�The Miracle of Dunkirk�: A Christmas Tale

It is the tale of two cities of the same name; at its heart lies mankind�s hope for peace

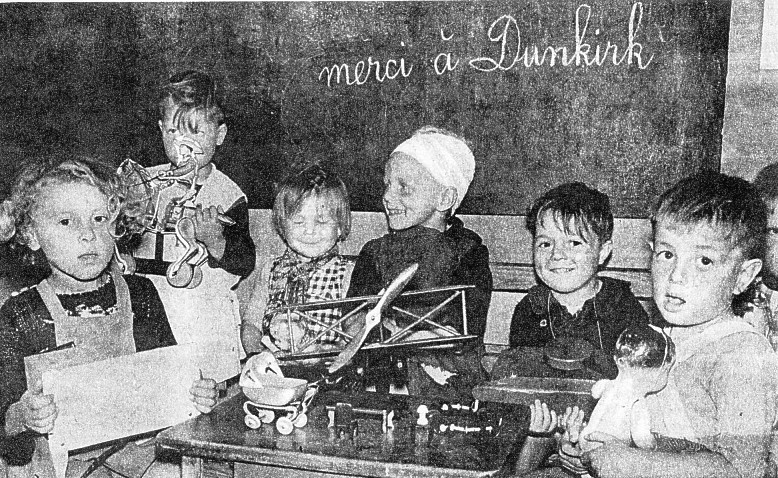

Youngsters of Dunkirque, France thank friends of Dunkirk, N.Y. for gifts of toys.

by Meyer Berger

Dunkirk, N.Y. � This is a tale of two cities which, by a kind of latter-day miracle, has become the tale of many

cities. Hundreds of thousands of earnest people who have heard or read of it, piecemeal, seem to think that

somewhere at the heart of it lies mankind's hope for peace. They say, �Perhaps this is the pattern. Perhaps peace

cannot come from the top � from fussy diplomats and from the cold. formal hand of Governments � but only from the

bottom, from the little people whose hearts and minds cry out for it.�

The miracle � now variously called �The Little Marshall Plan� and �The One World Plan� � originated in this

smoke-blackened city on stormy Lake Erie. It has spread with astonishing swiftness to cities all over the United

States. Dunkirk, N. Y., took Dunkerque, France, to be a kind of sister city. Her little people established warm

kinship with the little people of the North Sea Dunkerque. Americans in other states looked upon this sisterhood

and found it somehow heart-filling and genuine. They moved toward similar adoption.

Most remarkable of little Dunkirk�s miraculous achievements was the fact that she did not stop with the adoption

of the French town. Her miracle was three phased. Though she is comparatively poor in worldly goods, she found it

possible to take part of war-racked Poland to sisterhood, and then Anzio, in Italy too.

The first phase started a little over a year ago, but to understand it, you must know something of the histories

of the cities that figure in it.

Dunkirk, New York, is a shop and factory town. Of its 18,000 to 20,000 towns-folk, perhaps 85 per cent are men who

toil for their bread � fishermen, steelworkers, silk-mill hands and the like. Their city, only a little over five

miles square, lies black and melancholy under biting gales off the lake.

Though it is softly green in gentler seasons, in winter it looks tired and cold, and very old. Its children and

their parents are all but blown down Central Avenue, its short main street; they are in heavy woolens, in snow

suits, ear-muffed, red-cheeked, with heads kerchiefed against the tooth-edged blast. Their city was founded at

the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Dunkerque, France, was founded ten centuries before the shop town on Lake Erie. As Dunkirk looks out on the lake,

Dunkerque looks out upon the cold North Sea, beyond Calais. Before the war, it had some 60,000 souls. They fished,

as Dunkirkers do. Instead of steel and silk, they made fishing nets, straw hats, starch, soap, rope and sailcloth.

They worshiped in the Chapel of Notre Dame des Dunes, built In 1405, and in the Church of St. Eloi, put up in 1560.

Their town was 700 years old before Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the New World. Close to two more centuries

passed before the Sieur de La Salle first looked upon Lake Erie. It was in its 1,000th year when Elisha Jenkins,

who was Secretary of State for New York and a man widely traveled, fancied that the little harbor on the lake

resembled Dunkerque Harbor on the North Sea. Through his influence, he caused its name to be changed from Chadwick's

Bay to Dunkirk. This was the sole kinship between the two cities, except that the people in both are simple folk,

and, for the most part, poor.

