Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - July 3, 2020

From Aikman to Zitnik

This year is the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. Husband Art and I have no direct memories of the war, but our talking

with my uncles Bob, Bud and Stan and Artís uncles Art, Pete and Rollie, all of whom served during the war, piqued our interest. Hearing

our parents and other family members speak about what life was like on the home front encouraged that interest.

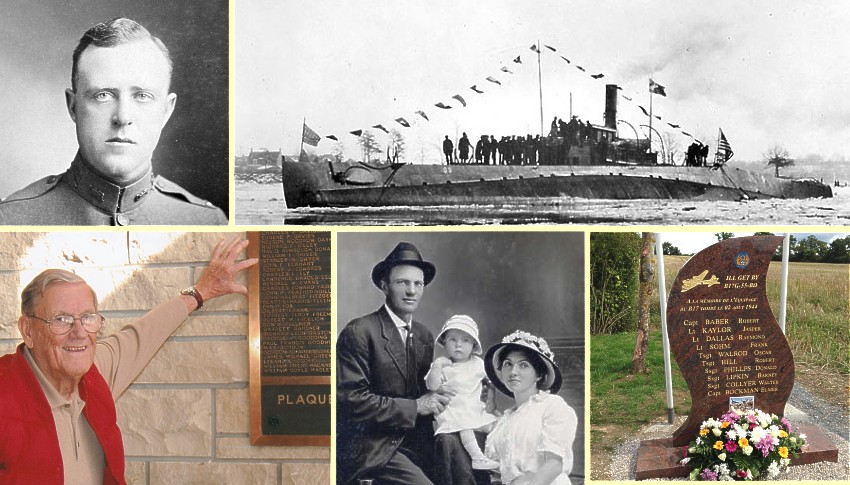

We began a related "small" project five years ago - biographies of the men from our own county who died in the war. Art has done the

tedious work of gathering information, while I've written columns and news articles about some of them.

It began with Vernon Bates, a World War I veteran and one-time commander of the local American Legion post. He completed his list of 101

names in the late 1940s. Art added those of the Kansas State College (now Kansas State University) men named on a plaque in its

All Faiths Chapel. He included the names of others, such as men who had declared Riley County as their home. The current total is 347.

Art's process ranges from quite simple to very convoluted. He starts with a general Ancestry.com search and then adds sites such as

those for newspapers.com, the American Battle Monuments Commission, Find-a-Grave, Google and others. During the searching, he found a

1943 article about Bates' effort to compile his list.

Art is extremely persistent when tracking down some obscure piece of information that might yield a clue as to whether a man had a wife.

Other times, the information comes so easily it may take less than a few hours. He sometimes works day after day on the list, while

at other times, he'll let it go for weeks when he is busy with other projects.

To stay organized, he created a computer folder for each man and a computer spreadsheet with one row per vet. There are columns for the

name, service serial number, rank, branch of service, what list(s) he appears on, cause of death, dates of birth and death, enlistment

date, parents' names, wife's name, if married, children's names, if applicable, whether a photo has been found and, if it exists,

the burial plot location. Most of those spreadsheet items are now filled in.

While most died as a direct result of battle, about 25 percent died from accidents or disease. One was even found to be alive! He had

been adopted and his name was changed to that of his adoptive parents. His biological dad had used the boy's birth name to inquire and

was mistakenly told his son had died in Italy. That led to the boy's birth name going on the Bates list. In reality, the young man

returned home after the war and was working in the Veterans' hospital just 60 miles from where his father lived. A common friend, who

was aware of the name change, saw the name on the Bates list which led to bringing father and son together.

A few men died before the conflict began while our armed forces were preparing. A couple died after the war - Karl Niemann succumbed

in a barracks fire in Japan, apparently arson by a disgruntled Japanese man. One man's war lasted only minutes. He was killed on the

USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack that triggered the United States' entry into the war. Two died delivering

aid to partisans during risky secret nighttime flights. At least one died when the Japanese were moving prisoners. Not knowing they

were on board, our boys bombed the ship.

Early in the war, fuel and bombs were flown over the Himalayas to China. When enough was stockpiled, bombing runs were made on Japan.

But the mountain weather was very changeable and men were lost during these ferrying flights. Fighter planes - called pursuit planes

then - were generally one-man ships designed to be used over land. When the B-29 bombers began to hit Japan, fighters were sent along

over the ocean to protect them. But encountering clouds could be a death sentence for a fighter pilot. Emerging from the clouds, they

had no reliable way to find the bombers or to return to the tiny island of Iwo Jima because their only navigational aid was a compass.

The remains of many soldiers were never found. Others were buried in temporary graves during the fighting. Depending on the wish of

the next of kin, these were later re-buried in the United States or in the various cemeteries the American Battle Monuments people

care for. The land is deeded to the United States so these men can lie in American soil.

Families coped with the loss in various ways. Many young wives remarried, living the quiet life they expected to live before tragedy

struck. But some went on to have prominent positions - one was a safety engineer with NASA, another was a high official in the United

States Department of Education. Parents might fund a scholarship or have their sonís name included on a memorial. Paul Clingman left

school a few credits short of graduation. But those he earned during his commission training made up the deficit. A July 12, 1945 news

item in the Manhattan Republic said:

A diploma of Marine Lieutenant Paul Clingman, a former Kansas State student reported missing last August 16, will be presented to his

mother after commencement exercises July 24. ... Lt. Clingman was reported missing after his plane was lost in a storm off the

United States coast.

An inscription on Clingmanís tombstone reads, "Let not your heart be troubled." But perhaps this July 4 weekend, we might be troubled

just a little. Perhaps we could pause and remember them - remember "our" Robert Paul Aikman to Joseph Zitnik as well as the thousands

of other men and women who died serving our country.