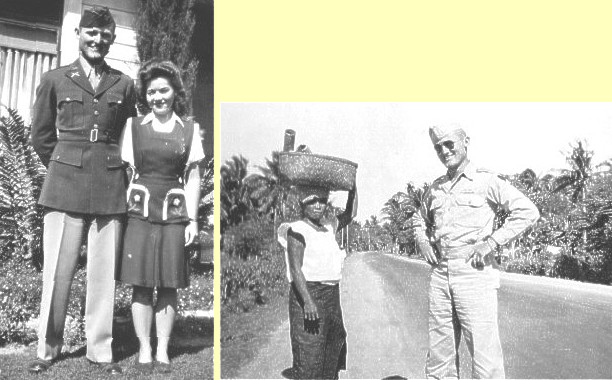

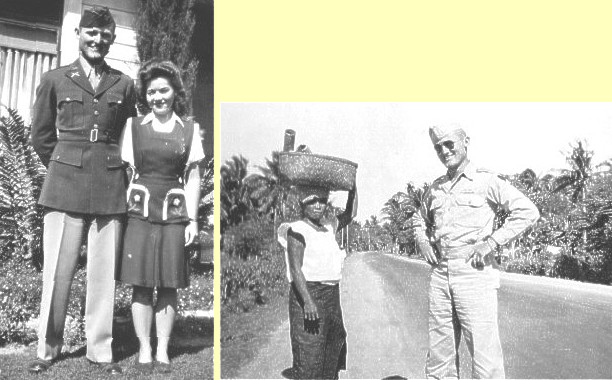

Left: Bayer with wife Margery in 1944; right: Occupation duty in the Philippines in January 1946

WWII Snapshots by Melissa M. Taylor - 2008

Burke Bayer and Margery Bayer - Army and the Home Front

Burke Bayer, born Nov. 13, 1922 and raised near Manhattan, Kan., spent his childhood on the local family dairy farm working alongside

his five siblings and parents to survive the hardships of the Great Depression.

"We had 20 head of cattle to milk two times a day and we had farmland to cultivate, wheat, corn and pasture land," he said. "The

folks were beautiful managers of their kids. Our day was completely filled on the farm, from six in the morning to six at night. We

did work a lot, but we enjoyed it and it was fun."

Bayer's father delegated responsibilities to him and his siblings on a daily basis. He said they did what they were asked because it

was what had to be done for the family to survive.

"One of my jobs was to deliver the milk, and at that time a quart of milk in a glass jar was worth a dime," Bayer said. "I would go

to the house and they would take three quarts of milk. I would take three glass jars full of milk and put them on the porch and pick

up the empties and there would be 30 cents in one of the empties to pay for the new milk. One day on the farm, Dad and I were walking

from one place to the other talking about money and debt and so forth and he said, 'Burke, that money you have in your pocket is the

only money this family has, take care of it.' I remember that so well, it sent shivers up and down my spine. Boy, did it make an

impact on me from having that money."

The impression Bayer had as a child holding the family's income in his pocket remained with him throughout childhood and into his

early adult years and later influenced his military career.

At 20, Bayer enrolled at Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science as an agronomy major and lived in Van Zile Hall

while on campus. Although he remained involved in the family dairy farm, delivering milk before classes, Bayer soon became occupied

with the college's Reserve Officers' Training Corps.

"An agriculture major was required to take a course in the ROTC program," he said. "That was my first experience with the military

and it wasn't a choice, it was a requirement. In a way, it helped me finish school. The war broke out when I was a freshman and the

ROTC program gave us the opportunity to stay in school and graduate if we went to summer school and if we joined the Army."

During his sophomore year, Bayer married Margery Campbell and he said it was a turning point in his life. The news of Pearl Harbor

came as a shock to Bayer who was on campus eating his lunch when the reports broke out.

"I remember like it was yesterday," Bayer said. "I guess I never thought too much about what the war meant for me individually, but

it certainly put a different emphasis on school and in my education. It didn't change my course of study however."

While engineers were directed toward the Army Air Corps and the Navy, agriculture majors were assigned to the Army. Bayer shipped out

for Officer Candidate School after graduating in 1944. He was sent to Fort Benning, Ga. for six months to train for the war in the

Pacific.