The second World War came and Dunkerque on the North Sea was reduced to rubble and utter misery. Britain's army was

trapped on its beaches. The proud towers of its churches were reduced to crumbled brick and dust. Its quays were

shattered. Its city hall was bombed into oblivion. Its crowded dwellings went to powder and wreckage. Its humble

peoples were scattered. Its foremost citizens died before German firing squads. When the war ended, of its 60,000

souls, only some 640 came back. These starved and shivered in thin rags in the North Sea gale.

One day in September in 1946, Lafe Todd, who had been an Army public relations captain, came back to Dunkirk where

he had spent his boyhood. He was interested in the American Aid for France movement. He talked with Wallace Brennan,

who writes the editorials for The Dunkirk Evening Observer, and with Roman Wiate, the city's industrial commissioner,

about raising a few hundred dollars for Dunkerque on the North Sea. He cited the name kinship. They liked the idea

and so did Mayor Walter Murray when they discussed it with him.

Wally Brennan � everyone in town calls him Wally as he comes down Central Avenue from The Observer office in Second

Street for his late afternoon refreshment � sat down and wrote a piece he hoped would appeal to the mill workers and

the steel workers in the city. He wrote:

�Suppose, Dunkirkers, that the tide of war had passed over your beautiful city. Suppose, let us say, that five years

ago, the beaten troops of one nation began marching into your city, pursued by an arrogant and insatiable conqueror.

When the beaten army got away, the conqueror stayed on for five long years and for five long years your city was

subjected to daily bombing. You huddled in your cellars or slept in the open or fled to the hills.

�The conqueror, of course, took everything. He seized what was left of your home. You were underfed and poorly clad.

Your schools were destroyed. Your public buildings were a shambles. You could not seek the comfort of your churches,

because the churches were piles of rubble. And then, one day, after the evil things of the harsh years, there

arrived a little help from another and distant country. There were still hearts in the world capable of responding

to your dire and pitiful need. The understanding gesture of a distant city could let in a little ray of hope. We

can do, maybe, just a little for the physical well-being of Dunkerque in France. Inevitably, we will do much more,

in a spiritual sense, for ourselves.�

Ask the men and women in Dunkirk today how they came to �rare back and pass their miracle,� and they seem puzzled at

the question. They do not trace it to Wally Brennan�s editorial. They never connect it with Lafe Todd�s suggestion.

They did not do it with any thought of political advantage. It never occurred to them that they might be showing

the rest of America a possible new avenue to peace for mankind. �Motive?� they say now. �There was motive. Those

poor people had no homes and no food and no clothing, and we had some extra and I guess that was the way of it.�

That�s the way you get it from Nels Currier, who heads Local 2693 of the United Steelworkers of America down at the

Allegheny Ludlum Steel Corporation � big 242-pound, gruff Nels, the hammersmith. That's the way you get it from

leather-jerkined, stogie-smoking George Privateer who works around the Dunkirk canneries; from the girls in the Van

Raalte Mills, from the help in Bill Cease's Industrial Commissary; from the lumber-jacketed huskies at the American

Fork and Hoe Company; from the girls in Julius Weinberg�s Safe Store; from the weathered crews on the whitefish and

cisco fleets, and from red-faced loungers in Jack Haire's bar in the shabby Francis Hotel.

Anyway, the little City of Dunkirk did pass its miracle. It went far beyond Lafe Todd�s and Wally Brennan�s hope of

getting a few hundred dollars for Dunkerque; it piled up, before Thanksgiving Day, close to $100,000 worth of gifts

for the broken sister city on the North Sea. The steelworkers brought in hundreds of garden tools � rakes and hoes

and spades and picks and hammers. The Elks Club donated one bull and Farmer Lynn Hawkins out on Second Forestville

Road, donated another. The Dunkirk Red Cross rolled miles of bandages and made other surgical dressings.

