Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - May 12, 2017

Connected by a thread - Part II

Last week’s column, “Connected by a thread,” was the first of two seemingly unconnected

stories. It was a bit about the life of Kansas native Lt. Gen. Richard Seitz, a World War II war hero, and how his

papers were donated to the special collections area of Kansas State University’s Hale Library. Now for the second story and

the connection!

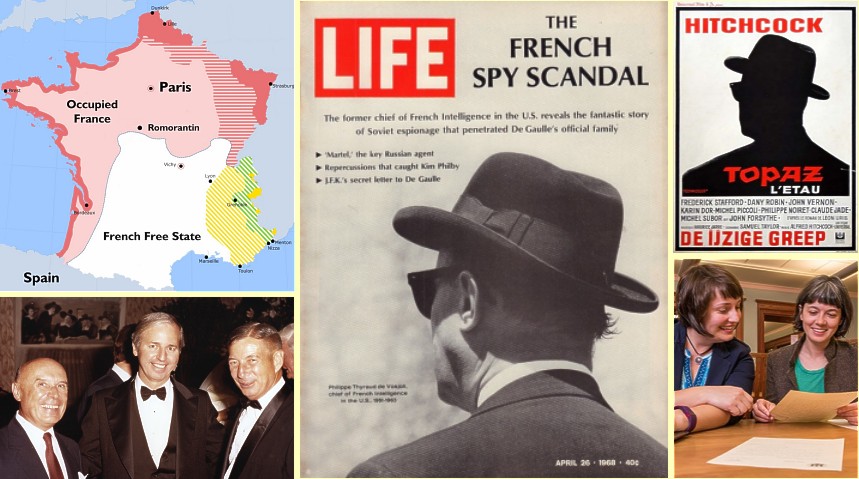

Frenchman Philippe Thyraud de Vosjoli (vo-jo-lee) was 18 when France was defeated by Germany in June 1940. Germany didn’t

want to expend the resources needed to occupy the entire country and so split it into two zones. The northern and western

areas remained under German occupation. The remainder, “The French Free State,” was governed by a nominally free regime.

Paris, part of the occupied zone, was where de Vosjoli worked as a law apprentice in a firm with many Jewish clients. One

of them, a Mr. Meyer, approached de Vosjoli about escaping to the free state where he was less likely to be caught. Romorantin,

de Vosjoli’s hometown, was about 120 miles south of Paris and situated five miles north of the Cher River, which separated

the two zones.

One weekend, the two men bicycled from Paris to Romorantin. De Vosjoli knew the rigid routine of the German soldiers

monitoring a trestle bridge over the river.

Attorney Alan Greer, a friend of de Vosjoli, said “The Germans patrols went out at 10 p.m. and 2 a.m.”

Meyer and de Vosjoli followed 100 to 150 feet behind the earlier patrol as it departed the occupied zone.

“The sound of the Germans’ hobnail boots covered the sound of Philippe and the French Jew,” Greer added.

De Vosjoli then waited for 2 a.m. patrol, crossed the bridge and then bicycled back to Paris.

Meyer apparently wrote his friends. “... Philippe suddenly found himself running a sort of underground railroad for

small parties of Jews using the same route he’d used with Meyer,” Greer said.

But one night while waiting for the 2 a.m. return time, a man approached and asked for help sneaking into the occupied

zone. De Vosjoli realized the man was an Allied spy. It was clear too many people knew what he was doing.

So he walked to the Spanish border, crossed Spain and made his way across the Mediterranean Sea to Algeria - a French

colony. An ardent anti-communist and French patriot, he joined the French resistance and conveyed documents and

correspondence between French President-in-exile Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill and other World War II figures.

After the war, de Vosjoli joined the French Intelligence service. In 1951, he was stationed in Washington, D.C. as the

French liaison to the Central Intelligence Agency. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, he helped monitor the Soviet presence

in Cuba, sharing information with the CIA.

In 1961, Anatoliy Golitsyn, a high-ranking official of the KGB, the Soviet counterpart of the CIA, defected. De Vosjoli

had access to the information Golitsyn was providing and heard that Soviet spies had infiltrated the French government to

the highest level, including de Gaulle’s cabinet. De Vosjoli suspected Golitsyn was lying in the hope of making himself seem

more valuable, but de Vosjoli passed the information along for his superiors to check.

But the response struck him as curious. His reports were ignored and he was told to quit wasting his time.

In late 1962 or early 1963, de Vosjoli was ordered to organize a spy network to obtain U.S. atomic bomb secrets.

He refused. Not long after, he was ordered to return home. But before leaving, he was told by a friend that his

reports were ignored because de Gaulle feared such revelations would be so embarrassing they might push him from power.

The friend advised de Vosjoli not to return as he could be the victim of an assassination, something the French government

had been doing quite a bit of.

De Vosjoli resigned and stayed in the United States, fearing for his life. When President Kennedy was assassinated, de

Vosjoli was worried it might be a part of a bigger plot. So he bought a car, and along with his family, fled to Mexico

where they stayed with a friend. He began writing a book about his experiences. It was there he met author Leon Uris. De

Vosjoli and his family then moved to south Florida.

In 1967, Uris published “Topaz,” a thinly-disguised account of de Vosjoli’s life, and sold the movie rights to director Alfred

Hitchcock. De Vosjoli met Greer as a member of a team of lawyers who pressed a successful suit against Uris over unpaid

royalties. Greer and de Vosjoli became friends.

De Vosjoli had kept some papers from his war years. He had been ordered to destroy them, but had not, owing to their

historic nature. He decided to give them to Greer. De Vosjoli, who had bcome a U.S. citizen, died of cancer on April 25, 2000.

When his father-in-law Richard Seitz, a man Greer greatly admired, decided to donate his papers to K-State, Greer began

to think about doing the same with the de Vosjoli papers.

After doing so, the course French 720: “Translating the ‘Freedom Papers’: Charles de Gaulle and WW2 Correspondence” was

created. To date, seven undergraduate and three graduate students have worked on them, supervised by professors Melinda Cro

and Kathleen Antonioli. Antonioli explained:

There are 27 letters in the archive, 12 of which are in French. Several of the letters are unpublished, and do not

appear in de Gaulle’s collected correspondence, and none of them have ever been translated into English. ...

Antonioli said both students and teachers were unfamiliar with related war-time details. So it was necessary to study

these aspects as well and pair them “with de Gaulle’s particular writing style, to ensure that they would be able to produce

faithful, useful, readable translations of the letters.”

So Alan Greer proved to be far more than the Wikipedia curator Crawford mentioned in last week’s column. He was a

filament in the web that brought these historic items to K-State.