Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - March 17, 2017

The truth about Ireland

I’ll be wearing green today to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day. And I hung up the green construction-paper leprechauns

daughters Mariya and Katie made when they were in grade school. I also bought myself a shamrock plant as a centerpiece for

our dining table. I might even sing a few bars of “Danny Boy” - the haunting ballad that never fails to bring a few tears.

However, there will be no corned beef and cabbage, this year. I didn't have the time.

But I was prompted to learn how this all begin. I discovered the Feast of St. Patrick - in Irish, “Lá Fhéile Pádraig” -

was once just a simple religious holiday set on March 17, the traditional death day of Ireland's patron saint. The details of

his life are sketchy and mixed with myth. It is believed he was born into a wealthy Romano-British family late in the fourth

century. At 16, he was kidnapped by Irish raiders and taken as a slave to Ireland, where he worked as a shepherd and

“found God.”

I recently learned more about the holiday from an article by Mike Cronin, the academic director of the Centre for Irish

Programmes at Boston College in Dublin. The piece in the March/April 2017 “Saturday Evening Post” said many of the

customs we associate with Ireland actually originated in the United States. For example: while the world’s first St.

Patrick’s Day parade occurred on March 17, 1766, it was not in Ireland, but in New York City. It featured Irish Catholic

members of the British Army marching with fifes and drums.

The day grew in significance following the end of the Civil War and the arrival, across the 19th century, of

ever-increasing numbers of Irish immigrants. Facing nativist detractors who characterized them as drunken, violent,

criminalized and diseased, Irish Americans were looking for ways to display their civic pride and the strength of their

identity ... Through the use of symbols and speeches, Irish Americans celebrated their Catholicism and patron saint

and praised the spirit of Irish nationalism in the old country, but they also stressed their patriotic belief in their

new home ...

While Manhattan, Kansas has an official parade on or near March 17, the city's younger generation has embraced

“Fake Patty’s Day.” It is a weekend full of partying the week before the actual holiday and before the university closes

for Spring Break.

St. Patrick’s Day didn’t become an official public holiday in Ireland until the Bank Holiday Act of 1903. James O’Mara,

an Irish Member of the United Kingdom Parliament who introduced the measure, later sponsored a law requiring taverns be

closed on March 17 after drinking got out of hand. The latter act was repealed in the 1970s.

Is corned beef and cabbage of Irish origin?

According to www.history.com, Irish immigrants brought their own food traditions, including soda bread and Irish stew.

Irish bacon was the preferred stew meat, since it was cheap in Ireland. But in the U.S., pork was too expensive, so they

began cooking beef instead. Members of the Irish working class in New York City first tasted corned beef at Jewish

delicatessens. Because it was cured and cooked similar to Irish bacon, it was seen as a tasty and cheaper option with

cabbage being a cost-effective accompaniment. Cooked in the same pot, the spiced, salty beef flavored the plain cabbage,

creating a simple, hearty dish.

And “Danny Boy”?

The lyrics were written by Englishman Fred Weatherly, a song publisher. While the words of longing were moving, the tune

didn’t fit. In 1912, Weatherly’s Irish sister-in-law introduced him to the Irish melody, “The Londonderry Aire,” and a hit

was born. His lyrics for “Danny Boy” were published in 1913, just as tensions were building in Europe. When fighting broke

out the following year, the sense of longing in the lyrics struck a chord and the song's popularity has remained to this

day.

Surely the phrase, “the luck of the Irish,” is from Ireland!

Not according to Edward T. O’Donnell, associate professor of history at Holy Cross College, Worcester,

Massachusetts. The author of “1001 Things Everyone Should Know About Irish American History” said the phrase arose from

the gold and silver rush years in America's Southwest during the latter half of the 19th century. Irishmen such as Jimmy

Doyle, Jimmy Burns and Johnny Harnan were made rich by their Portland gold mine in Cripple Creek, Colorado.

The potato famine?

It occurred, but the impact was mainly in northwest Ireland. Most who left Ireland did so because they could no longer find

jobs in weaving due to industrialization. Ireland's population today is half what it was in 1840.

Some St. Patrick’s Day customs actually do come from the Emerald Isle. “The wearing of the green” is one of them.

According to folklore, Patrick used the three-leaved shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity to Irish pagans. Also, green has

been associated with Ireland since at least the 1640s, when the green harp flag was used by the Irish Catholic

Confederation.

All these elements joined together have now made the once quiet feast day into a celebration of all things Irish, not

to mention a marketing bonanza for businesses that sell green T-shirts, milkshakes, greeting cards, beer and candy.

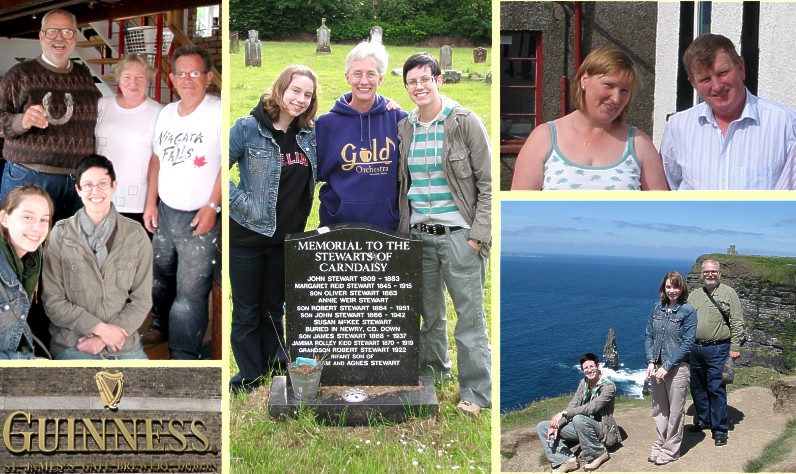

Before they left for America in the mid-19th century, my Freeland, Stewart and Shannon ancestors all called Ireland home.

So in 2008, husband Art, our two girls and I visited much of the island nation. We chatted with Kenny and Roberta Hunter,

who now live in the home where Robert and Rose Shannon, my great-great-great grandparents, had lived. The Hunters made us a

good-luck present of the old horseshoe from the shed door.

Our experience with the Hunters was typical. Perhaps Katie said it best when near the end of our trip after yet another

person had gone out of his way to help us. "What's wrong with these people?" she asked. "They're all so nice!"

It is true that much of what we believe about Ireland is untrue. But the reality is far nicer. So every year when St.

Patrick’s Day comes around, I pause and think of our time in that beautiful country.