Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - Feb. 19, 2010

Memories still vivid after 65 years

Most youngsters look forward to their 21st birthday with great anticipation. Julian Siebert was just hoping to live to see his.

Growing up on a farm near Westmoreland, Kan., he left for Fort Leavenworth on May 4, 1944 with good friend Clyde Aubert. They were inducted the next day, trained in Texas and traveled overseas, first to Britain and then France. They were assigned to the 328th Infantry as replacements, taking the positions of soldiers injured or killed.

On Nov. 20, just eight days before Julian's birthday, they went into battle near Dieuze. He clearly remembers it. Clyde was killed.

"This was my first realization of the price we pay in war," he said.

I had seen Julian's photo in the paper after he and other area veterans traveled to Washington, D.C. on an Honor Flight trip to see the national World War II Memorial. Husband Art and I met him and wife Barbara for lunch shortly before Christmas.

We asked him about some of his World War II experiences.

The night before his birthday, they were dug in at the edge of a small town. The next day several men went to mass in the church behind them. That afternoon, they came under artillery fire that seemed to follow them when they moved. Later, a sniper fired from the church steeple and they knew he must have been spotting for the guns.

"Between the artillery and the sniper, it got so hot that I found an old foxhole that was full of water," he said. "I broke the ice on top with the butt of my rifle and jumped up to my shoulders in water. That night the sniper tried to escape, but he didn't make it."

About mid-December - after nearly a month of continuous fighting - his unit was relieved and went to Metz, France for a rest and to spend Christmas. But the offensive Americans call the Battle of the Bulge began the next day, sending him back to the front.

"Our assignment was to find the enemy and engage him," he said. " . . . At this time, the Germans had American uniforms and some spoke good English so it was difficult to know if you encountered Germans or Americans . . . There was lots of snow on the ground and the Germans would sometimes wear white over their uniforms so it was hard to see them . . . "

Julian's farm experience came in handy.

"Sometimes we would see a milk cow and it was my job to milk her as I was the only one who knew how and we would heat it and put D-bars in it to make some hot milk chocolate."

Early on Christmas morning, when kids back home were waking up to see what Santa had brought, his company attacked a small town and met some strong resistance. His squad was cut off from the rest of the group.

"Shells went off in front of us. It took the pack from my back and scratched my back. The man next to me was killed. We moved into a building and tried to hold off there."

A hand grenade was thrown into the room, but he and his buddies couldn't find it in the dark, so they hit the corners of the room. It went off, but no one was injured.

"Later they pointed the tank's 88 gun at us so we came out as we knew this was the end, and we were taken prisoners."

They were taken behind German lines and were lined up behind a hill.

"We knew they were about to shoot us. The fellow next to me said, 'It looks like this is it.' I answered, 'It sure looks like it.' It was real quiet from then on. I guess there was a lot of praying going on about then."

A vehicle similar to a Jeep came around the hill and a German officer got out and talked to their captors. The prisoners were then lined up and marched out.

They walked for days, collecting more prisoners as they went. Finally they arrived at a railroad yard with a lone boxcar and were loaded into it.

"There was only room enough to stand, but we were left for several days . . . ," he said.

He learned that it was possible to sleep standing up. Things got worse when some became ill.

They were transported to Stalag 12A, a prisoner-of-war camp near Limburg, Germany. Guards questioned them, gave them identification tags and took their photos.

The camp had no facilities for bathing or washing and food was in short supply, consisting mostly of soup. But even under those grim circumstances, prisoners tried to find humor.

"One guy said at first if you see a worm in your soup, you will probably throw it out. Then if you see a worm in your soup, you will pick it out and eat the soup. After that, if you find a worm in your soup and he tries to crawl out, you will knock him back in."

Julian was among a group of 30 who worked in a forest cutting pine trees.

"One night, one of the guards gave us an ax and told us that if things got too bad we should break ourselves out of the barracks for our own protection. The next day we were told that the Russians were getting close and we were going to the American lines. We walked all day and at one time the Russians were firing in one side of a small town as we went out the other side. Finally the guards gave us their guns and said, 'We are your prisoners now.' We were almost to the American lines. This was May 2, 1945. The war was almost over."

When reflecting on his experiences, Barbara said Julian has often mentioned what a beautiful sight the American flag was when he got to the American lines.

Although the Battle of the Bulge is now more than 65 years ago, many who fought in it remember details vividly.

"When they say, 'freedom isn't free,'" remarked Julian, "that sure is the truth."

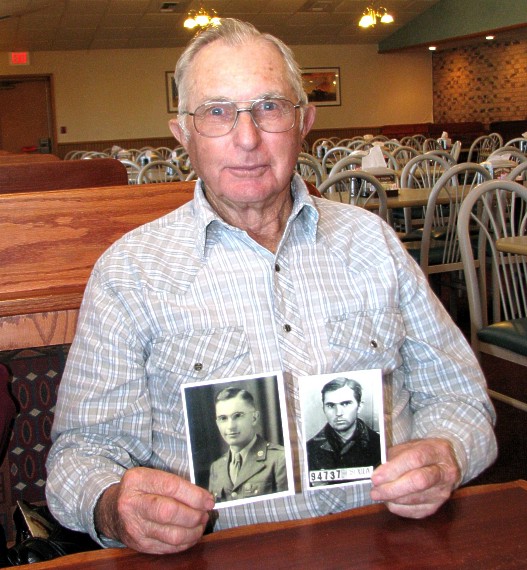

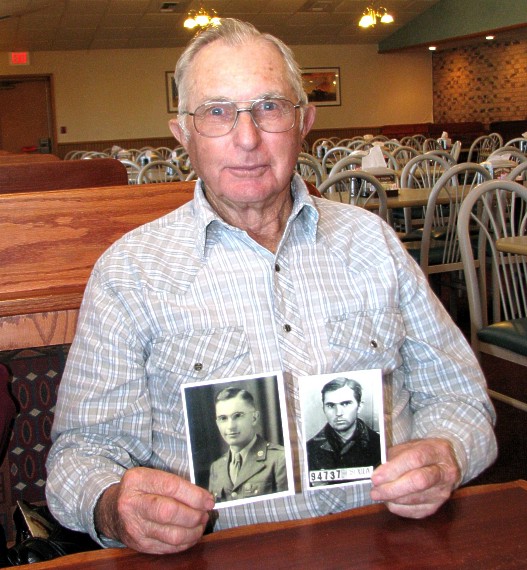

Julian Siebert holds the two photos taken of him during his World War II service. In his right hand is the one his mother insisted be taken before he went overseas. The photo in his left hand was taken as he entered POW camp Stalag 12A.