"I had enrolled in school (OCS), been in school about a week and the physicals we had taken showed I was color blind," Bayer said.

"So they pulled me out of classes and put me in a casual company [unit for trainees in transition] trying to decide what to do with

me. A week or two later they came back and said, 'We can use you after all, get back in school.' I think that had a bearing on how

I was assigned."

The original class Bayer would have graduated with was sent directly to Europe as front linemen, but because of his removal from

training, Bayer was reassigned and did not go directly to Europe. His time in casual company, a transition unit the Army created

for soldiers who were removed from classes for various reasons, was one of the lucky moments in his military career, Bayer said.

He was appointed ammunitions and pioneer platoon leader and had different responsibilities than 90 percent of the graduates that

went into the school.

While the majority of graduates were assigned as infantry platoon leaders and led rifle platoons, Bayer was responsible for hauling

ammunition for the battalion as well as transporting tools for dynamite blasting, chainsaws for cutting trees down, and tools

necessary for light engineering work.

In September 1944, Bayer left OCS and was sent to Camp Livingston, in Grant Parish, La., to join the 86th infantry. Within the

infantry, he was placed in the 342nd regiment, second battalion and in the headquarters company. Within three weeks he was ordered

to Camp San Luis Obispo, Calif. to go through three rounds of training for the Pacific. He primarily did amphibious training in

preparation for being an island-hopping division in the Pacific and for the invasion of Japan.

"We got off the big ship, got down the rope ladders and then got on the landing boat with 15 to 20 guys," Bayer said. "You're

maneuvered in the water to get to a flat boat and then you go up with every wave, up, down, up, down and that's what did me in. We

were getting ready to head to the beach, 10 or more Higgins Boats in rendezvous out in the ocean, circling getting ready for landing."

When the men got to the beach, the ramp at the front of the boat dropped down. The men then left the boat and went into battle from

there.

"I had already lost my beans before that point," Bayer said. "I couldn't even walk. I just told the guys to 'Just go ahead, I'll

catch you and then crawled out of the boat and just lay on the beach."

After Bayer spent seven months training for the Pacific in California, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower decided he needed two more divisions

in Europe after the Germans made a breakthrough in the Ruhr Pocket, a territory Germans had seized for their control. Eisenhower

requested that Bayer's unit, the 86th, as well as the 42nd, be sent to Europe. Until that point, Bayer, who was a second lieutenant,

had not really thought much about what the war might mean to him personally. The thought of leaving his wife behind made the conflict

in Europe seem real.

"My wife was with me in California and that was the first time that I really said to myself, 'This might be it, I may never see her

again,' so that was the only time that I was really uptight about what might happen," he said. "It was exciting in a way because of

new territory. I had never been overseas."

For Margery Bayer, being separated from her husband was difficult.

"It was hard, but being young, you sort of handle those things better," she said.

After departing from California, Bayer was shipped to New York City, N.Y. where he boarded a Swedish luxury liner and began his first

ocean voyage to Europe. As an officer, he was given upper deck privileges and was able to eat in elaborate dining halls with ornate

chandeliers.

But the luxury did not last long and as the ship docked in Le Havre, France, Bayer observed firsthand the results of the war.

"Le Havre had been bombed extensively and seeing the first results of combat, well you knew where you were and you got another

recognition of 'Here we go,'" Bayer said. "I didn't know where we were going to go and I didn't know of the geography of the combat

at the time. We ended up at a campsite in the Le Havre area, named after cigarettes, Lucky Strike, Old Gold and Chesterfield."

Bayer was assigned to Old Gold, a camp he described as a tent city and a transition zone. The first few days in camp were used

primarily to get settled and get a feel for what was going on within the country. A few days after landing in Le Havre, Bayer and

his infantry set out to find anti-tank mines to practice uncovering them.