Ten young cows that would bear in the spring were paid for by the Loyal Order of Moose, the Loyal Order of Billy

Goats, Joe Caruso's Columbus Club, by the Eagles, the Polish Falcons and Kosciusko Club, by the Lake Side Club

members and by the Town Mason. The Hebrew Ladies and the ACE, another women's group, bought piles of new, warm wool

blankets, the city�s twenty-one churches, representing seventeen denominations, bought $1,500 worth of powdered milk

and powdered chocolate milk. Tanners brought in ten pigs and twelve goats.

The town�s stores gave of their wares. Some of it was slow-moving stock, but it was new. Dunkirk housewives gave

bedding and surplus clothing and shoes for men, women and children. The kids in the schools gave pencils and copy

books. The teenagers in the High School Y.M.C.A. saved up $150 and bought a microscope. Doctors contributed medical

supplies and precious machines and instruments. The canneries sent in truckloads of canned fruit, canned meats,

canned jellies. The city sent out its trucks so that volunteer workers could fetch all the stuff to the fire houses.

And the miracle grew.

It grew, and it spread. Big-town newspapers caught up the story and sent it over the land, and news agencies sent

it across the sea. Readers, hundreds and thousands of miles from Dunkirk on the Lake, sent money or special gifts.

Important people talked about it. When Thanksgiving Day came in 1946, Dunkirk was world news. Ambassador Henri

Bonnet came with Madam Bonnet and with Canadian dignitaries to see Dunkirk's gifts paraded down Central Avenue on

a mile of motor trucks. Charles Boyer and Simone Simon stood in the reviewing stand with them, and Dunkirk's

populace thrilled to their visit.

The school children of Dunkirk staged a pageant written by Miss Katherine Drago of their town. It was a touching

performance. When Cliff Drum, the steelworker, and Nellie Greder, who came here as a war bride from France after

World War I, posed under soft lights in a representation of Millet's "The Angelus" and the bell tolled, Mrs.

Bonnet was misty-eyed and women of Dunkirk were wet-cheeked. This was all part of the miracle, and to many, proof

that the way to peace is through the hearts of simple people. Russell Davenport, who came from New York City with

the other visitors, was moved.

He said, "Let this light shine forth that we may demonstrate to the nations of the earth our conviction that the

security, the freedom of man, is indivisible. ... We say to the United States of America,'Here on the shore of

Lake Erie, one of your cities has seen the light.'�

And, curiously, the light seemed to diffuse over the land as it does in picture-book miracles. It penetrated to

far places. Mayor Murray and Miss Drago and Wally Brennan and Rome Wiate found their mail suddenly extraordinarily

heavy. It came from hamlets and villages, and from towns and cities, from Concord. Mass.; from Port Orchard in

Washington; Granville Ohio; Hanover, N.H., Orem in Utah; Fort Smith in Arkansas; Catskill, N.Y., Orangeburg in

South Carolina; Kansas City, Mo.; White Plains, N. Y.; Franklin, Pa.; Williams Bay, Wis.; Alvarado, Tex. � from

poor towns, and from communities middling-rich, from some that had the greatest wealth concentration in the

richest land on earth.

And all the cities, villages and towns, including Locust Valley and White Plains, asked little Dunkirk the same

question. They asked, in effect, how did you do this thing? How did it start? And they asked, will you tell us how

we might go about doing as you did?

This was the magic of Dunkirk�s miracle. In the little city of its origin, it brought together the steelworkers like

Nels Currier and Cliff Drum, to sit at meeting with the few well-to-do citizens of Dunkirk. It brought the Catholic

and the Protestant to sit with the Jew and the Christian Scientist. It brought the union man to sit in harmony with

his employer. As it moved across the country, it brought wee Dunkirk, with its total assessed valuation of

$15,838,000 to sit, so to speak, with Locust Valley, in Long Island, home of fabulously rich folk, including many

who could have bought all of Dunkirk, if they were so minded.

Today, Dunkirk cannot say what more it can or will do for European cities that are down on their hands and knees in

utter despair. Wally Brennan, and the Mayor, and Rome Wiate have organized The Dunkirk Society which meets in the

town courthouse about once each fortnight. They may never duplicate their gifts to Dunkerque and Poland and Anzio.

