WWII Snapshots by Christopher Renner - 2008

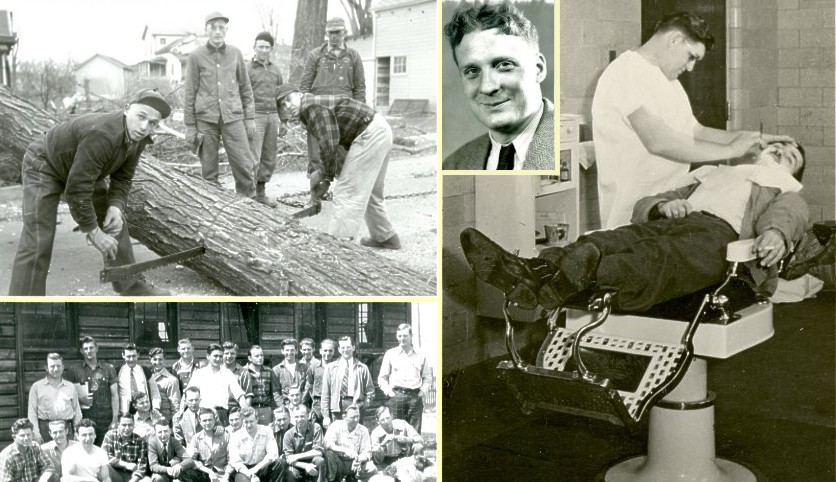

Charles Perkins, Conscientious Objector

The victors write the history. But often pieces of the story are left out or lost to time, especially pieces that don't quite fit with

the legends that arise around a historical event.

World War II was fought between the Axis Powers – principally Germany, Italy and Japan - against the Allies - the U. S., Great Britain

and her colonies along with Free France and other nations as they were liberated. It is often referred to as the "Good War."

Today the number of those who served in World War II is dwindling, but efforts are underway to capture the stories of those who

served so the whole story of World War II can be preserved, including those that don't quite fit. Charles Callahan Perkins lived one

of these latter stories.

Perkins earned his Ph.D. in 1946 at the University of Iowa. His career would lead him to Kent State University, Emory University -

where he was department head from 1961-1964, and finally Kansas State University, from which he retired in 1986 after 16 years. But

despite these accomplishments, perhaps it is the story of his involvement in World War II that is the most remarkable. And it isn't

a story like those you will find in the World War II kiosk at the Robert Dole Center in Lawrence or in the many story projects that

have begun to record the tales of heroism and bravery that the men and women who fought the "Good War" have to tell.

During World War II, 34.5 million men registered for the draft. 72,354 applied for conscientious objector (CO) status. Approximately

25,000 of those COs served in non-combatant roles while some 29,000 were exempted when they failed to pass the physical exam. Exact

numbers are difficult to confirm because the records of those classified 4-F (physical defects) are not complete. Over 6,000 men

rejected the draft outright and chose to go to jail instead of going to war. Also, 12,000 men chose to perform alternative service

in the Civilian Public Service (CPS). Perkins was among these men.

Preparing for War

Although rarely mentioned in the history books, America has always had COs. George Washington specifically exempted those "of tender

conscience" from induction into the Continental Army. The nation's principle of religious freedom brought Mennonite, Amish,

Brethren/Dunker and many Jews seeking to escape compulsory military service in Europe.

America's numerous utopian experimental communities often included a commitment to peace and nonviolence. But until World War II, a

pacifist or conscientious objector in America usually had few options: violate one's conscience by serving in the military; pay for

another to go in their place (an option until the Civil War); flee to avoid service (draft dodging); or prison.

The imprisoning of thousands of men who were COs in World War I divided the country. Scott Bennett's Radical Pacifism: The War

Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963 provides a complete historical overview that led to the decisions

by the Roosevelt administration and Congress to handle COs in a different way.

In the months leading up to World War II, Congress recognized "CO Status" as a legitimate moral position for the first time in U.S.

history. Under the law, objectors had two choices — they could go into the military but serve in non-combatant roles such as the

medical corps, food preparation, staff clerks, etc., or they could do "alternative service" at home that was "work of national

importance" in the Civilian Public Service (CPS).

The CPS was a response to the first peacetime draft in U.S. history, initiated more than a year before Pearl Harbor. It was the

product of a unique and conflicted collaboration between the U.S. government's Selective Service and the traditional peace churches:

Mennonite/Amish, Church of the Brethren and Quakers. It was also the first time COs were offered legal alternative service under

civilian command.

The churches' goal was to prevent the fate COs suffered in World War I — including verbal harassment, physical beatings and death —

and allow them to do "work of national importance" as an alternative to military service. The churches funded the CPS program with

$7 million in donations.

The motivation for the government came in part from the fall-out caused by the lack of CO status in World War I and in part from a

fear that COs would have a negative impact on wartime morale. The government wanted to keep COs out of sight and saw the CPS as a

means to that end.

