Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - April 20, 2012

Fishing for the past

While journalists like to believe they perform a community service, those who don't watch the bottom line soon have to find another endeavor to put food on the table. So it isn't surprising when considering who in the 19th century had money, could read and were in the majority, that newspapers and magazines were produced by whites for whites. As the black community grew in literacy, numbers and wealth, here and there, a few newspapers and magazines produced by blacks and largely for blacks began to appear. Yet little changed in mainstream publishing.

As a white youngster raised in largely white rural Kansas, I was completely unaware of any of the publications from the black community - including one that was right under my nose. But something that happened two years ago changed that for me and also led to an event on the Kansas State University campus a week ago. While looking for materials for the 2010 centennial celebration of my department, I came across several boxes and file folders of largely forgotten documents, photos, publications and more that had been stacked here and there in Kedzie Hall. Inside a closet, I found an old wooden file cabinet. When I looked inside, I discovered it was filled with black press materials from the 1960s and '70s.

Being busy with organizing the celebration and wanting to make certain nothing would be lost, I volunteered to be the unofficial "keeper" of the department's history. Soon boxes and file folders were squirreled away in my office.

I knew Bob Bontrager, a former faculty member and two-time interim department head, had taught a course called "The Black Press," in the 1970s. It was one of the few classes in the United States that focused entirely on African-American publications. I e-mailed Bob and he confirmed they were his.

The situation needed a professional, so I called Cliff Hight, the K-State archivist. Last fall, he came and carefully lifted the publications from the file drawers into archival boxes and carted them to Hale Library.

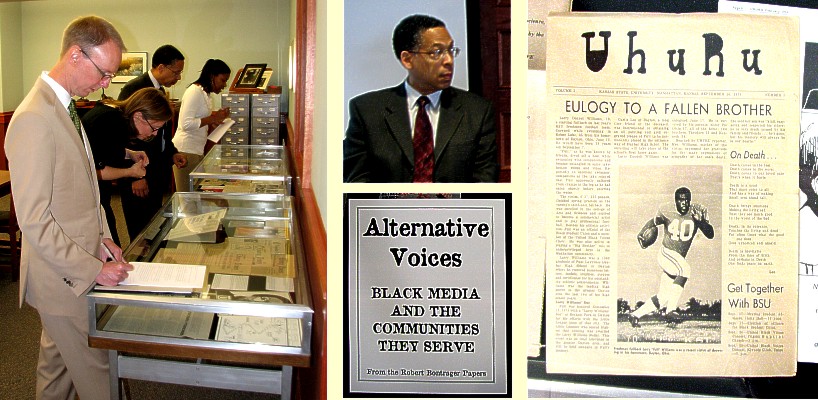

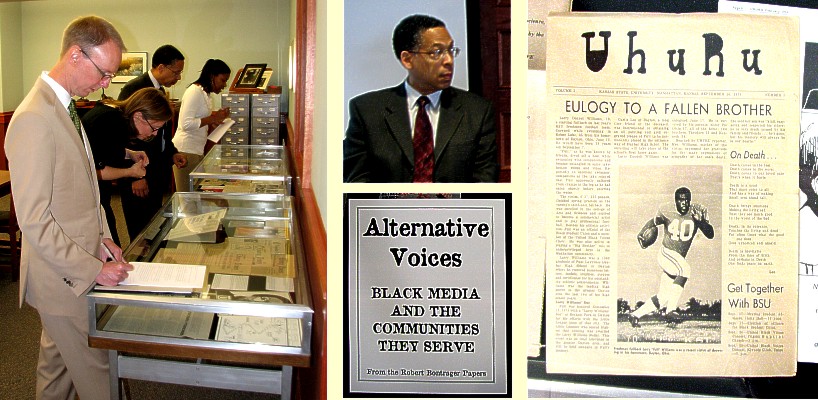

Last Friday, the department and the K-State Archives showcased some of those publications in an exhibit titled, "Alternative Voices: Black Media and the Communities They Serve." Cliff and his staff had on display 15 of the 165 titles in the collection. Among the publications on display were "MsTIQUE" magazine, "The Topeka Ebony Times" and "The Black Panther."

But it was "Uhuru" that caught my eye. It was a newsletter published by K-State's Student Publications from 1970-1975. That was a time when I was a student in journalism and worked at Student Publications, yet I didn't recall the newsletter. Its first editor was Frank "Klorox" Cleveland, who ran for student body president in 1970 and lost in a runoff to Pat Bosco, K-State's current vice president of student life.

In a noontime event hosted by the library, Hight told the audience that opening the drawers was "like opening a treasure chest."

Lewis Diuguid, a Kansas City Star columnist, author and facilitator of diversity workshops, was a guest speaker at the event. He discussed the importance of black newspapers in U.S. history. He mentioned three in particular - "Freedom's Journal," first published in 1827; Frederick Douglass's "North Star," first published in 1847; and the "Kansas City Call," started by Chester A. Franklin in 1919 and still published today.

Diuguid said those papers and others, such as "The Chicago Defender" and "The Pittsburgh Courier," provided local, regional and national information on current events and contained editorials condemning, at first, slavery, and then lynching, the Ku Klux Klan, police brutality and other injustices.

Diuguid said the influence of the black press was particularly felt in the migration of blacks to the North from the 1890s through the 1970s. During that period, Southern whites didn't want African-Americans learning about opportunities in the North, so they confiscated and destroyed the black newspapers printed in the North. But the papers' owners didn't give up. They "went underground" to get the papers distributed. They enlisted Pullman porters, most of whom were black, to carry their papers onto trains and to drop bundles into Southern fields, where African Americans picked them up and distributed them to family members and friends.

Through the years, the black press also pressured for equal treatment in the military, pushed for civil rights and advocated for equality in education, housing and employment.

Diuguid said there is still a need for minority publications because mainstream media do "such an abysmal job" of covering minority communities.

Later, while walking back to my office, I thought about Bontrager's collection and how pleased I was that it had joined other Hale Library resources. But I'll confess there was more. I have a hunch that the enjoyment a history nut receives rummaging through old drawers and files may be similar to what a fisherman experiences. It's exciting to see what you'll come up with - and occasionally you may be fortunate to catch something special.

Left, attendees at the Bontrager paper release studying the displayed papers; middle top, speaker Lewis Diuguid; middle bottom, collection identification placard; right, first edition of the student newspaper "Uhuru." The name is a Swahili word meaning "freedom."

Comments? [email protected].

Earlier columns from 2012 may be found at: 2012 Index.

Links to previous years are on the home page: Home