Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - January 20, 2017

From creepy to intriguing

When a loved one dies, it is comforting to keep some part of the person close. In countries such as Indonesia, the

mummified remains are sometimes kept in the family home and even dressed to celebrate special occasions as if the person

was still alive. Being unfamiliar with such a practice, I find it a bit creepy. I’ll opt for remembering a loved one by

displaying a photo or keeping some object connected with that person such as a pocket watch or a piece of china.

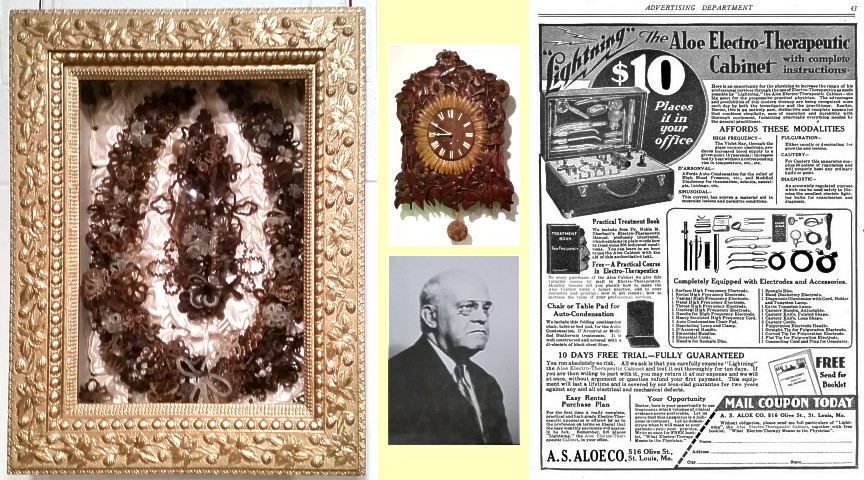

But as recently as the Victorian era people sometimes chose to keep a part of the physical remains of loved ones.

Some families had small bowls called hair receivers where strands of a person’s hair were routinely saved. Upon the

person’s death, that hair was formed into a figure such as a flower.

A family memorial was sometimes created by grouping these small figures into the shape of a horseshoe, with the open

end pointing upward to symbolize the passage of the person’s soul to Heaven. The hair figure of the most

recently-departed was placed in the center. It would then be moved to the side when the next family member passed. These

memorial hair wreaths were mounted on the wall or set on a table, protected by a glass covering.

I was reminded of this practice recently at the Riley County Historical Museum. It turned 100 last fall, and

the staff are commemorating the occasion with a year-long exhibition.

In addition to the hair wreath, I saw a section of the original seating from Manhattan’s Wareham Opera House, a

hand-carved sunflower clock made from local walnut and osage-orange wood for Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition

and a gavel used during the first meetings of the Manhattan Town Association. Of course, there were also more common

museum items, such as Civil War uniforms, feather hats, saddles, a 1920s swimsuit and a glove/handkerchief box from the

old Sikes Store in nearby Leonardville.

Being half Swedish, I was drawn to a traveling trunk from the Floberg family. The wooden trunk, addressed to Christina

Floberg, was shipped to Olsburg, Kansas, “Nortamericka” in the 1870s from relatives in Sweden. Jonas and Catharina

Svensdotter Johansson immigrated to New York City in 1864. In 1866, the couple and their two children homesteaded near

Olsburg, Kansas. In 1872, Catharina changed her first name to “Christina” and the couple changed their last name to

“Floberg.”

Local historical objects like the trunk were first stored in the city park’s Pioneer Log Cabin, dedicated as a museum

in October 1916. In 1957, the museum moved to a hand-dug basement under Manhattan’s City Hall and remained there until

the current building was dedicated in 1976.

The museum has a collection of about 85,000 objects, 4,500 books and monographs, 10,800 cubic feet of manuscripts

and archives, and 27,000 photographic negatives and images. The staff also oversees eight historic properties and, in

partnership with the Kansas State Historical Society and the Riley County Historical Society, operates the Goodnow House

State Historic Site.

Among those collected items, another that caught my attention was the “Aloe Electro-Therapeutic Cabinet.” Its maker

claimed it treated high blood pressure, lesions and paralysis. The museum’s cabinet belonged to Dr. William Clarkson,

who started his practice in nearby Keats in 1900, traveling by horse and buggy to see his patients.

I asked Allana Parker, the museum’s curator of design, what other unusual objects were unearthed when preparing

the centennial display.

She mentioned the Nestle permanent hair wave machine. In 1905, German hairdresser Karl Nessler invented a machine

that used an electric heating mechanism and a forming agent, such as a mixture of cow urine and water, to achieve a wavy

hairstyle. She said this “spiral heat method” used 12 two-pound brass rollers heated to 200 degrees. The treatment took up

to six hours. The hot rollers were kept from touching the scalp by a complex system of cables with counter weights suspended

from an overhead chandelier mounted on a stand.

“Early tests done with his wife resulted in her hair being completely burned off,” Parker said.

After Nessler made improvements, he moved to New York in 1915 and changed his name to Charles Nestle. By 1927, Nestle

owned several hair salons that used his permanent wave machine. One of the devices found its way to a beauty shop in

Leonardville.

Visitors can see this special exhibit, which took six months to create, during the museum’s regular hours, 8:30 a.m. - 5

p.m. Tuesday through Friday and 2-5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. But there will be a special open house from 2-5 p.m. Sunday,

Jan. 29, which coincides with Kansas Day.

“The open house will feature some of the secret stories about objects in the centennial exhibit,” said Cheryl Collins,

director of the museum. “We are planning to have staff members pick out one of the interesting objects in the exhibit and

tell a little bit more, make connections with current events, people or other objects in the exhibit.”

Hmm. Secret centennial stories: just the thing for a history fanatic like me!