Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - April 30, 2018

Hitting the hay any time of day?

One night - or I should say morning - last week, I was awake from 1:30-4:30 a.m. Just as I started to drift back to sleep,

husband Art awoke. He later told me he was awake from 4:30-7:30 a.m. We both dragged ourselves out of bed and stumbled

through the early part of the day. He eventually succumbed to the need for more shut-eye at around 2 p.m. I followed about

3 hours later. That evening, we both commented how refreshed we felt after a second dose of slumber.

I used to catch a few extra winks on weekends, but haven’t done it for years. I had forgotten how luxurious a nice nap could be.

It also made me think about the importance of sleep to our health.

There is certainly no shortage of folks with advice on the subject of sleep. In a USA Today article from January 18 about

avoiding the effects of jet lag when going to Europe, the author wrote: "Stay awake. It's the only way to set to the local

time. It may be 8 a.m. when arriving in London, but the body is saying 'No, it's only 2 a.m., I should be asleep.' Start

the European vacation right away."

Not so sure. One year we drove to our room in Rothenburg, Germany and immediately took a three-hour nap. We then went out,

feeling refreshed, and slept fine that night. On another occasion, we had barely left London's Heathrow airport when Art

mentioned he was tired. We pulled into a "lay-by," as the Brits call a rest area, slept an hour, and then went on our way

quite refreshed. Somehow, "pushing through" tiredness on a busy highway just doesn't sound smart.

In a March 18 “Parade” magazine article - “Sweet Dreams Are Made of This” - I learned March is National Sleep Awareness

Month. I was hoping for some tips on getting better sleep. Instead, it advertised products that supposedly would bring the

Sandman. They included a sleep spray made from frankincense, hops and lavender essential oils to squirt on my pillow ($25); a

remote-controlled noise and light therapy device ($100); a weighted blanket ($199); and fancy pajamas ($128.) Those prices

would be inclined to give me nightmares rather than help me dream!

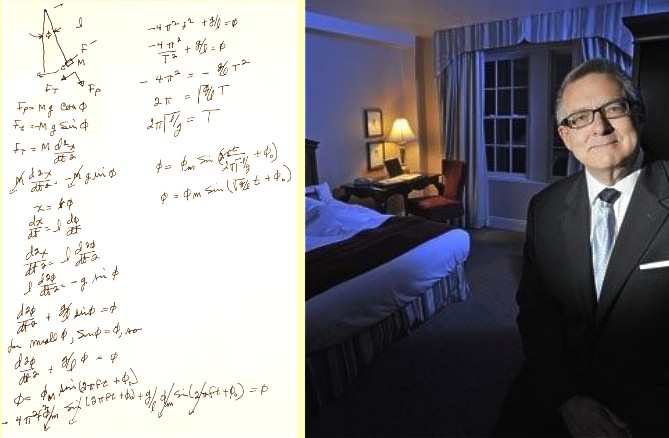

Art doesn’t seem to worry about interrupted sleep like I do. Whereas I tend to stew about things I have to do the next day or

over the next few weeks, he quite likes the quiet in the middle of the night - a time he says he can work out problems he’s

been wrestling with. Sometimes his night-time musings produce complicated mathematical formulas that he revisits upon

awakening. About the only thing I produce during my middle-of-the-night wake time is a

hard-to-read-because-I-wrote-it-in-the-dark to-do list.

And I know it’s not just me. I have friends and colleagues who frequently tell me how exhausted they are. Our British friends

commonly recognize two levels of being tired. Being “knackered” is the run-of-the-mill condition, but when you are “shattered”

- well, no more need be said.

I Googled “sleep” and found all kinds of articles, most discussing the lost productivity due to people working sleepy and the

dangers to people’s health when they are short on rest - all things I’ve heard before. They prompt me to get more sleep. But,

like eating better, it is so easy to slip back into old habits.

But I did come across one article that was quite different and addressed that business about lying awake in the middle of the

night. The 2012 broadcast on the BBC’s World Service report was titled “The myth of the eight-hour sleep.” Although the story

was British, it featured Virginia Tech history professor A. Roger Ekirch, the recipient of the university's 2009 Alumni Award

for Excellence in Research. He's discovered evidence from science and history suggesting that a big chunk of uninterrupted

sleep was not natural at all. Ekirch found more than 500 references - from diaries, court records, medical books and

literature - that showed humans used to sleep in two time segments.

In his 2005 book, “At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past,” Ekirch’s subjects described a “first sleep,” which began two hours

after dusk, followed by a waking period of one or two hours, and then a “second sleep.” He found in the references that people

were active during the intermediate period, often getting up to go to the bathroom, smoking or even visiting neighbors. Many

read, wrote and prayed. It was suggested it was also an ideal period for husbands and wives to engage in doing something that

they are often too tired to attend to upon first going to bed or too distracted to give their full attention when

awakening before a busy day.

Among Ekirch’s findings were prayer manuals from the late 15th century that had special prayers for the hours between sleeps.

But references to first and second sleep began to disappear during the 1700s, when industrialization began to take hold in

northern Europe. It continued to fade over the next 200 years in the rest of Western society. Ekirch said by the 1920s, the

idea of a first and second sleep had receded from our consciousness. In addition to industrialization, improved street and

home lighting and the opening of coffee houses and other businesses that stayed open all night contributed to this change.

So maybe lying awake isn’t as bad for me as I thought. Art has often encouraged me when I awake to get up for a bit or perhaps

walk around the house before returning to bed. We do know that getting enough ZZZs is important for mental and physical

health, but maybe that one long sleep is more of a nod to our modern world than to our internal need.