Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - August 16, 2019

"Nuts!"

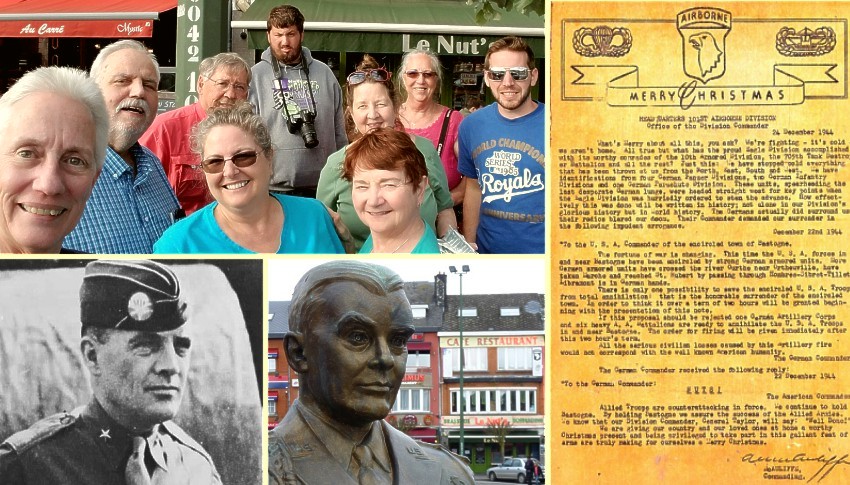

I am often intrigued how some stories endure, while others enjoy a period of prominence and then disappear. This was underscored by a

message I received from friend Jay after we two and several others shared time together in Europe this past June. When family or

friends gather, someone will often prompt another with, “Tell the one about .....” Jay’s message was in that vein.

I am amazed at how few people over here [in the States] know anything about the “nuts” story at Bastogne. Might be an educational

story for your column.

Jay was referring to a headline-making story that has now pretty much faded away.

A starting point for the tale might be the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944. The United States had experienced one piece of

bad news after another in regard to the war until the previous year when things began to turn in the Allies' favor. Germany had proven

to be a resilient foe. So Allied commander and future president Dwight Eisenhower had prepared two statements before the landing - one

to be read if all went well, and another to be published if the effort failed.

It succeeded well beyond expectations. Instead of a Christmas battle to retake Paris as had been thought, the Allies had crossed all

of France and were regrouping at the border of Germany as Christmas neared.

But the sprint across France had left the troops tired and supply lines stretched thin. Then winter arrived. With troops spread from

the Mediterranean Sea in the south to the Netherlands in the north, there were not enough rested men to cover the entire front. The

area west of Luxembourg was only lightly defended, having been designated an area of rest and relaxation. The heavily-forested rolling

lands to the east would be a nightmare to move a substantial force through and it was assumed Germany would not be so foolish as to

try.

But Germany was desperate. With the bad winter weather hiding its efforts, a huge force was accumulated on the eastern edge of the

Ardennes forest. German leader Adolph Hitler knew he had insufficient resources to defeat the Allies. But if he could break through

to the port of Antwerp and divide the American forces from the British ones, festering political divisions in the Allied ranks might

explode and the Allies would sue for peace.

The plan was doomed from the start. The German chancellor did not know that whatever divisions existed between the Allies were small

and they had also agreed to not stop at anything short of total victory.

The Allies were caught completely by surprise on Dec. 16 when German forces began advancing from the woods. Within a few days,

they had secured a huge westward bulge in the Allied lines. But while German forces were in control of almost all areas east of the

front, the Belgian town of Bastogne was a small pocket of Allied resistance. The village of 4,000 inhabitants had also become the

home to the 101st Airborne. Its commander Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor was away from the unit and so command had passed on to Brig.

Gen. Anthony McAuliffe.

Bad weather meant there would be no help from the Air Force for the “Battling Bastards of Bastogne,” as they came to be called.

Gen. Heinrich von Lüttwitz, the German commander, sent a message to McAuliffe on Dec. 22 that read, in part:

The U.S.A. forces in and near Bastogne have been encircled by strong German armored units. ... There is only one possibility to save

the encircled U.S.A. troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable surrender ... a term of two hours will be granted

beginning with the presentation of this note. If ... rejected, one German Artillery Corps and six heavy A. A. Battalions are ready to

annihilate the U.S.A. troops.

From a military perspective, the loss of Bastogne was somewhat important. Good roads were in short supply as was fuel for the German

advance. The junction of several roads at Bastogne was important. Its control by the Americans meant alternate heavy fuel-consuming

routes over rugged ground would have to be found for German vehicles to keep the advance on schedule.

McAuliffe was unusual in that his soldiers said he never swore. His answer to the German ultimatum was just one word: “Nuts!”

Two days later, Christmas Eve, he issued a note to the men in his command which began with a large “Merry Christmas.” He then

continued, “What’s merry about all this you ask? We’re fighting - it’s cold - we aren’t home. All true ...”

He included the full content of the messages exchanged between the commanders and then concluded with:

By holding Bastogne, we assure the success of the Allied Armies. We know that our Division Commander, General Taylor, will say,

“Well Done!”

We are giving our country and our loved ones at home a worthy Christmas present and being privileged to take part in the gallant

feat of arms are truly making ourselves a Merry Christmas.

The Germans hadn’t been sure what to make of the one-word response from McAuliffe, and so Col. Joseph Harper, who had

delivered the note, was asked what it meant. His response was, “In plain English? Go to hell!”

The Americans were able to hold until the day after Christmas when a break in the weather allowed C-47 cargo planes to drop

much-needed supplies and Gen. George Patton’s Third Army arrived from the south after liberating Metz. The Allied forces began

systematically pushing German forces eastward. Americans at home saw what happened at Bastogne as both a turning point and as a sign

that ultimate victory was not far off.

McAuliffe later became a four-star general and commander of all forces in post-war Europe. After retiring, he had a successful

career at American Cyanamid Corporation.

But while the story and his part in it is now largely forgotten, the meaning endures. As Jay said, “The message? No matter how dire

the situation, never, never give up.”