Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - March 1, 2019

The man from the bus

I don’t watch television shows such as “Criminal Minds.” I just don’t want to know about people who kill other people in a

systematic way. But over our holiday break, I was face-to-face with a 100-year-old mystery involving a serial killer.

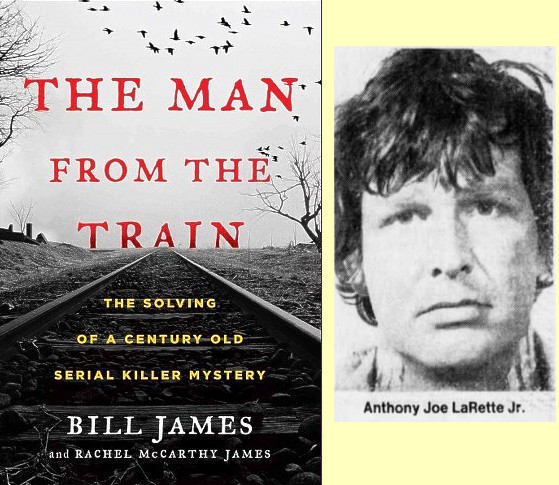

In 2016, I wrote a column containing a reference to the ax murders in Villisca, Iowa. So when

husband Art heard Kansas author Bill James interviewed with his researcher-daughter on Kansas Public Radio late last year, he knew

“The Man from the Train” was a book for me. The Jameses not only connect the dots of multiple murders, including those in Villisca,

with others in the early 1900s, they also stumble upon the killer. Three of the murders were in Kansas - one in Ellsworth, another in

Paola and the third in Martin City, a town in Johnson County.

Art gave the idea to daughter Katie who gave me the book for Christmas.

I was initially uncertain when I unwrapped it because of my aversion to blood and gore. But while we were in Wisconsin over New Year’s,

Art read aloud several chapters. I kept asking him to read more. We completed it on the trip back with me reading to him. The word

that kept coming to mind was “fascinating.”

In the early 1900s, if a small town had a police department, it was often a lone officer with no training. For that matter, there was

little training to be had. There were no crime labs and no DNA testing. Fingerprinting had only recently been uncovered as a tool.

All murders were thought to be motivated by robbery or some sort of grudge. So serial-killer crimes typically went unsolved, although

sometimes people were wrongly convicted and some even executed.

A few days after we were home, Art mentioned the serial killer who had struck here in Manhattan.

I had no recollection of any such crime, but we quickly determined it had occurred when I was working in Costa Rica.

Tracey Miller, 26, the wife of Judge Paul Miller, was repeatedly stabbed in her home during the morning of Nov. 2, 1978, while the

couple’s young daughter was upstairs. When Tracey missed a lunch appointment, a call was made to the judge’s office to see if she

might be ill. The judge’s secretary went to his home and discovered the crime scene.

But by 1978, police and the public were familiar with serial killers, and police forces had resources and training not available 70

years earlier. So when all of the people close to Tracey could be accounted for and no motive could be found, the authorities quickly

realized they were dealing with a crime where the victim had been chosen at random. It would require luck to locate who was involved.

This was so unlike what had happened in those earlier cases. Back then, even after officials correctly assumed they were probably

dealing with a random killing by a stranger and the bloodhounds' noses led them no farther than the local rail line, they promptly

returned to the business of trying to pin the blame on someone local.

In contrast, things quickly settled in Manhattan. While officials were not content with not bringing anyone to justice, there was

little that could be done.

The 1979 Royal Purple, Kansas State University’s yearbook, noted:

... But the year also carried its share of disappointments and tragedies. The hometown atmosphere of Manhattan was shattered with the

news of a brutal murder. The body of Tracey Miller, 26, the wife of Municipal Court Judge Paul Miller, was found in the home Nov. 2,

in the home she shared with her husband and 15-month-old daughter. No murder weapon was found and no suspects were arrested for the

stabbing.

And that was where it stood for ten years.

But Tracey Miller’s murderer had been busy. It is estimated that he was responsible for around 30 murders in states as far west as

Colorado and as far east as Florida. But it was a murder on July 25, 1980 that was his undoing. Anthony Joseph LaRette killed

18-year-old Mary Fleming in St. Charles, Missouri - a neighboring town of St. Louis. He had apparently borrowed a friend’s car and

someone had given a description of it to police. When the friend heard about it, spooked, he called LaRette, who confessed. The next

conversation he had with LaRette was with the police listening in.

LaRette was convicted and sentenced to death. He spent 14 years on death row, longer than any other in Missouri’s history. This was

partly because he began to slowly divulge details of his other crimes, clearing up cold cases. In 1988, he confessed to the Manhattan

murder.

Richard Lee, from the Cole County, Florida prosecutor’s office, was involved in investigating a LaRette murder in that state. In an

article in the Nov. 29, 1995 St. Louis Post Dispatch, Lee said LaRette usually raped his young female victims.

Tony was a serial murderer-rapist who basically traveled all over the U.S. by bus and killed and raped women. ... He’d just get right

back on the bus and leave town.

But unlike the murderer from the train, LaRette did not escape. On Nov. 29, 1995, he was executed.

When first-husband Jerome worked for the Wichita paper in the 1970s, he wrote some of the first stories about local serial killer

Dennis Rader - the BTK or Bind, Torture, Kill - killer. Katie met Rader’s daughter, who was practice teaching in Katie’s high school.

Art’s Aunt Sue worked in prison with Ed Gein, a serial killer known for skinning his victims.

While all these stories are fascinating, they also make me a bit uncomfortable - uncomfortable with how close to home in certain

respects they were.