But despite the lead taken by the peace churches, CPS men were not limited to members of those churches, for more than 200 religious

groups and others, like Perkins, without church affiliation, were involved. Their only shared philosophy was the rejection of war.

"I just didn't believe war works and believed refusal to participate was a way to stop wars eventually," Perkins said. "I had read

Gandhi and Millis' Road to War which had an effect on my thinking, but the Grand Inquisitor in Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov

probably had the greatest impact in that it showed me that people could do the worst things based on the best motives."

Becoming a CO

The process for being classified as a CO was pretty straightforward. The candidate appeared before his Draft Board to make his case.

Those members of the historic peace churches were granted their status based on their religious affiliation. Perkins never met with

his draft board in Cambridge, Mass.

"I guess I had to write something stating my position, but I don't remember. I spent about a year thinking about war and war

resistance and it was tough going. It is hard to take a position on a vital issue with which none of your friends or relatives

agreed," he said.

In any case, his status as a CO was approved and he received his orders to report to a Mennonite-run camp in Henry, Ill.

Perkins and his wife Nancy Phillips were married in July 1942, two months before he was to enter the camp. They were hoping he could stay

closer to Nancy, who was still working on her graduate degree at the University of Iowa, but other than for a few months when

he was assigned to a state hospital in Michigan, Nancy wasn't with him.

"COs varied in a lot of ways," he said. "Some were political objectors. A large number of them just plain refused to serve."

Some were sentenced to prison as a result. In fact, one out of every six men in U.S. prisons during World War II was a draft

resister.

"I might have joined those who just plain refused, if I hadn't received the medical discharge," he said.

"As far as I could tell, just about everyone I knew supported my decision to be a CO, but few, if any, agreed with my position,"

Perkins said.

The life of a conscientious objector was often extremely difficult, especially for those who were not members of the traditional

peace churches. COs who were Catholics, Jehovah's Witnesses, Muslims or Jews often found that their friends and family as well as

society as a whole rejected them.

"I think this depended on the CO," Perkins said. "If he was sincere and open about his beliefs, he was accepted or at least not

hassled openly."

But it also depended "on the sort of people he had contact with," he said.

People in the CPS had about the same amount of leave as someone in the military service and Perkins sometimes used that leave time to

engage in discussions with others about being a CO.

"Riding on trains during leave, I would bring up the fact that I was a CO, if it could be worked into the conversation, and had some

good discussions, but no converts," Perkins said.

During World War I, Mennonite, Brethren and Quaker COs often faced violence for their pacifist beliefs. Melvin Gingerich in his book

Service for Peace, a History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service, reports that more than 2,000 COs were imprisoned in World War I

because they refused to take up arms.

Will McKale, archivist at Fort Riley's Cavalry Museum, confirmed that two Mennonites were beaten at Fort Riley for their refusal to

take up arms during World War I. So there were good reasons for the fears experienced by COs during World War II.

"The Mennonite guys tried to avoid conversation with strangers for fear of violence," Perkins said.

It was hoped that the CPS system would eliminate these problems. Yet CPS camps members found themselves reviled by the communities

located nearby. In PBS's The Good War, World War II CO Martin Ponch gave an example of the resentment CPS members encountered when

he told how the City of Plymouth, N.H. allowed nearly a third of the city to burn down rather than call on the services of the

trained firefighters at the CPS camp outside of town.

Life in the Camp

COs began receiving orders to report to CPS camps early in 1941. Most expected to stay for six months based on government-issued

information. But most COs would stay in the camps for the duration of the war. Others were not released from duty until 1947, two

years after World War II had ended.

According to Albert Keim in his book The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service, COs were required to work

nine-hour days, six days a week, often at hard labor. In addition, they were expected to pay the government $35 a month for their

room and board. Those that could, covered this expense on their own. But for many, their congregations covered this expense at

great cost. The congregations also provided $2.50 a month for expenses. But the families of married COs had no such support. For

many of them, the war years were a time of dire poverty.

Perkins was in the CPS for one and a half years before receiving a medical discharge. Following his first assignment at Henry, Ill.,

he was transferred to Downey, Idaho, where he worked in soil conservation.

"Soil conservation was done mostly by the shovelful," Perkins said. "The regular soil conservation men who assigned the work were

not permitted to have COs do work that would put them in regular contact with farmers that the service had contracts [with]."

As a result, the CPS members mostly worked on isolated projects.

Finally, he was assigned to a state hospital in Michigan where he performed the duties of a registered nurse, even though he had no

formal training as one.

Life in the camp "was a case of culture shock. I had refused to claim religious grounds [for my status as a CO] and almost all the

other campees there were fundamentalists," Perkins said. "Their attitudes were very different from mine. In Henry, there was a fair

amount of conflict between a small group of radicals and the Mennonites in control. The radicals wanted things to be done

democratically."

Camp life was pretty routine.

