Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - June 14, 2019

Buxton

Quite out of the blue as we were finishing supper at a restaurant a few weeks ago, my nephew’s son Dominic asked if anyone in our

family had ever been involved in a disaster. It made us all laugh. Still, it is natural to wonder if a person’s family was ever

connected with something famous. Being the family historian, I began combing through my memories, looking for what may be the most

unusual aspect of our gang.

While we are pretty ordinary folk, we do have a connection to something that is the opposite of a disaster, something very good and

unusual to the point of possibly being unique. And it happened in Iowa, a place known more for caucusing and corn than coal - the

focus of this story.

When the Civil War ended, railroading began to boom. The Midwest, which had once been covered by a shallow sea, had veins of coal

here and there - a resource much needed by the steam-powered iron horses of the time. In 1881, the Chicago & NorthWestern Railroad

bought the Consolidation Coal Company mines at Muchakinock in southeast Iowa. Unions were gaining a foothold and strikes were a

problem. CCC tried a unique solution. It dispatched recruiters to states such as Virginia to convince African-American workers to

become miners. While the war had been over for 16 years, opportunities for blacks in the Old South were little better than before.

Racial segregation, discrimination and violence by the Ku Klux Klan were common throughout the U.S.

Muchakinock was a company town with a store, barber shops, grade schools, churches, a band and a baseball team. It even had a

newspaper called the Negro Solicitor. By 1895, about 3,800 people called it home. But few would have thought it would foster the

creation of what some consider to be a utopian community for black miners and their families.

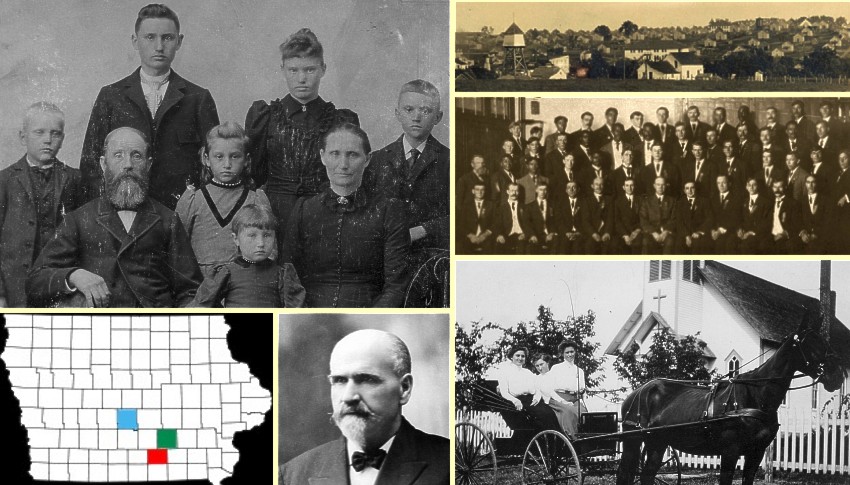

While most of the community members were black, there were white immigrants from the British Isles, Slovakia, Italy and Sweden. My

great-grandparents Johan Olaf and Maria Carlberg were among this latter group, having moved from southern Sweden in 1882. In 1890,

Hulda, my grandmother and last child, joined siblings Elin, Sven Johan, Joseph, Hannah and Gustav.

But in 1896, tragedy struck. Johan died when a slab fell from the mine roof. Maria supported the family by operating a boarding house.

By 1900, with the veins running out, the company purchased an additional 10,200 acres a few miles to the west in Monroe and Mahaska

counties and began construction of Buxton, a planned community named after J.E. Buxton and his son Ben, the company managers. Within

a few years, there were about 5,000 residents, including the Carlbergs. The town included three elementary schools, a high school,

several parks, 11 churches and a YMCA. Residents formed a brass band and sports teams. African-Americans were paid the same wages

and given the same accommodations as their white counterparts. The town had black teachers, lawyers, a dentist, a doctor and business

leaders.

The Carberg family grew smaller as the children grew to adulthood and left. Elin, the oldest, died in 1911, and was buried by her

father. Maria and the younger ones moved to Colorado where several of her brothers were living.

By the mid-1920s, the coal was depleted in Buxton and the village disappeared almost as quickly as it had appeared. Some buildings

were moved or materials scavenged. Others were left to decay. The Lutheran Church was a victim of fire. So when husband Art, my

parents and I visited in 1994, there wasn’t much to see. We later watched an Iowa Public Television documentary about the town and

were amused to see among the images a photo of Hulda and her sister Elin sitting in a buggy. The story then faded from our attention.

Earlier this year, quite by chance, I came across the books, “Creating the Black Utopia of Buxton, Iowa” and “Lost Buxton” by Rachelle

Chase.

This led to finding the online video, “Searching for Buxton.” David Gradwohl, emeritus professor of anthropology at Iowa State University, was among those interviewed in the video. He did

extensive research on Buxton and, in 1984, he and colleague Nancy Osborn did a program, “Blacks and Whites in Buxton: A Site Explored,

A Town Remembered” as well as a book which is still in print.

The Buxton story was brought into the limelight in March, when U.S. Sen. Cory Booker was in Iowa campaigning for president. He

described his great-great-grandmother Adeline McDonald’s experience as a widow struggling to raise 10 kids in Alabama. Wanting to

escape the poverty and racial oppression of the South, she moved to Buxton with nine of her children, and found the stories she had

heard of racial equality were true.

In an interview reported in the Des Moines Register, he said the Iowa town helped his family lift themselves out of poverty. He said

Buxton was a place where even people who were struggling welcomed strangers.

He and others interviewed about Buxton over the years ponder how such a racially-integrated, progressive community could exist so

long ago.

“People weren’t strangers, they were neighbors,” Gradwohl said in the 2011 video. “... Why can’t it exist today?”

But with the village's demise, like the others, Booker’s family had to move. His grandmother was raised in Des Moines and he still has

relatives in the area.

But those who went through the move reported it was a shock to again experience the attitudes and treatment they had been so familiar

with before they arrived in Buxton. It was not that things were better in the little Iowa community because the country was changing.

In fact, the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan was still ahead and much of its support was centered in the Midwest. Buxton was different

because the Buxtons designed it that way and wouldn’t tolerate what was going on so many other places.

So, Dominic, our family has not been associated with any disasters, but our connection with a bit of utopia is pretty good.