Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - Nov. 8, 2013

A small town; a big story

It's quiet here. If it weren't for the trucks traveling to and from the local grain elevator, a stranger may not see a

person for some time.

And strangers too are rare. It's not a place where people are likely to arrive by taking a wrong turn. The village

straddles a road off a road intersecting a highway that winds through mile after mile of open prairie. It's in the

heart of the American heartland - a place as far from her bordering oceans as it's possible to be.

Yet this little village once did something quite extraordinary. And the story of what it did was heard by Americans

from coast to coast and the country's soldiers overseas. It's a story that connects the distant oceans, President Abraham

Lincoln, Yale University and the battle-weary Iron Men of Metz.

It's also the story of how good humans can be.

A possible starting point in the tale might be Ebenezer Morgan's wish. He was a whaling captain - the first to

plant our flag on Alaskan soil after Russia signed her rights to that land over to America. After making his fortune

sailing the oceans, he left Massachusetts to pursue his dream of owning a ranch on the landlocked prairie. Shortly after the

Civil War, he and others settled what became Morganville, Kan.

The Carson family settled nearby. A chance meeting near their home in Illinois with a lawyer convinced them the West

was the place to be. That lawyer was Abraham Lincoln.

The years passed with nothing particularly unusual happening in this small village of a few hundred people. When

the U.S. was drawn into World War II, like other places, Morganville sent men off to serve. Perhaps the folks at

home read articles or listened to radio reports in December of 1944 when, after three months of fighting, American

soldiers captured the German stronghold of Metz, France. The price of victory was paid with terrible losses.

But other costly battles would follow. Some of those soldiers had almost no rest before marching northward to

relieve their brothers fighting to stay alive in the Battle of the Bulge. Later still, there was Japan to deal with.

It's unlikely many people in Morganville thought again about the actions taken by the soldiers whom the German commander

called "The Iron Men of Metz."

In 1948, three years after the war, Morganville's citizens heard of the desperate condition Europeans faced. The

war's destruction had been followed by unusually cold and snowy winters. Prompted by the local Methodist minister,

the town decided to adopt a war-battered sister city. It wanted to help a similar-size community of farmers like

itself. It selected F�ves- a French village located six miles northwest of Metz that had been devastated by American

shelling.

After much brainstorming about how to generate money, these Kansans decided they would produce a pageant. Velma

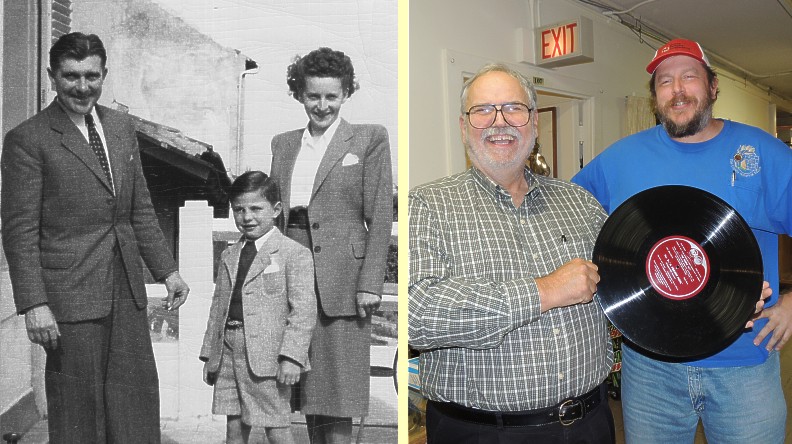

Carson, the granddaughter of the man who had spoken with Lincoln, wrote the pageant script. She knew

what she was doing for she was college-educated and had worked for years in the East, earning a living as a writer.

The pageant's original cast of 30 grew to 150 - more than half the town's population. The theme was world peace and

it told the story of how Morganville's settlers had come from many countries. Costumes came from around the world, some

acquired as hand-me-downs from settling families, while others were the souvenirs of returning servicemen brought from far-away

places. Morganville was not alone in its efforts to raise money. Other towns and cities adopted sister cities too. But

the next smallest was four times larger. Most collected money by more conventional means, such as asking for donations.

Morganville's zeal drew attention. On Aug. 27, 1948, the night of the pageant, between 2,000 and 3,000 people arrived

to see it. By late September, a stream of supplies such as powdered milk and clothing for children, shoes for adults,

colored pencils for the F�ves school and seeds for village gardens began flowing from Morganville.

Letters of appreciation came in return. Children in Morganville who had donated coats with their names and addresses

pinned to the inside acquired pen pals.

In 1950, Yale graduate and its first chaplain Elmore McKee produced 13 radio broadcasts about Americans who didn't wait

for their government to solve problems. The Morganville story was one he chose. The NBC network aired it coast to coast at

6 p.m. on Dec. 23 of that year. McKee called it "A Prairie Noel." Five years later, he wrote a book called "The People Act."

Morganville's story was Chapter 7.

Sixty-five years have now passed. F�ves' proximity to prosperous Metz has fostered growth. It has expanded several times

and has nearly 1,000 citizens.

But modern advancements have not been so kind to Morganville. Roads that permit easy travel to larger places and

agricultural changes that allow fewer people to do far more than was possible in 1948 have taken a toll. The village now

has fewer than 200 people.

And people forget. Last July, a Morganville couple stopped to see if husband Art and I needed help as we stood near the

curious concrete amphitheater at the edge of Main Street. After assuring them we were fine, I asked if they knew what had

happened there nearly 65 years earlier. They were unaware that one warm summer night so many years before, there had

been a performance that literally touched the world.

But there are some who remember. A few remain who were in the pageant, perhaps as a Swedish or Spanish dancer or a member

of the town orchestra or as a singer. Others helped with serving the turkey dinner, giving pony rides to youngsters or scooping

ice cream. There are still a few who joined in the square dance that marked the end of that evening.

Even some not-so-local people remembered. Richard Parker was one of them. He became a three-time U.S. ambassador to

Algeria, Lebanon and Morocco and had one-time postings to Australia, Israel, Jordan and Egypt. When he was recognized in

2004 for his lifetime contribution to diplomacy, he was asked about some of his experiences. In regard to working for

UNESCO, he said:

"... the most exciting thing I did was to witness a festival celebrating the adoption of a town in France by a

little town named Morganville, not far from Manhattan, where the university was. That was a great event. Everyone came

from miles around and people performed on a stage set up in a vacant lot. It was a very rewarding grass-roots

experience."

But the story isn't quite over yet. Between Christmas and New Year this year, G�rard Torlotting and his family will

be visiting Morganville. Mr. Torlotting was in the textile business for many years before retiring. After his working

years were behind him, he and his wife traveled to many places. So why would he choose to come to Morganville when

there are so many attractive sights in easy-to-reach large cities? It is because as a boy of 6, it was his hometown where

the Morganville items were sent. F�ves is where he grew up.

When Velma Carson composed the letter asking her hometown to be paired with a community in Europe, she wrote, "We are blessed

with a world-minded minister and lots of bright people that would rather be farmers than famous." Whether they desired it

or not, briefly, they were famous.

Today, Morganville is just another small and quiet community. It's the kind of place a stranger could be forgiven for

concluding, nothing ever happened here.