Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - September 22, 2017

Rocks, registers and ruts

To say husband Art and I traveled a lot this past summer would be an understatement. After putting 3,500 miles on our

rental car in Great Britain and Europe, we returned to the States and drove an additional 3,000 miles from Kansas to the

Wyoming wedding of daughter Katie and son-in-law Matt, back east through the Badlands of South Dakota, into Minnesota and

finally to our cottage in northern Wisconsin.

We both like to journey by the “scenic route” - which usually means a longer drive, but a much-more interesting one. Along

the way, we saw dozens of prong-horned antelope, a herd of bison, several bighorn sheep and a moose; the Wind River

Reservation; the natural geological wonders of Grand Teton, Yellowstone and Badlands national parks; and the awe-inspiring

man-made Mount Rushmore National Memorial and Crazy Horse Memorial.

In between, we saw miles and miles of open country that, although beautiful in its own way, was mind-numbingly monotonous.

I could only imagine what the flat, open land did to the hardy folks who, in the mid-1800s, traveled west

day-after-excruciating-day by horseback and covered wagon. No wonder, then, that a tall rock formation could generate intense

excitement for them.

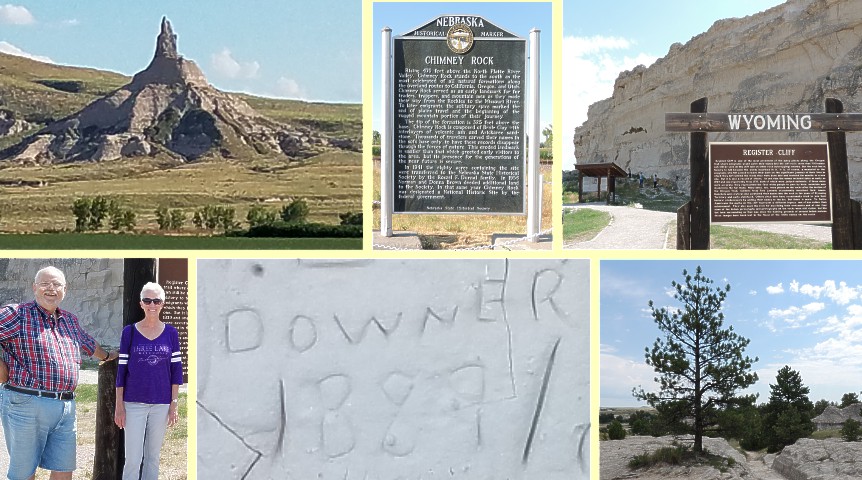

Although our travel was done in comfort, I admit to being thrilled, too, when we saw Chimney Rock near Scottsbluff,

Nebraska. We had traveled nearly eight hours, stopping once to get some lunch. I was very ready to get out of the car.

Chimney Rock, a prominent geological rock formation in western Nebraska, served as an early landmark for fur traders and

trappers and later for travelers heading west along the Oregon, California and Mormon trails. The “steeple” marked the end of

their plains travel and signaled the beginning of the more rugged mountain portion of their journey.

I read later that, prior to exploration by European immigrants, Native Americans of the area - mainly the Lakota Sioux -

referred to the formation by a term which meant “elk penis.” But, according to atlasobscura.com, even fur traders would use

euphemisms such as “Elk Peak” rather than the less-delicate Siouan name. The name Chimney Rock was first recorded in 1827 by

Joshua Pilcher, a trader and Indian agent in the area.

The next morning, we left Scottsbluff and proceeded north and west, stopping at Rifle Pit Hill just past Guernsey, Wyoming.

The historical marker there explained that rock quarries supplied lime and stone for construction projects at Fort Laramie

about 15 miles away. Soldiers protected the workers by digging fortified rifle pits into the hills. The sign also explained

that the nearby Oregon Trail Wagon Ruts and Register Cliff historic sites “... present strong visual evidence of the

500,000 westering pioneers who passed this way on their epic journey to Columbia River farm lands, California gold mines and

the religious freedom of the Great Salt Lake valley...”

I had wanted to see more Oregon Trail landmarks ever since we visited Alcove Spring near our home in Kansas when our girls

were small. The spring is located near Independence Crossing, where pioneers following the trail forded the Big Blue River.

The site is located about a mile west of U.S. Highway 77 at a point six miles south of Marysville, Kansas. One of the

travelers described the springs as “a beautiful cascade of water ... altogether one of the most romantic spots I ever saw.”

The ill-fated Donner-Reed party, most of whom later froze or starved in the Sierras, passed by the springs in 1846. Sarah

Keyes, one of the party, died while they were at Alcove Springs and is buried nearby. While deaths along the trails were not

unusual, in reality, they occurred at about the same rate as had the travelers stayed at home.

But while we pass the Alcove Springs area frequently, it seemed unlikely we would again be in Wyoming any time soon, so I

suggested we turn the car around and drive back toward Guernsey. Art agreed.

We followed the signs - and the other tourists - to Register Cliff, which rises more than 100 feet above the North Platte

River Valley. Immigrants traveling along the Oregon, California and Mormon trails camped near the chalky limestone bluffs on

the south side of the river, recording on the cliff's wall their names, dates of passage and hometowns. Many of

the inscriptions are from the 1840s and 1850s, the peak years of travel. Native Americans also inscribed pictographs and

petroglyphs on the cliff, but they and many of those from pioneer days have been obscured by the hundreds of names that have

been carved by more recent travelers. Register Cliff is one of the three best-known “registers of the desert” in Wyoming.

From Register Cliff, we drove to the Oregon Trail Ruts site along the North Platte River. The stretch we saw is said to be

the best-preserved anywhere along the trail’s length. The deep ruts - some more than four feet deep - were made by the wear

of wagon wheels and from the intentional cutting by people attempting to ease the grade from the level river bottom

nearby.

From there, the trail headed southwest and we were not. I said a silent farewell, but I was glad to have seen the

rocks, register and ruts connected to the history of our expanding western frontier created by the hardy travelers who

passed this way 170 years ago.