Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - March 9, 2018

“The Glitter and the Gloom”

It was billed as an evening to experience the sights, smells, tastes and feelings of the 1880s in Manhattan, Kansas - the time we often call the Victorian Era.

The U.S. experienced rapid economic growth, swift industrialization, and an influx of millions of impoverished immigrants.

Mark Twain wrote a novel about the times. In it, he satirized the era as one of social problems masked by a thin veneer of wealth for a few. While Andrew Carnegie,

Andrew Mellon and J.P. Morgan were getting rich, Jane Addams, known as the “mother” of social work, co-founded Chicago’s Hull House - a settlement that provided

social services and education to working class immigrants and laborers. An alternate name for that period comes from the first part of Twain’s book title:

“The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today.”

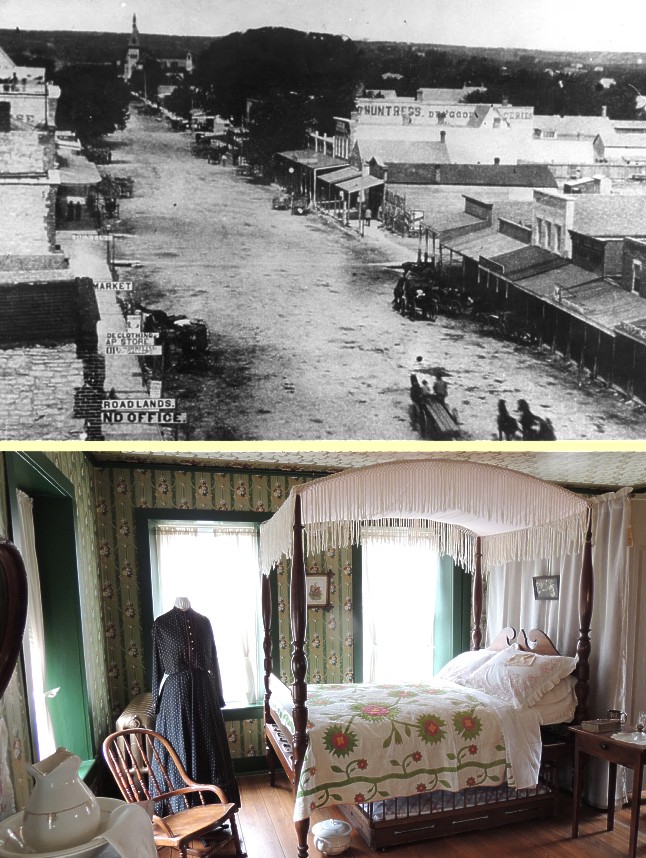

In 1880, Manhattan had a population of 2,104, about four percent of the current number of residents we have in the city we now call “The Little Apple.” The county

was home to 10,420.

A group of 300 African-Americans had migrated to Manhattan. They were part of the Exoduster Movement or Exodus of 1879, the first general migration of African

Americans to Kansas following the Civil War.

Most people heated their homes with coal, cooked with wood, and used kerosene lamps to see at night. But things were changing. Milestone events included an

organized fire department in 1884, a water system in 1887 and electric power in 1889. This latter improvement led the following year to incandescent

lighting on Poyntz Avenue, the primary business street. By 1894, there was city-wide phone service, and a sewer system was installed in 1899.

Most people still walked or traveled by horse on unpaved streets. Manhattan was served by three railroads: the Kansas-Pacific, which in 1880 joined the

Union Pacific, the Leavenworth, Kansas and Western (LKW) and Chicago-Rock Island-Pacific (CRIP).

The event where I learned about what life was like in the Gilded Age was called “Glitter and Gloom” and was presented by Riley County Historical Museum staff

members in the Manhattan Public Library. It was one in a three-part series - “Time Travel to the 1880s” - to commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Wolf House,

a Manhattan home built of native limestone in 1868. It was used as a boarding house for many years and is now a museum.

In 1880, there were seven physicians and three druggists in Manhattan, but people still used home remedies and tonics, believing they were good for anything

that ailed them. This is understandable as most physicians had less than a high school education.

As part of the “smells” portion of the program, small bottles of Mentholatum and asafoetida, popular home remedies of the era, were passed around. The

Mentholatum was familiar and almost comforting because I remember Mom rubbing it on my chest and then covering it with a warm towel when I had colds and coughs.

Asafoetida (asuh-feh-ti-da), a resinous gum from an herb native to Iran and Afghanistan and a relative of celery, was used as a topical treatment for abdominal injuries and put

into bags to ward off diseases. It was a new experience. Sometimes called devil’s dung, it had a smell I described as "fetid." I didn’t linger long testing its scent.

Many people then believed they could be cured by mineral water. Blasing’s Springs, seven miles southeast of Manhattan, advertised that its mineral water could

cure “torpid liver, lung affections, female diseases, syphilis, rheumatism, sore eyes, chronic stomach diseases, dyspepsia, dropsy ...” and many other

afflictions. It did contain sulphur that acted as a laxative. After imbibing, a person’s liver might still be torpid, but other things would be quite active.

People flocked to Blasing’s Springs in such numbers that a hotel was built to accommodate them.

In 1880, Kansas State Agricultural College (KSAC) - now Kansas State University - had 276 students - about one percent of its current size - and 11 faculty members.

Tuition was free, except for a $3 lab fee for those taking chemistry. Every morning, all students were expected to take part in calisthenics.

George Fairchild was the college’s president. Anderson Hall, now the chief administration building, was completed in stages during his tenure. The campus grounds

included flower gardens and greenhouses used to grow vegetables and fruit trees.

Nellie Sawyer Kedzie, an 1876 graduate of KSAC, taught domestic science at the college from 1882-1897. She was promoted to full professor in 1887, becoming the

first female department head at KSAC. She lobbied the Kansas legislature to build a domestic science hall - the first in the nation - which was eventually

named Kedzie Hall in her honor and is the building in which I work.

We honored Kedzie in a different way. Our sense of taste for the era came into play when we sampled tea and ate biscuits, the latter made from an updated

version of Kedzie’s personal recipe.

I have to say the program was more than a little fun. Seeing the old photos, hearing the descriptions, smelling the Mentholatum and asafoetida, and tasting the

tea and biscuits really made me feel as if I had traveled back to the “glitter and gloom” of 1880s life in Manhattan, Kansas. Still, I think I’m happy to be living now.