Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - February 17, 2017

The right blend

A frequent problem when I’m writing a story is deciding what to include and what to omit. The primary test is what

contributes appropriately to the story - too much information becomes boring, and too little makes it incomplete.

But there are other related dilemmas. Several concern quotes. The way we speak one-on-one, if converted directly to

a written quote, often doesn’t measure up to what we expect to see in print. So should the writer correct small

grammatical imperfections? And if it is corrected, is it still really a quote? If not corrected, does the incorrect

grammar make the speaker look like a bumpkin? This predicament has been compounded in the past decade or so as people

frequently now use text-messaging to respond to interview questions. Texts often use truncated phrases which do not

meet the accepted standard for prose. When these are mixed with the unintended changes created by automatic spelling

correction software on most smart phones, a whole new batch of problems appears.

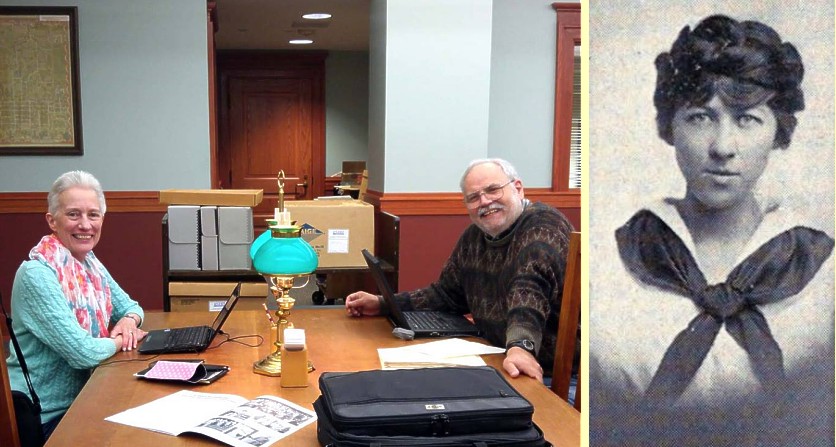

But recently, I have been wrestling with a different sort of problem that I have encountered infrequently before.

Husband Art and I have been researching Velma Carson, a woman who finished her college work early in the 20th century.

She went on to a very successful career as a writer. Along the way, she met prominent people in the fields of business,

the arts and politics. Many of these blossomed into friendships. The combination of her colorful life mixed with a

pool of interesting people has prompted us to consider writing a book about her.

Since Carson died more than 30 years ago and her only child is also gone, we have been reduced to questioning those

who knew her and reading every item in her well-stocked archives. The latter was donated to Kansas State University by

her son-in-law.

While it has many examples of her work, both published and unpublished, the bulk of the material is correspondence -

much of it between family members. And just as with letters I have written to my parents, siblings or children, many

contain very personal things. A number of Carson’s letters contain some variation of the admonition, “Burn this after

you read it!”

While these letters contain no state secrets and most of the people mentioned are no longer living, I cannot

completely escape the sense of being an uninvited eavesdropper. Certainly, the act of donation puts them in the public

domain. And having come to know our subject as well as we have, far from being offended, I’m pretty certain Carson would

be pleased with the posthumous attention.

Yet there remains something reminiscent of the emotion I had a few years ago when we ran across a picture of Art’s Mom

Donna. It was taken while his family was in Chicago on vacation where they had encamped at Donna’s sister’s apartment.

Donna had picked up the newspaper and retired to what might be euphemistically called “the reading room.” Art was able to

snap a deer-in-the-headlights picture of her before she could stop him. The resulting photo, though harmless, was

simultaneously funny and slightly unnerving. The latter emotion came from a sense of having crossed some invisible social

line.

When I read newspapers from the early part of the 20th century, it is clear that any direct mention of sex or sexuality

was unacceptable ... it was over the line. Most small-town editors did whatever they could to avoid mentioning such matters

as rape. If there was no escaping the fact, some euphemism was employed. A common one was to say the woman in question was

“outraged” ... which I’m sure she was. This example illustrates another aspect of this problem: the line’s location may

change over time.

In contrast, no level of detail about violence was considered over the line. Art told me about a man who committed

suicide by sitting on a case of dynamite and lighting the fuse. The newspaper coverage described the scene in some

detail, down to telling what body parts were found hanging in the nearby trees.

In comparing these two ... sex and violence ... it seems that, after a century, they have swapped places in regard

to where the "too far" line is located.

One of the points I impress on the budding journalists in my class is to try to add a human touch to every story.

Interviewing someone involved adds credibility. But in a historical tale, all the main characters may have passed away.

So the next-best thing is to contact people who knew the ones who died. If all else fails, a noted figure in the subject

area can still raise the subject above the level of a textbook discussion.

So what to do! Adding the human aspect does for a story what spices do for a meal. Too little, and the result is bland;

too much and it overshadows the main course. So I need to implement the idea I tell my students all the time: good writing

has to have just the right blend of ingredients to be appetizing to the reader.