Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - June 1, 2012

It’s up to us

As husband Art and I drove southwest along the country road between the village of Holme and the hamlet of Conington, a small airplane practiced take-offs and landings at the airstrip to the north. Other than the sound of the plane's engine, little would cause a visitor to believe this area of northeastern England had ever been anything more than the sleepy home to these two rural farming communities and the lush farmland that lay between them.

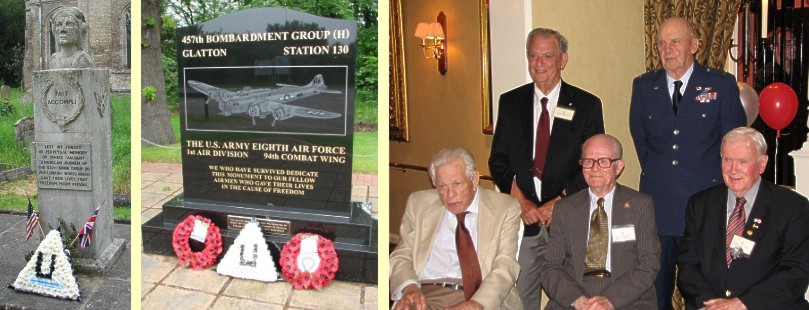

The Conington church is virtually "disused," as the British say, and the lane leading to it is blocked with a locked wooden gate. Yet on the edge of the cemetery to the north, there is one clue that things are not completely as they may seem. It is the bust of a young man. The stone is weathered, yet is not of great age and there is something different about the head. Still, few would negotiate the tall grass covering most of the headstones to get to it.

Another clue is a weathered black structure the size of a large fire watch tower on the west side of Conington. Its purpose is not obvious, but it also is disused.

A few miles to the north, a road heads west from Holme. Several miles from the village, a wide concrete surface stretches northward from the roadway for a hundred feet or so and then stops abruptly in a farm field. On the other side of the road opposite the concrete pad, a small trail leads southward into the farmland. Neither appears to have any reason for being there.

But hard to miss are two flagpoles - one carrying the Union Jack and one the American flag - flanking a large black marker at the western edge of Conington. The message on the stone is clear. The marker's face is polished to a mirror smoothness. An image of an airplane is etched into the surface, and the words on it explain that this quiet place was once a bustling piece of America in the heart of the British homeland.

Sixty-nine years ago, Conington began its transformation into Glatton Air Base, also known as Flight Station 130. At the end of 1943, the engineers turned it over to the Army Air Force and it became the home of the 457th Bomb Group.

In early 1944, the 457th began bombing runs over Hitler's Fortress Europe. The group had four squads and each normally put up 12 planes for every mission. Each plane carried 10 men who would be called into action before the first light of dawn. Takeoff time would be near daybreak and each man hoped he'd see that church tower a few hours later on a safe return trip.

And for every man to take to the air, many others stayed behind. Some refueled and repaired the planes and loaded the bombs. Others cared for the injured, gave mission briefings, guarded the base's borders, cooked, painted and did all the other things a small city needs to function.

The unusual bust in the cemetery is of an airman in his flight helmet. The black structure was the base's water tower. The road connecting the two villages was once a runway. Two other strips are still being used by local pilots. The concrete pad at the road's edge was where the bombs were stored until loaded. The small path was used to transport them to the waiting aircraft.

Then, less than three years after it all began, the base was abandoned. Germany was defeated and America refocused on the war with Japan. For a short time, Glatton Air Base was an important place, but that day had passed. The trees and grass and weeds eventually reclaimed what they had surrendered just a few years before.

But while nature has covered most of the physical remnants of the air base, people today are doing their part to safeguard the history of the 457th and its members. They not only have erected markers and plaques, but they also are gathering mementos and photos, recording individual histories and participating in 457th reunions.

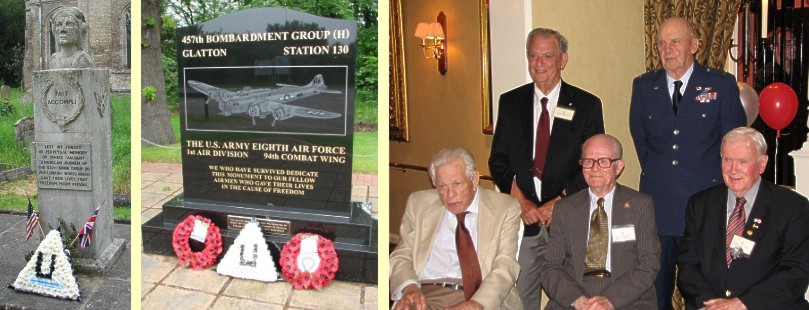

On the evening of our visit to Conington, about 50 people attended the group's reunion in Peterborough, England, a few miles north of the old base. Art and I were there because his Uncle Pete and his former boss John Lindholm were part of the 457th. This year, only five veterans attended; the rest were family members, friends, historians and locals grateful for what those veterans and their comrades did so many years ago.

James Bass, one of the five and a B-17 radioman, said to those assembled, "We are the past. You are the link to the future."

And so we are. Now it is up to the younger generations to either preserve a piece of this once crucial part of our past or, like the tower, the concrete pad and the stone airman silently gazing over the fields, to let it all become just a curious artifact in a sleepy little hamlet in the quiet English countryside.

Left: The airman monument in the church cemetery; middle: memorial on the west side of Conington; right: the five veterans at the 457th reunion.

Comments? [email protected].

Earlier columns from 2012 may be found at: 2012 Index.

Links to previous years are on the home page: Home