Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - Nov. 5, 2010

Crane berries!

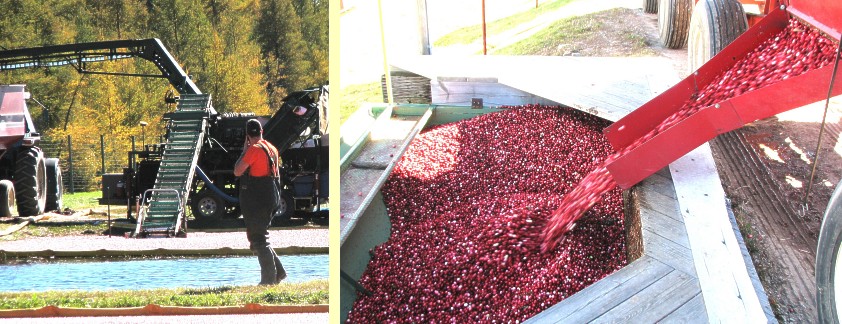

You know Thanksgiving is approaching when ads for cranberries begin appearing on TV - the ones with a couple of guys in waders standing in a flooded bog with the bright red

berries floating around them.

While the cranberry is native to North America, most Americans harbor a misconception about this essential holiday side dish. No, the berries don't grow in water. The bushes are

flooded only to make the fruit easier to harvest.

Another misunderstanding is that most cranberries come from Massachusetts. The well-known Ocean Spray brand name reinforces that image. But 60 percent of the nation's

cranberries are grown about as far from the ocean as you can get in what most of us know as America's dairy land. Wisconsin has been the top cranberry-producing state for 16

straight years and produces twice the amount of the Bay State.

Although our cottage in Wisconsin is located near several marshes, we've always missed the annual cranberryfest and the accompanying bog tours. Yet I've always wondering how

our favorite holiday fruit makes it from the field to dining room table.

But one day this year while husband Art and I were in his home state to winterize our cottage, we stopped along the highway by the Tamarack Flowage operation. When we saw a

school bus moving between the bogs, we concluded someone must be around to explain the harvest process to the children.

After entering the farm, we located a worker who gave us directions to where we'd find Gary Martin, the manager. We met Martin operating a conveyor belt that was delivering

the just-picked berries into a truck. He agreed to answer our questions as long as we didn't mind him stopping from time to time to move the truck as the trailer filled.

Martin said the bog owner has supplied him with a home on the very edge of the beds and he's one of only two people employed year-round.

He explained that cranberry bushes are grown in plots surrounded by earthen dikes. When the fruit is ripe, water is added to the beds and then a mechanical "beater" is driven

through them to break the fruit free from the bushes. More water is then added and, because each berry has three air pockets, they float, allowing the fruit to be corralled or "boomed"

to one end - a process similar to that used to clean up oil spills. A conveyor belt picks the berries out of the water and delivers them to a waiting gravity box - a hopper-like trailer

with a bottom that can be opened.

Once full, the gravity box is towed to the trailer filling station that Martin was operating. The box bottom is opened and the berries flood out onto the trailer-filling conveyor belt. He

said that each trailer held 60,000 pounds of the fruit and the one he was loading when we were there was the ninth he'd filled in the five days since harvest began. The berries are

then taken to a storage area for cleaning.

He invited us to drive along the small roads between the various beds to see the process up close and we accepted his offer.

We watched as a couple of workers drove beaters into a recently-flooded bed. Immediately, the bright red berries bobbed to the surface, a scene made more striking by the deep blue

autumn sky and the just-beginning-to-turn-yellow tamaracks surrounding the farm.

We heard Tom Lochner, executive director of the Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association, interviewed on Wisconsin Public Radio in early October. He said this year's harvest was

especially bountiful because the state had sunny days during June and July's pollination period, warm temperatures early on and timely rains.

Lochner said Wisconsin is a good state to grow cranberries in because of its abundance of fresh water, a heavy growth of evergreens that makes the soil acidic, and sandy soil that

allows for good drainage. The perennial wetland plant is long-lived and some bushes currently being harvested pre-date the Civil War. European settlers called them crane berries because

the blossom resembled the head of the sand hill crane.

Martin said that because harvest is so close to the end of the growing season, the berries may be damaged by frost. To protect them, sprinklers are placed in each bed and turned on if

the temperatures are predicted to reach freezing.

Water is also used to protect the bushes from the harsh Wisconsin winters. As winter approaches, the beds are flooded to encase the plants in ice.

Some years, a one-half to one-inch layer of sand is put on top of the ice, so when spring comes and the ice melts, the sand can settle down around the bushes. Lochner said this

encourages the roots to grow deeper and the bushes to grow upright. It also provides a cover to control weed seeds and insect eggs.

When I was young, cranberries usually came jellied in a can and were found on our table only during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. Today, the jellied berries have

largely been replaced by fresh cranberries cooked at home. But these make up only about five percent of the market. The rest are processed into juices, sweet dried fruit and other

products - products that are now finding their way to foreign markets as well as the traditional domestic ones..

Those "other products" each year lead to my spending hours at the Three Lakes Winery shop located where the old Chicago Northwestern train depot once stood. The winery made the state's

first commercial cranberry wine in 1972. While the owners now sell other types of wine as well, all-things cranberry are their focus - cranberry jams and jellies, cranberry syrup,

cranberry pancake mix, cranberry summer sausage, cranberry salsa, cranberry mustard, cranberry spread cheese, chocolate-covered cranberries, sweet dried cranberries, cranberry

trail mix and cranberry soaps, cranberry lotions, cranberry candles ... and so on.

In the Badger State, there are many places you can get a cranberry fix. At Culver's - a Wisconsin-based fast-food place - I lunched on a cranberry-bacon-bleu-cheese salad, and washed it all down with a cranberry shake!

But although I'm enamored with the variety of products made with cranberries, Art and our daughters prefer the little red fruit relatively unadulterated. For Thanksgiving, I make

simple cranberry sauce by boiling a mixture of water and sugar to which I add the whole fruit and wait until they "pop."

We don't eat cranberries just at Thanksgiving, either. Our freezer always has several packages, so we can have them at any time of the year. And our refrigerator is well-stocked with cranberry juice, too.

Unlike so many good-tasting things, cranberries are also good for us. While scientists are not certain why, drinking cranberry juice reduces the frequency of urinary tract

infections. Clues emerging from recent studies have shown that a compound in the berry seems to keep bacteria from attaching to tissues, something helpful in preventing stomach

ulcers, staph infections and gingivitis.

But it was Art who introduced me to perhaps the most unusual use of cranberries during our first Christmas together. He first popped popcorn and then let it sit out a few days so it

became rubbery. Then, he repeatedly poked a needle and thread through five bright-white kernels followed by a red cranberry. After several hours and several threads, he had three

striking home-made garlands for our tree.

And in one way or another, the little red berry has played an important part in our happy holidays ever since.