The town's little people, the town�s shopkeepers and even the well-to-do have pretty well scraped the bottom of the

barrel for things to send abroad. They do feel, though, that the idea they fostered will not die.

Beyond that, Dunkirkers keep busy answering the heart-filling letters that come from overseas, and that are a

spiritual transfusion between the benefactors and the crushed who benefitted. Bill Cease, who is inclined to talk

in parables, says, �A man walks a bitter cold road toward world peace and is in danger of freezing to death. Along

the way, he sees a fellow-human dying in the same road. He stops and kneels by his side to save him. Through his

efforts, he not only saves the dying man, but restores his own circulation. Both are warmed and can walk the road

toward peace together.�

Mind you, Bill Cease can be lusty � even profane � when he tries to put an idea across, but this parable is almost

Scriptural. It comes as close as anything to telling what happened in ice-bound Dunkirk on Lake Erie when it went

to the aid of Dunkerque on the North Sea.

Wally Brennan has his own explanation of the miracle. He says:

�Deep down, maybe everybody in the United States, probably most human beings on earth, want to do something about peace. The people feel that they, or their sons, are called on to fight the wars, and when the sons come home � those who do come home � and put the peace problems in the hands of their diplomats, the diplomats always fail them. Deep down, I think, what happened in Dunkirk and what is happening now in other communities, is that the people are trying to express their yearning for peace. They want desperately to do something about the peace. They need only some kind of leadership.�

And Dunkirk�s small-fry have come to know, somehow, that other children starve and shiver in war-devastated lands,

far from Lake Erie. Susan Muscato, who is only 9 years old, dumped $1.67 � mostly pennies � out of her purse at a

Dunkirk Society meeting in the court house the other night. She told the chairman, the flooring contractor John

McCauliff, "I want to give this money to the little boys and girls who are hungry in Anzio.� And John McCauliff

swallowed and asked, �Where did you get these pennies, Susan?� Susan bit into her lower lip. She said, bravely,

�I was saving to buy a horse � and I loved him so.� John McCauliff couldn�t go on with the meeting because his eyes

melted and. his throat held back the words. Wally Brennan took over.

Rachel Barris, recording secretary for the Dunkirk Society, was at her desk, another day, when Anthony Conti, who

is barely 5 years old, handed up a coldcream jar filled with coppers he had saved for candy money. Anthony�s father

is head of the business department in Dunkirk High. �Take all the money,� little Anthony said, �I�m not going to

cry.�

Dunkirque's citizens, children and adults, write regularly to Le Maire Murray, to Miss Drago and to Monsieur

Brennan about the disposition of the gifts, that came from Dunkirk on Lake Erie.

�For the girls, we set aside pieces of material, sewing kits and a pile of old felt hats to be fashioned into warm

slippers. For the boys, we reserved the tools � hammers, saws, hinges, trowels and the like � to be used in the

workshops. The baby carriages, especially the wicker ones, have had more success as cots than as perambulators.

Most of the infants now enjoying them had slept with their parents, or on broken chairs set together.�

�The microscope, jewel of the collection from Dunkirk, has been given to a young doctor. ... The work of unpacking

and sorting in the Dunkerque Museum has been made painful by the north wind, which has reappeared with the bad

weather to whistle through the windows, all without glass, to storm its way unhindered through the great rooms,

about thirty feet high.�

Louis Boyaval, who is a gendarme in Dunkerque, has written: �When I went home this evening, I found the children

and their mother joyous over the contents of their package from Dunkirk, and I myself was overcome by gratitude

toward our American benefactors. �He wrote of his wife Mariette, of Hos� and Reginald, his sons, and his daughter,

who is 3 years old. �Do me the honor,� he wrote in closing, �of addressing some words to a French policeman and

his family.�

After a Dunklrk Society meeting in the City Hall the other night, some of the women fell to talking again of how

the idea seemed to have caught on all over the country, and how wonderful it was to have cities writing in for

information on how to organize to help some stricken community across the water. One said, �I still can�t

understand, though we've seen it with our own eyes, how it all could have started in a place as small as our city.�

And Katherine Drago smiled. She said gently, �There have been miracles in other little towns. There was one in a

little town called Bethlehem.�

December 21, 1947

New York Times Magazine