Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - September 4, 2020

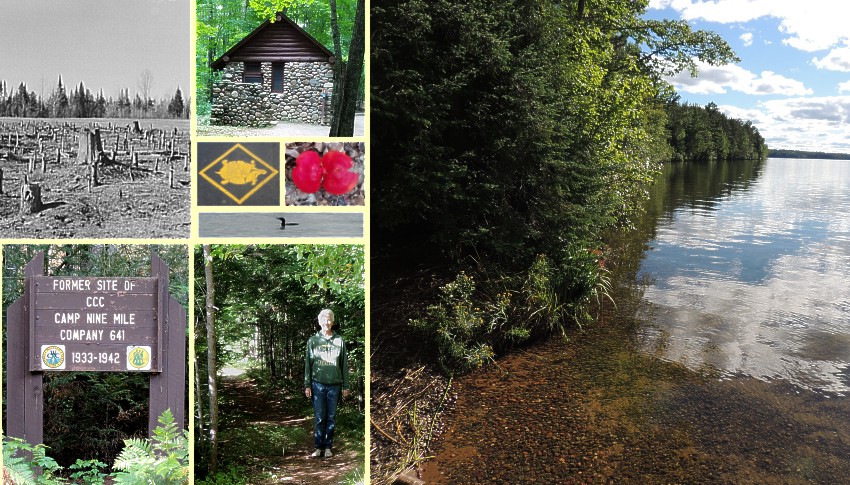

From clear-cut to conservation

In 1993, I gave husband Art an anniversary "gift" of two weeks at a cottage in Northern Wisconsin, prompted by his comments about

how much he enjoyed his years of trout fishing in his native state. We, our then-young daughters Mariya and Katie and Art's mother

Donna enjoyed our time so much that we bought a place there the following year.

While the cool summer temperatures, lake views, cranberry bogs and small villages are a welcome change from the hot summer plains

of my native Kansas, I particularly enjoy the pines, birches, tamaracks, maples, hemlocks and other trees that provide a canopy

over the winding rustic roads of the nearby Chequamegon (she-quam-uh-gon)-Nicolet National Forest. Raspberry, blackberry and

occasional blueberry bushes, brown-eyed Susans, purple thistles, goldenrods and mushrooms "blossom" below the towering trees. Here

and there, a glints of sunlight are seen from almost-hidden lakes. Deer, wild turkeys, geese, squirrels, chipmunks, loons, black

bears, and other wildlife are abundant.

But with this natural beauty, it is hard to imagine that less than a century ago, much of the region was barren - clear-cut to

provide lumber for railroad ties, ships, homes, barns, churches and the businesses of our fast-growing country. Following the

pattern set in the southern part of the state, once the trees were cut, the land was sold to immigrant farmers, then mainly from

Finland, Poland and other Eastern-European countries. But the mixed sandy and boggy soil was not conducive to farming. The

economic hardships of the late 1920s and 1930s saw these newcomers forfeiting their lands, unable to pay the taxes.

In the late '20s, Donna's friend Frieda told her of a cabin next to a beautiful tree-lined lake north of her home in Appleton. All

winter, Donna and pals Grace and Myrtle planned their vacation for the following summer. But when they arrived, they discovered

the loggers had been through during the winter. "There wasn't a stick of a tree anywhere to be seen," Donna said.

That story had a happy ending. The women left, locating a place farther south, where a grocery-shopping trip led to Donna meeting

Art's dad.

The hard times of the Great Depression also provided an opportunity that led to a similar outcome for those then-barren lands.

Desperate for money, counties sold the seemingly worthless properties to the federal government. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's

New Deal included the Works Progress Administration (WPA), National Youth Administration (NYA) and Civilian Conservation Corps

(CCC) - programs which offered employment to jobless Americans.

Of the CCC, the president told Congress:

I propose to create [a program] to be used in complex work, not interfering with normal employment and confining itself to

forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects.

From 1933-1942, the CCC provided work for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18-25, later expanded to include those between 17-28.

Three million were given shelter, clothing, medical care, food and job training. Paid $30 per month, $25 had to be sent home to

their families. Familiar names among its alumni include actors Raymond Burr, Robert Mitchum and Walter Matthau, test pilot Chuck

Yeager and professional baseball player Stan Musial. Environmentalist Aldo Leopold was a technical forester. In Wisconsin, the

CCC employed more than 75,000.

Thanks to the program, biologists say the bio-diversity present in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest today is the same as it

was before the first white settlers arrived. The million and a half acres is today managed by coordinated efforts of federal

agencies, tribal leaders, city, county and state governments, conservation organizations, universities, non-profit organizations,

neighboring landowners and private citizens. They control fires, restore watersheds, monitor wildlife, improve fishery habitats,

inventory and monitor archaeological and historic sites, and conduct conservation-education programs.

But the lands are not just to provide a home for feathered, finned and furry creatures. People can hunt, fish, birdwatch or just

enjoy a meal over a campfire in a setting that makes them feel disconnected from the demands of an otherwise busy life.

On a recent Sunday, Art and I drove to the Franklin Lake Campground about 20 miles from our cottage. It was a 1936 joint venture

of the CCC, the WPA and the U.S. Forest Service. World-War-I-veteran enrollees constructed the buildings with fieldstone and

saddle-notched logs, creating a "rustic" look. The buildings today are unchanged, except for the effect of routine maintenance

and the addition of modern plumbing. In 1988, the Campground Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic

Places and the State Register of Historic Places.

Each camp sites include a picnic table, a fire pit, and access to wells with drinking water, a boat landing, a swimming beach,

flush toilets, and a seemingly unlimited number of walking trails. The campground is one of more than 100 nearby sites associated

with the CCC work in the national forest. There are buildings, bridges, pine plantations, former camps and fire towers. Some are

in use, others have been reconstructed, and some just have pieces remaining. Others have vanished completely.

In spite of seeing many tents and RVs along the access road, each campsite seemed remarkably quiet, the silence broken only

occasionally by the chatter of a chipmunk, the breeze through the trees or the distant voice of a child. The lake

water was crystal clear and undisturbed, save for a single boat and a loon diving for fish. Art, who has spent many hours in the

woods fishing and avoiding people, was impressed. A check of the reservation website revealed almost all five-star ratings for

the campground�s $18 and $15 sites.

We often hear about the failures of government programs, but successes rarely make headlines. Those who worked to restore it back

in the 1930s and 1940s, along with the managers of today, can be proud of their efforts.