"You got up fairly early, had breakfast and then were driven to where ever we would work," he said. The men had a fair amount of

free time, which was spent talking to other COs, or in Perkins' case, writing letters home to Nancy.

"The camp in Idaho was a little more liberal. About half were people who thought in terms of the social effect of war and weren't

really religious," he said. Such thinking was more in line with Perkins' own beliefs.

Long-term contributions

Beginning in 1942 and following agitation and work walkouts, COs began to take on responsibilities not originally foreseen by those

who organized the CPS. COs began to fill the rank of those working in mental institutions that had seen their employees leave for

better-paying jobs in the war industries. According to The Good War, more than 3,000 COs worked in 41 mental institutions in 20

states, and at 17 training schools for "mental deficients" in 12 states. This work is perhaps the most significant long-term

contribution World War II COs made to the national welfare.

Perkins' work in Michigan was an eye-opening experience.

"The state hospital was pretty bad, but not as bad as some of them," he said.

In The Turning Point, Alex Sareyan discussed how the conditions of these institutions were extreme with patients often suffering

cruel and inhumane treatment at the hands of institutional officials. In response, COs introduced nonviolent methods of patient care.

In some cases, they took legal action. A lawsuit won against the state of Virginia for inhumane treatment of patients contributed

to the founding of what became the National Mental Health Foundation.

Sareyan points out that the COs' most important work led to a 1946 Life Magazine exposé that brought national attention to the issue

of mental health and the treatment of patients. Life reporter Albert Q. Maisel's story was based on first-hand accounts by COs. Their

reports shocked the nation as they revealed the squalid and repressive conditions in mental institutions and led to reforms that

influence the care of mental patients to the present day.

But Perkins doesn't feel that he had much effect on others or that the reactions of others toward him as a CO had much effect on him.

"I don't think my time as a CO had any effect on me in terms of people's reactions," he said. "I came to my views very much on my own.

Most of my friends volunteered for the military. My brother was a paratrooper who fought in the Philippines, one sister was a WAC and

the other lost a husband who was serving in the Navy."

"What it did was make me more committed to social issues," Perkins said.

That commitment took the form of Perkins getting involved in the civil rights movement during his time in Atlanta and in Iowa City.

"The people in my age group that I run into talk about nonviolence, but back then no one used the term," Perkins said.

Nonviolence is how many of his generation today reach out to new COs, including those who come to their thinking based on their

experiences in the military and what they have been asked to do.

But there aren't too many people in Perkins' age group any more and, at 91, Charlie Perkins is moving a little slower than he did in

1941. Two years ago, he and Nancy, his wife of 62 years, moved to Seattle to be closer to their grandchildren and Perkins' favorite

fishing spots in Montana. But he still recalls those days of 66 years ago clearly.

Timeline

1940

July 1 - Congress passes the Selective Service Training and Service Act of 1940 creating the first peacetime draft in US history.

Signed by President Roosevelt on Sept. 16, conscientious objectors (COs) are exempted on the basis of training and belief.

Oct. 5 - Historic peace churches — Quakers, Church of the Brethren and Mennonites — form the National Service Board for Religious

Conscientious Objectors.

Oct. 30 - Conscription begins.

Dec. 17 - Civilian Public Service (CPS) is established. COs serve their country by doing "work of national importance." The federal

government and the peace churches jointly create 151 camps across the country to inter legal COs.

1941

May 15 - First COs ordered to report to CPS camp at Patapsco, Md.

Dec. 7 – The Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor. The United States enters the war.

1942

Feb. 16 - COs walk out at Merom, Ind. CPS camp because of the lack of "work of national importance."

March 5 - COs begin performing other tasks (smoke jumping, mental hospital attendants, human guinea pigs) at detached CPS units

outside of camps.

June - First CPS unit arrives at Eastern State Mental Hospital in Williamsburg, Va.

1943

June - First CO smoke jumpers in Missoula, Mont.

Dec. 23 - Segregation at Danbury Federal Prison ends in response to a four-month work strike by 23 COs.

1944

January/February - The CPS Union organized at Big Flats, N.Y. CPS camp. Provides an organized means of communication and group

action among COs nation-wide.

June 24 - COs volunteer as guinea pigs for influenza and pneumonia experiments.

1945

May 7 - Unconditional surrender of all German forces to Allies.

Aug. 6 - First atomic bomb dropped, on Hiroshima, Japan.

Aug. 9 - Second atomic bomb dropped, on Nagasaki, Japan.

Aug. 14 - Japanese agree to unconditional surrender.

Oct. 24 - United Nations is officially born.

1946

May - COs who worked in mental hospitals establish the National Mental Health Foundation.

Life magazine reporter, Albert Q. Maisel, writes an exposé based on first-hand accounts by COs that shocks the nation as it

reveals the conditions in mental institutions.

1947

April - COs George Houser and Bayard Rustin and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organize the first Freedom Ride through the

South.

Last COs released from CPS camps.