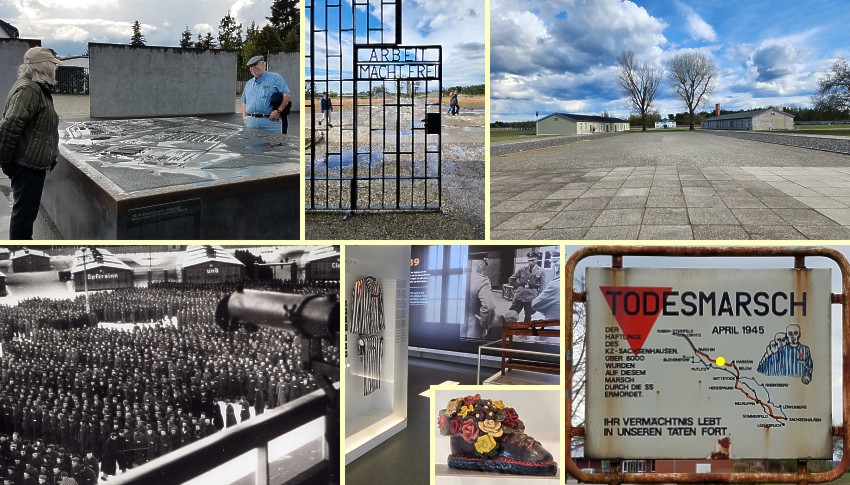

Sachsenhausen - one of many

The woman to my left on our April 11 flight from Newark to Berlin had lived in the U.S. for 20-odd years, but Germany was her

homeland. She confided she had a love-hate relationship with the country of her birth, the latter sentiment arising from the

atrocities committed by the Nazis. I mentioned our U.S. history includes examples of terrible treatment of Native Americans,

African slaves, and others.

"But the Nazi terror was committed by a sophisticated, educated society and wasn't that long ago," she replied.

Her words came back to me later. In late April, husband Art, his cousin Kris and I visited the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp

Memorial and Museum in Oranienburg, 25 miles northwest of Berlin. Art and I have visited Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau and

other KZs - Konzentrationslager - over the years. Whenever he suggests we visit another, I hesitate, yet I know it's imperative

we examine the darker parts of our human nature as well as the positive ones.

As recently as the late 1980s, Germans didn't openly discuss the Nazi years. But with reunification, that changed dramatically.

Today, those who join the German military or police are required to visit former camps as part of their training, and school

classes take field trips to the memorials.

The Brandenburg University of Applied Police Sciences has been located on the Sachsenhausen KZ grounds since 2006. Recruits are

taught "human dignity is inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority." Students learn about

the crimes committed by the state during the Nazi regime.

When Adolf Hitler became Germany's chancellor in 1933, anyone who opposed the Nazis or was deemed "undesirable" was likely to

end up in one of 110 camps. But over time, Jews became the focus. In 1939, when World War II started, Jews in the Berlin area

were sent to Sachsenhausen. As the Third Reich grew throughout Europe, the number and size of the camps increased. Sachsenhausen

eventually had 50 barracks for prisoners, a medical experimentation center, a crematorium, gallows, and gas chamber. Some 200,000

prisoners passed through the camp and about 30,000 people were murdered there. This doesn't include Soviet prisoners of war, who

were killed upon arrival and so, were not among those counted.

When the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum began documenting the camps, researchers thought there would be about 7,000. By the time

they finished, the number was more than six times larger. The 42,500 detention centers included 30,000 slave labor camps; 1,150

Jewish ghettoes, 980 concentration camps; 1,000 prisoner-of-war camps; 500 brothels of sex slaves; and thousands of others for

euthanizing the elderly and infirm.

To enter the Sachsenhausen grounds, we passed through an iron gate. The metalwork contains the words "Arbeit Macht Frei" - "work

makes you free" - as did the gates to other camps. But this camp was the first - the model for the others.

The 78th anniversary of the camp's liberation was the weekend before our visit. Dignitaries had placed flowers throughout the

grounds.

The entryway clock showed 11:07 - the precise moment on April 22, 1945 the camp was liberated. Soviet troops found 3,000 unguarded

prisoners - those too weak to join what came to be called a death march.

It and other camps were evacuated for a variety of reasons. In some cases, authorities didn't want prisoners to fall into enemy

hands to tell their stories. In others, they thought prisoners would be needed as labor in future war-production facilities. Still

others who believed their cause was hopeless speculated the prisoners might serve as hostages to forge a separate peace with the

western Allies.

In the days before liberation, about 33,000 Sachsenhausen prisoners marched under armed guard in cold, wet weather with no food or

water. Those who became unable to march were killed. When the war's outcome was clear, the guards fled. Two weeks after the march

began, surviving prisoners were found, some by U.S. soldiers and others by Soviet forces.

We watched a 20-minute film about the camp and then went to the museum. One item that caught my eye was a little shoe molded of

bread dough with colorfully-painted flowers. A 16-year-old Russian prisoner had made it from his meager bread rations not long

before he died of tuberculosis. He gave it to fellow prisoner Ludwig Peters, who later said, "This gesture came from the heart.

It was the most beautiful present of my life."

Ukrainian Mikhail Orlov wrote and illustrated a camp "song book," which fellow prisoners continued after his death in 1943.

We walked part of the grounds, which once covered 990 acres - well over a square mile. "Station Z" - a building that contained

four cremation ovens, a gas chamber and a firing squad area - was named for the last letter of the alphabet as a cynical reference

to it being the last station in a prisoner's life.

The ride back to our place in Brandenburg's beautiful Spreewald was a quiet one. Kris wondered how those who survived had the

strength to endure such a traumatic experience.

She pondered how to prevent such atrocities in the future.

... it is good that teaching kindness and compassion in our schools is becoming more prevalent ... How we get adults of the

world to learn the same is the challenge ... We need to try to lead by example and act to make our little corner of the world

more welcoming, tolerant and kinder ...

Certainly it is unwise to dwell on mistakes of the past, yet examining them can serve as a cautionary tale and help us to avoid

repeating them. Germans appear to have learned this lesson and perhaps we can learn from them - not just to build on the good

things we have done, but to avoid our past mistakes.