"The first time I saw an anti-tank mine was on a coastline buried with them," he said. "We thought we oughta go and see if we could

remove some of them to get some experience. We went out and found one. You dig around with your knife to be sure of where it is and

you tie a rope onto it, to pull it out of the hole. But you don't pull it out right away because sometimes they put an anti-tank

personnel mine underneath the anti-tank mine. If you move, it goes off. So we got back in the next hole over, pulled on the rope and

it got caught up on some barbed wire as we pulled it out of the hole. Someone had to go out and unhook it. They asked for volunteers

and nobody would volunteer. So I went out and that was the first time I thought, 'Wow this isn't good,' but I unhooked it, and got

out of there."

Before shipping out to OCS training, Bayer had worked with his father at the family construction company, doing quarry work. His

background in working with explosives helped him overseas to disarm anti-tank mines.

Bayer and his platoon remained at Old Gold for several weeks before being assigned to the front lines. The Army trucked the infantry

to the nearest railhead and everyone loaded up on a Forty and Eight, a rail car that could haul 40 people or eight horses.

"The rail cars were relatively small and didn't have windows; there was a sliding door on each side with bales of straw on the floor

and no facilities," Bayer said. "Each man carried with them their barracks bag, a 60-pound bag with all belongings. We got on the

train, they shut the door and it was dark. We stopped every five to six hours to get out and stretch."

The rail car trip lasted two days and two nights and went through France, Luxemburg and into Germany. Bayer and his battalion ended

up 30 miles from the front lines where they unloaded, and took trucks into Cologne, Germany, on the Rhine River.

"At that point, the Germans were on the other side of the river from where we were," Bayer said. "Our first organized job was to

defend the river, so we stretched out up and down the Rhine River in a defensive position. We were getting artillery shells from the

Germans from the other side of the river. It wasn't bad. There was no rifle fire, just artillery and it was sporadic. We didn't take

any precautions. We just went about what we had to do."

With the war unfolding around him, Bayer did not have time to think about home and what he was missing.

"I don't know if I had felt it yet," he said. "I had 15 to 20 guys in my platoon and I was responsible for those guys. So 24 hours a

day that was my responsibility. I was like a mother hen with 20 guys, 24 hours a day and I really didn't have time to think about

myself. The reality of it was, I didn't think much about home. Every day was all encompassing for me and I didn't have time to mourn

what I was missing."

While Bayer was consumed with responsibilities overseas, Margery Bayer was working and taking several classes at Kansas State

College, now Kansas State University. Even though she did not participate in the war, she said the majority of people on the home

front were involved in some activity to support it.

"Everybody was more or less involved and supporting it," she said. "They did bond drives, or bought war bonds. People were also

encouraged to raise victory gardens because food was rationed, more so in later years, but everyone was pretty much behind the war

effort."

Meanwhile, back in Europe, Bayer's unit had just crossed the Rhine River with 20 other divisions. They were assigned to reorganize

the Ruhr Pocket, an area 190 miles long and 90 miles wide, which was filled with German troops and had been encircled by American

troops.

"Our job was to drive right through the middle of the pocket so the Germans couldn't work cross lines," Bayer said. "We had trucks

for the troops and all the equipment so we could drive straight through and we didn't stop unless the Germans stopped us with

firepower. Even if they were firing from the hills, we kept going, which was plumb scary because we knew they were behind us."

Bayer said the Germans had a large number of slave labor camps and they began picking up prisoners from those camps. The majority

of prisoners were kids - straggly, dirty and hungry, Bayer said. There were also Schutzstaffels also known as S.S. Troops, who were

part of an elite Nazi military organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. A group of them came out of the hills in full

uniform and surrendered directly to Bayer.

"We stopped at this one little town and down the road there were these S.S. Troopers," he said. "They walked up to me and one of

them handed his Luger (German pistol) over to me and surrendered. They looked sharp and well fed in contrast to the soldiers coming

out of the hills who were haggard, dirty and straggly. That was our first real experience with them (the Germans)."

Bayer's infantry had long days and nights and, with the unit constantly moving, there were times when they would continuously drive

between towns. When the kitchen truck remained with the unit, he ate well, but he constantly carried cookies and crackers in his

pocket for times when the infantry was ahead of the kitchen unit.

After the Ruhr Pocket, Bayer's platoon headed toward the Alpine Mountains in a non-stop 12-day journey, covering 250 air miles and

crossing seven rivers.

