Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - January 27, 2023

Hard to fathom

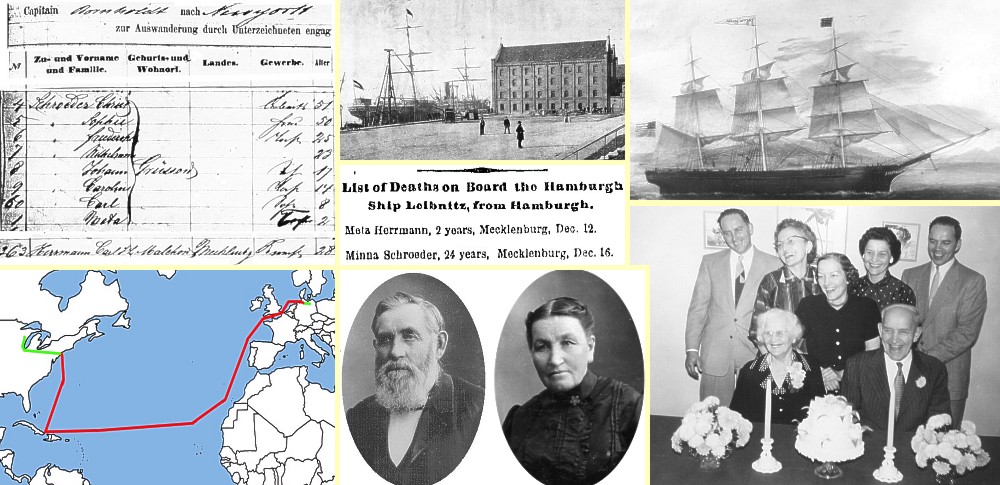

While in Wisconsin recently, husband Art and I added details to a story that unfolded 155-plus years ago - a story in which his

great-grandparents had been unwilling participants.

In 1867 Mecklenburg, virtually all land belonged to the church, the government or large estate owners. The Industrial Revolution's

arrival meant more labor was available than was needed. A holdover from feudal days, estate owners could grant or withhold

permission to marry as a way to control the labor supply. Karl Herrmann and Friedrike Schroeder received permission by agreeing to

leave the country. Her parents and siblings also left to join her brothers, who had previously settled near Greenville, Wisconsin.

The couple married on October 24, 1867.

The family sold its few belongings and immediately traveled by train to Hamburg. There they bought tickets on the sailing ship

Leibnitz, boarding on November 2. It had been built in Maine as the cargo ship Oliver Moses. Since freight doesn�t need much

ventilation or light, there were very few openings to the deck below. Planks laid across the lower beams above the bilge water

allowed the ship to accommodate more people.

Art's ancestors were just nine of Captain H. F. C. W. Bornholdt's passengers in the cramped space below deck. The ship required 25

men to handle it. The Sloman Company, the owner, hired 27 - two additional to address the needs of 544 passengers!

Headwinds required the ship to lay off Cuxhaven for nine days before weighing anchor. Reaching the top deck for fresh air or to use

one of six bathrooms was difficult and many didn't. Nature's call was frequently answered wherever a person was.

The north Atlantic is often treacherous in winter, so the ship took the southern route, hugging the European coast until off

Africa, then sailing southwest to the West Indies and then north to New York. Conditions deteriorated as the ship moved southward.

Much of the food was rotten. Passengers were given only a half-pint of water per person per day, while temperatures below deck

reached the mid-90s. Lanterns placed in the hold for light burned dimly because of low oxygen. Seeing more than a few feet was

impossible, even on a sunlit day.

On November 21, a young woman fell ill. Death came just two days later. It was thought to be cholera, but later proved to be typhus.

Soon, there were days when handfuls died. The captain later remarked how quickly the ill progressed from first symptoms to death.

The dead frequently stayed with the living for long periods before being hauled to the deck and summarily committed to the sea.

Meta, the Herrmann's 2-year-old daughter, and Wilhelmina, Friedrike�s 23-year-old sister, were two of them.

Deaths declined after Christmas as the ship sailed northward and temperatures dropped. On their January 11 New York City arrival,

35 passengers were ill. They were moved to a hospital ship and the Leibnitz was quarantined for 10 days. During the voyage, 105

died, while three succumbed after arrival - 20 percent of those who had boarded.

An inspection report gave some idea of the ship's condition.

Mr. Frederick Kassner, our able and experienced Boarding Officer, reports that he found the ship and the passengers in a most

filthy condition, and that when boarding the Leibnitz he hardly discovered a clean spot on the ladder, or on the ropes, where he

could put his hands and feet. He does not remember to have seen anything like it within the last five years.

One inspector "spoke to some little boys and girls, who, when asked where their parents were, pointed to the ocean with sobs and

tears, and cried, 'Down there!'"

The report concluded:

Under the present system, the emigrants are treated more like beasts of burden than like human beings, starved and crowded together

in ill-ventilated, ill-fitted, ill-supplied, and ill-manned vessels.

By late February, the Leibnitz was back in Hamburg. Prime Minister Otto von Bismark promised the Prussian government it would never

happen again, but the Supreme Court found the owner blameless. After being renamed the Liebig, the ship, again laden with

immigrants, sailed for Quebec. Unlike the previous voyage, the passengers were complimentary about their conditions and the captain.

German playwright Gerhard Hauptmann wrote, "The immigrant is like an apple from which everyone takes a bite." Immigrants traveled

west to Chicago on trains that frequently involved overpriced tickets and moved slowly so passengers were forced to make overnight

stops in hotels that had arrangements with the railroad to funnel business in their direction. Whether Friedrike and her family's

rail journey was one of those is unknown.

Art's relatives arrived by train in Greenville February 21, one month to the day after the quarantine was lifted. Two days later,

Friedrike gave birth to Emma, the first of her nine children born in America.

The story of the ship's misadventure had appeared in Greenville's nearby Post newspaper as well as papers from Britain to New

Zealand. While the number who died on the Leibnitz was high, it was within the range of what had been typical for sailing ships.

Fortunately, by 1870, more than 90 percent of immigrants arrived by steamship - a trip of about 16 days, about twice the time the

Leibnitz waited for favorable winds.

The public's attention had brought change. Ships were required to have a doctor on board who was not in the employ of the owner and

could independently testify to on-board conditions. Passenger health was evaluated before boarding as companies could be forced to

return passengers who arrived sickly, much as airlines today must return passengers who don't meet U.S. entrance requirements.

Two years after her infamous voyage, the Liebig was lost at sea when Captain Bornholdt ran it aground near the Pacific's Baker's

Island, apparently carrying only cargo. In 1907, now retired, he was living in Schleswig, 80 miles north of Hamburg.

Art's grandfather, born in 1879, said he didn't recall his parents ever speaking about the voyage, except to say a girl had been

buried at sea.

Today, looking at the snow-decorated winter wonderland outside our window, it all seemed a bit hard to fathom.