Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - March 16, 2018

Tinkering with time

I’m a big fan of “Star Trek,” “Star Wars” and other science fiction shows that explore our relationship with time and

space. Just a week ago, I saw the newly-released “A Wrinkle in Time.”

But time problems are often more annoying than fascinating. Europe is currently grappling with one that comes from a very

small error - less than a percent of a percent. It’s an error that could soon come to the United States, too.

Prior to the exploration of the oceans, few people had the need for accurate time. A sundial was good enough for daytime

activities, and nights were for sleeping. But sea travel was problematic. The constellations could tell a mariner how far

north or south the ship was. But because stars appear at the same point in the heavens at different longitudes at different

times, if the navigator didn’t know the time, he couldn’t determine his east-west position. Then in the 1600s, a spring balance

was invented that produced a clock that was accurate to within a few minutes in a month. Long sea voyages were then less

dangerous, and ocean travel took off.

A similar problem afflicted railroads in the 19th century. Every town set its own clocks, typically by the approximate local

noon. This raised havoc with scheduling. Laws were passed late in the century in England and in the United States to establish

a uniform time for entire regions.

Then Daylight Saving Time threw another wrinkle into the system. When we switched to DST last Sunday, daughter Mariya said,

“We should just leave it this way year-round to stop messing with people’s rhythms.”

I agree. I felt “off” the whole day and then discovered I was greatly in error on a related time problem. My memory was of

writing a previous column about DST and I didn’t want to write another too soon. But after searching, rather than being a

couple of years ago as I had thought, it was actually published on Oct. 28, 2005! Talk about being in a time warp!

In that column, I explained that DST was introduced into the United States during World War I to save energy and was repealed

after the war because it was unpopular. During World War II, the government again required using DST. Afterward, states and

communities were allowed to choose on their own whether to use it and when to start and stop.

It was a mess! The broadcast and transportation industries had to publish new schedules every time a state or town began or

ended DST. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 was passed to help eliminate this problem, and it has since been tweaked twice. In

1986, the start date was moved from the last Sunday in April to the first Sunday in April. In 2007, it was changed again to

the second Sunday in March and extended to the first Sunday in November.

Some cultures are more casual about time than we are. In Latin America, the attitude is that “mańana” - tomorrow - is just

as good as today to get something done.

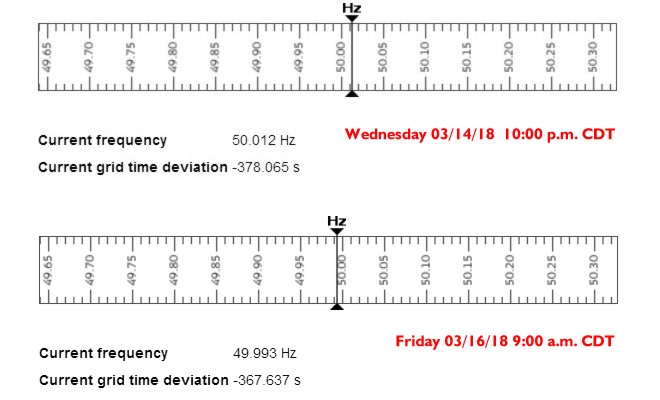

But the recent problem of people moving more slowly in Europe is of a very different nature. According to the March 8, 2018

article - “Clocks Slow in Europe? Blame Kosovo-Serbia Row” - in nytimes.com, the slowdown began in mid-January, and since

then, some clocks in 25 countries have been steadily losing time. According to husband Art, an electrical engineer, all the

articles show a certain lack of understanding of the situation. So, I asked him to explain.

He said in U.S. power systems, ideally the electric current changes - first flowing one way and then the other - 60 times

every second (60 Hertz). In Europe, the figure is 50 times a second. All older electric clocks have a small motor that

rotate in step with these alternations. Gears reduce the speed such that the second, minute and hour hands move at the desired

pace.

But the actual alternation rate is determined by how fast the power plant generators turn. When people turn on air conditioners or

stoves or lights, the generators slow because of the increased load. Late at night, when the loads are small, they naturally

speed up. The people who manage the system watch what is happening and trim the generators so the long-term effect is zero.

That way, while our clocks may at any time be fast or slow by a few seconds, the electric plants compensate by going in the

opposite direction until clocks give the correct time.

In January, a large generator in Kosovo of the former Yugoslavia was taken off line - some stories say for maintenance, while

others say it was because of customers who were not paying for the energy they were consuming. This deficit increased the load

on those remaining in the European grid and those generators slowed ever so slightly as a result. But the Serbian

administrator in charge of balancing the portion of the grid containing Kosovo did nothing. The decrease was slight - a change

from 50 Hertz to an average of 49.996 Hertz. But that slight decrease accumulated and, by early this month, clocks that rely

on the power line were running about six minutes slow.

Art said most clocks today depend on internal time-keeping devices that do not rely on the power line frequency. Others, like

cell phones in the United States, get the time from radio signals that are connected indirectly to an atomic clock operated by

the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Colorado. NIST's clock is accurate to less than one second of error in

300 million years.

That’s good enough for me!

There is a tentative agreement in Europe to solve its problem, but in the U.S., petitions have been filed to relieve our

electric suppliers from controlling the average frequency. If these are granted, our old clocks may wander fast and slow and

all of us may be forced to tinker with time to correct them.