"Everybody was exhausted and it was dangerous because people ran into one another," Bayer said, "but Eisenhower was concerned that

Hitler might have another trick up his sleeve. The first time it was clear, some of us went into Austria and met some girls, probably

high school age, and one of our guys could speak German. We asked the girls, 'What do you think of your Mr. Hitler now?' and they

just replied, 'He�s still alive. He'll be back, be patient.' It was a beautiful example of how inoculated the youth were."

A few days later a messenger came by Bayer's unit and announced the war was over. Bayer said it seemed unreal.

"A few days after that they came back and said we are going to the Pacific," he said. "My truck driver told me, 'Lieutenant, my legs

have gone numb. I can't walk.' I said, 'Come on, what's wrong with you?' He said, 'Honest, I can't.' So I called the battalion medic

to look at him. He had a momentarily lapse because he heard we were going to the Pacific and he really had a reaction to the

possibility of going there."

Two days later, Bayer was shipped home for a 30-day leave and then reported to Camp Gruber, Okla. to retrain for the Pacific. Bayer's

division was the first to serve in both theaters.

"Soon after we got there (Camp Gruber), the first atomic bomb was dropped," Bayer said. "We felt like that was the end of the war,

but one or two days after the bomb, we got orders to ship out to the Pacific. We stopped everything and in two days we were on trains

going to California and in another two days we were on ships going to the Pacific. We had been out of San Francisco for five days and

they dropped the second bomb and the ships kept on going; we never turned around."

Bayer then served a year's occupation duty in the Philippines after the Japanese surrendered.

"We were slated for the Pacific in our first training and the European war kept us out of the Pacific," he said. "They didn't know

even after the second bomb if the Japanese were going to surrender. Later we saw plans for invading Japan and our division was one

of the leading divisions. We dodged the bullet with our trip to Europe and we also dodged a bullet with the second bomb."

After serving two years in training and two-plus years in active Army, 42 days of which were spent in combat in Europe, Bayer was

discharged at Camp Beale, Calif. in August 1946 as a first lieutenant.

"The first thing I wanted was a glass of milk and they knew that and were ready for me," he said. "The big glass bottle hadn't come

out yet before the war. In California they had a two-quart jar sitting on the table and I said, 'Wow, have I been gone that long?'"

While Bayer was catching up on what he had missed, his wife was just glad to have him safely home.

"Everybody I knew had their guys in the Army or service of some kind and we all kind of accepted it," she said. "I'm really proud of

what he did and real interested in what he experienced. (When the war ended), it was great. It was like winning a basketball game.

We built up to it a little bit, so everybody was expecting it, but when it did happen it was such a big relief."

With the Army behind him, Bayer settled down with his wife in Manhattan and began a family while working in the family construction

business. But his experiences in the Army during World War II were never far from his mind.

"I enjoyed what I was doing," Bayer said. "I felt challenged by it and I was looking for a challenge. It was a wonderful experience

for me, in leadership primarily. I got to see the world and I enjoyed it. I think it took a lot of the wanderlust out of my mind."

Bayer's life was greatly influenced by the war, but he never boasted of his accomplishments or spoke much of his experiences when his

children were young.

Becky Tadtman, Bayer's daughter and youngest of three, said her father had recently renewed his interest in connecting with other

veterans and commemorating the sacrifices that generation made. Bayer joined the 86th Blackhawk Division Association, Inc. more

than 15 years ago and remains active in coordinating memorials and sharing his experiences with other World War II veterans.

"He never spoke about it (the war) when I was growing up," she said. "So I never felt it directly influencing me. But the war helped

to mold him into the person he is today; his values, his perspectives and sense of country came through him, to us. I think the war

affected him in ways unseen. He is a man of few words and I think it built his character and determination and made him who he is.

He is very patriotic, proud of the country and what he stands for and a lot of that comes from serving in World War II. (His

involvement) makes me incredibly proud. The sacrifices that entire generation made were phenomenal and they have so much to teach us,

so much to offer."

Left: Bayer with wife Margery in 1944; right: Occupation duty in the Philippines in January 1946