Grandview Cemetery: left, arch and bell from the Stockdale Methodist church;

right, Paddleford main stone above, Clementine's head and foot stones below.

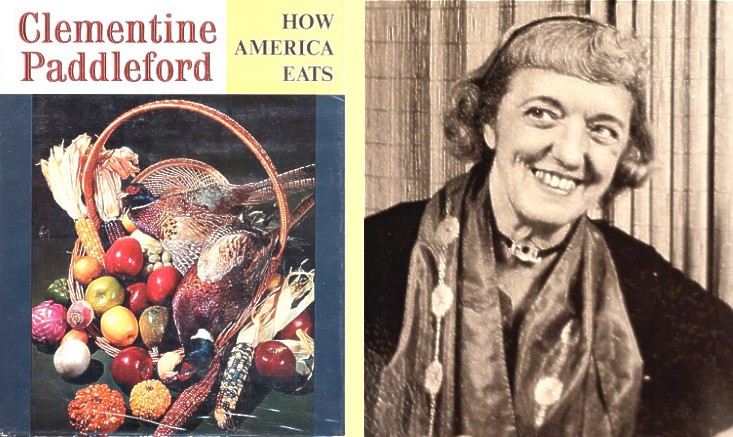

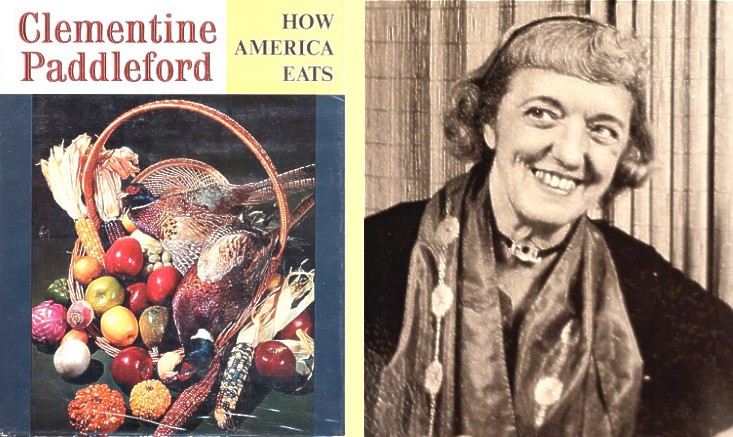

Left, one of Paddleford's cookbooks; right, Clementine Paddleford.

Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - July 16, 2010

From famous to forgotten and back again

At first glance, Grandview Cemetery isn't very different from so many other country cemeteries sprinkled across the Kansas landscape. Two gravel roads meet at its southwest corner, defining its western and southern edges. Its only distinguishing features are the abandoned one-room schoolhouse on its eastern margin and the small limestone archway with a bell near the center of the tree-lined hedge that forms its northern boundary.

There is a bit more to the cemetery than meets the eye. Both the arch and the bell were rescued from the nearby Methodist church that was inundated by the waters of Tuttle Creek reservoir when the dam on the Big Blue River to the east was completed. The graves in the eastern half are those of folks originally buried in cemeteries that were also covered by the rising waters.

But in most regards, it is remarkably unremarkable. There is far more land than is needed, so the tombstones are widely spaced. And the names on the markers - Gravenstein, Henton, White, Huff, Sweet, Crum - are certainly those of the Grant Township men who tilled the soil and their wives who kept their homes and bore their children.

Yet if a person is of a certain age, among the names of the hard-working members of the local farm families, one name seems a bit out of place. After all, isn't it natural to think that a person who was once a household name in millions of American homes must certainly have come from some appropriately fashionable place and not the flat farmlands of America's heartland?

And there certainly is no doubt about this person's celebrity status. When a book publisher makes the author's name larger than the book's title, you know he has calculated that the writer's fame is as likely to make a sale as the subject matter is. When a writer composes several columns each week for a newspaper as large as the New York Herald-Tribune and the column is syndicated across the United States with a total of 12 million readers, that columnist has definitely arrived. And when that status is maintained for more than three decades, the author is no flash-in-the-pan.

I am not of that age and, until just a few years ago, all I knew about her was that she had graduated from the journalism program at K-State and when she died, had left most of her papers to the university. But husband Art is just enough older to remember her columns in his hometown newspaper in Appleton, Wisconsin.

I think it is fair to say that Clementine Paddleford is a somewhat unusual name. But certainly it is no more unusual than the woman. She loved to write and, from an early age, her principal subject was food. By the time she was in her 30s, she was on her way to becoming the Julia Child for my mother's, and even my grandmother's, generation.

Yet she was not a cook. She didn't even care to cook. Her love was gathering and sharing the recipes of those who were experts in the culinary crafts, whether he was a chef employed by some famous restaurant or the homemaker next door toiling in her kitchen. Clementine traveled to France and Britain in her quests. So ardently did she work at her craft that she became a pilot so she could more quickly travel from her home in New York to places such as Texas, where there were chili recipes to be had. She went to sea aboard a submarine to document what the sailors ate. When Prime Minister Winston Churchill went to Fulton, Missouri to deliver his famous "iron curtain" across Europe speech, Paddleford reported on the food served.

At a time when most women's employment options were pretty much limited to librarian, nurse, school teacher or wife, and men thought $10,000 per year was a good wage, she was being paid $270,000 each year for her writing.

Who could have imagined such a career for the girl born to Jennie and Solon Paddleford on a farm in Grant Township of Riley County, Kansas? I'm sure her parents only hoped she would grow up to be healthy, for so many babies died then.

Jennie never lived to see her daughter hit her stride as an author and so she never knew how often Clementine wrote about her and her cooking.

Paddleford was married briefly. Her life was probably too full to have room for a husband and a family, although she did everything up to legally adopting a friend's daughter.

Clementine died in 1967. Until two years ago, except to a few like Art, she was all but forgotten. The food landscape has changed dramatically since she was in her prime and most people today probably think of James Beard and Julia Child as the pioneers of food journalism.

But Kelly Alexander, an editor at Saveur magazine, and Cynthia Harris, an archivist at K-State, restored a bit of the fame Paddleford once enjoyed when Gotham Books published their work "Hometown Appetites." Its flyleaf describes Paddleford as "the most important food writer you've never heard of."

I long ago learned that each person has at least one story worth telling. Perhaps that is true for each place as well. I now know that the ordinary-appearing little cemetery on Fairview Church Road certainly has one.

Grandview Cemetery: left, arch and bell from the Stockdale Methodist church;

right, Paddleford main stone above, Clementine's head and foot stones below.

Left, one of Paddleford's cookbooks; right, Clementine Paddleford.