Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - November 9, 2018

Bells of Peace

Sunday is the centennial of Armistice Day. While many think of Nov. 11, 1918, as the day World War I ended, it was actually the

day Germany agreed to a cessation of open warfare for 31 days beginning at 11 a.m. Paris time.

In popular mythology, the guns fell silent at the agreed time. But many on the front were sure it was only temporary, and fought on.

I can look out my kitchen window and see Fort Riley, where the 1st Infantry Division was formed to fight in World War I. Col. Thomas

Gowenlock, an intelligence officer in the unit, described his experience near Verdun, France on Nov. 11, 1918:

My watch said nine o�clock. With only two hours to go, I drove over to the bank of the Meuse River to see the finish. The shelling was

heavy and, as I walked down the road, it grew steadily worse. It seemed to me that every battery in the world was trying to burn up

its guns. At last eleven o�clock came - but the firing continued. The men on both sides had decided to give each other all they had -

their farewell to arms. It was a very natural impulse after their years of war, but unfortunately many fell after eleven o�clock that

day.

The cease-fire was extended three times. The Treaty of Versailles was finally signed on June 28, 1919 - five years to the day after

the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie - an act considered the war�s starting point. The treaty did not

take effect until Jan. 10, 1920, more than a year after what would be remembered as the end of the war.

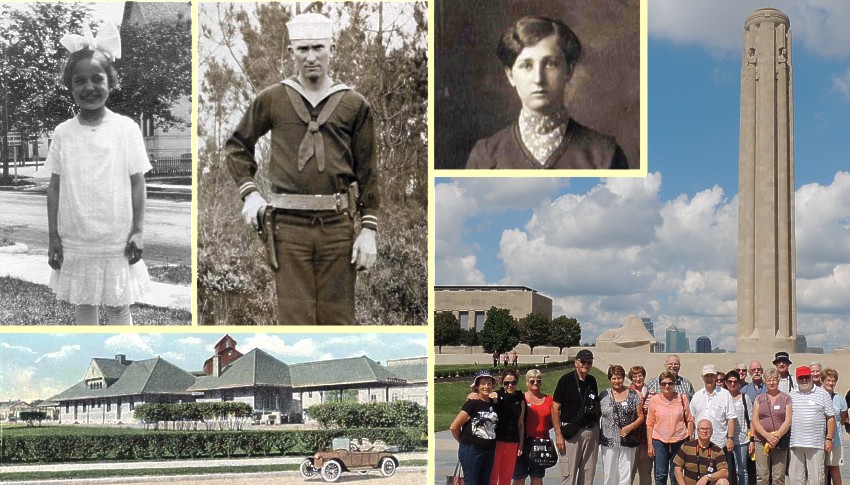

For most people, those details were not that important. Husband Art�s mother Donna remembered Nov. 11, 1918 as a typical Wisconsin day.

Then just a girl of 8, she thought it was strange that she wasn�t in her classroom at Lincoln School on that cool Monday morning.

Instead, she was standing with her parents and her younger sister Arline on the platform at the train depot. Her mother was holding

Donna�s 15-month-old sister Ione. Other family members were there too, but she didn�t remember exactly who. Most likely, her aunt

Ella and her uncle Ed were there because their son Roy was there to get on the train.

Many people were sick. Some people called it La Grippe, while others called it the Spanish Flu. Some died within hours of contracting

it. In eight months, it had spread across the world, killing more people than the war itself.

Those things didn�t make much of an impression on Donna, but the church bells did. Three churches within a five-block area almost at

once began ringing their bells.

What did it mean?

It meant Roy didn�t have to get on the train.

The war was not formally over, but for all those at the station, it was as good as over. Roy would never have to report for induction.

But many others had before, and many served and died.

In summer 2014, our family visited the Verdun, France battlefield. After we returned home, I wrote a column,

�Ghosts of the Great War� to describe what we saw:

We saw remnants of the �war to end all wars� - trenches, barbed wire, forts and cemeteries with row upon row of grave markers.

We stopped at Fort Douamont, the largest and highest fort on the ring of 19 large defensive forts that had protected Verdun. More than

16,000 French soldiers are buried in its cemetery, and the Douamont Ossuary holds the jumbled skeletal remains of some 130,000 French

and German fighters.

After the war, Kansas City was thought to be a good place for a national memorial because so many of the men had funneled through

the city�s Union Station on their way to waiting ships in the East. The November 1921 groundbreaking ceremony for the Liberty Memorial

was attended by more than 100,000, including then-Vice President Calvin Coolidge and Allied commanders U.S. Gen. John �Jack� Pershing,

British Admiral of the Fleet David Richard Beatty, Lt. Gen. Jules Jacques of Belgium, Gen. Armando Diaz of Italy, and Marshal Ferdinand

Foch of France.

It was the first time after the war that the five commanders were together in one place. Future President Harry S. Truman, a veteran

of the war, was chosen to present flags to the commanders.

Friend Barbara Hart�s mother Lily Mellies, then a young secretary in Kansas City, was also there. Barbara recalled her mother saying

she was thrilled to attend such a historical event. Lily would later marry World War I Navy veteran Daniel Roenigk, who served with

the American Expeditionary Forces in France.

The bell used for the 1921 groundbreaking ceremony was originally located at one of the federal buildings in downtown Kansas City, and

had been rung daily by the Daughters of the American Revolution during U.S. involvement in WWI. It was also tolled 11 times at 11 a.m.

on Nov. 11, 1926, during the dedication of the Liberty Memorial.

The first Armistice Day for �The Great War� was celebrated in Britain in 1919. Since 1954, we in the U.S. have celebrated Nov. 11 as

Veterans Day to honor all men and women who have served in the U.S. military. No apostrophe is used as it is not a day that �belongs�

to veterans; it is a day for honoring them.

This Sunday, the 11th day of the 11th month, the bell at the Liberty Memorial Tower, now part of the National World War I Museum and

Memorial complex, will again ring at the 11th hour to mark the centennial of the armistice. Celebrations are planned at other

locations as well.

So on Sunday morning, pause and listen carefully around 11 a.m. You just may hear a nation remembering.