Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - October 24, 2014

An important anniversary

An important anniversary slipped by last month and it passed almost unnoticed.

The American revolution might be considered the starting point for this story and one part of that tale we like

is its David-and-Goliath aspect. It leads us to think of ourselves as pretty resourceful, what with been able to

break away from Great Britain when it was on its way to becoming the world's most powerful nation.

But more was involved than just our being resourceful. In the late 18th century, France and Spain were also vying

to be the world's dominant power. Since often "the enemy of my enemy is my friend," France openly helped our young

colonies, hoping they could preoccupy some of Britain's military might. Spain also helped, but since it didn't want

Britain attacking its gold and silver-rich colonies in Mexico and South America, its aid, such as slipping us barrels

of gunpowder, came under the table.

Britain eventually decided the price of keeping its North American colonies was too high, but the British tussle

with France continued. The U.S. had no desire to be involved, but the Royal Navy developed a habit of capturing

American trading vessels, abducting the crews, and then putting them to work on British ships. By 1812, America had

enough of it and declared war on Britain.

After a couple of years, the British decided that we American upstarts needed to be taught a lesson. In September

1814, the Royal Navy headed up Chesapeake Bay, intent on attacking Baltimore. Two things stood in the way - a string

of ships purposely sunk to block the channel and Fort McHenry, which sat on a point that protruded into the bay.

The previous August, the British had captured Washington. Prisoners of war were a pain to guard and provide for, so

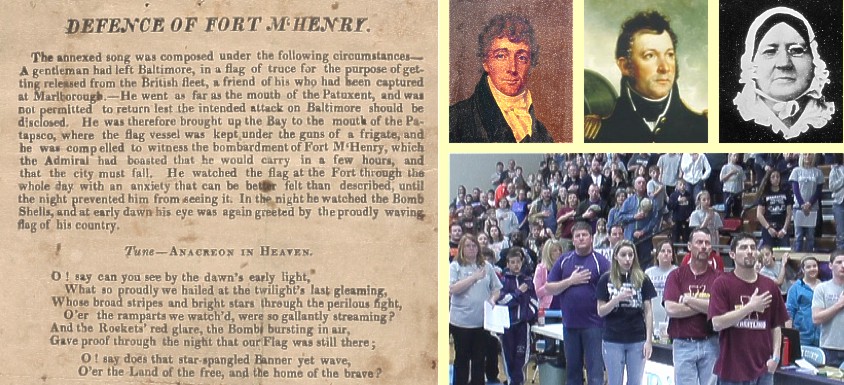

it was common to trade them for any men the enemy held captive. In mid-September, 36-year-old lawyer and Maryland

native Francis Scott Key had been brought aboard the British ship Tonnant to help negotiate a prisoner exchange.

But a problem developed. British commander Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane decided he was going to attack Baltimore.

The British were afraid if they allowed Key and the others to return, they would inform the Americans of details of the

British strength and strategy. Hence, they were detained.

Fort McHenry's commander Major George Armistead was no shrinking violet. In 1813, he had done well with the

Americans who defeated the British near Niagara Falls. In a sort of stick-it-in-your-eye gesture, he had asked

Baltimore flag maker Mary Pickersgill, 29, to make him a flag that could be seen at a great distance. All through our

revolution, no flag had been widely adopted, so there was room for innovation. But stars and bars had been frequently

used, so it was decided this flag should have 15 stripes and 15 stars - one each for each of the states. Pickersgill

and several others labored to produce a monster 30-feet high and 42-feet wide. Each star was two feet across. This

"star spangled banner" was delivered on Aug. 19, 1813, just five days before the city of Washington fell.

The British began shelling Fort McHenry before dawn on Sept. 13 and continued for 25 hours at a rate of more than one

cannon shot per minute. When the sun rose on Sept. 14, Key expected to see the Union Jack flying over the fort. Instead,

he saw Pickersgill's flag. And since the British had expended their munitions, the battle was over. Key, having been

an amateur poet for many years, then penned on the back of a letter the words Americans now call "The Star Spangled

Banner."

His original has never been found, and it is unclear if Key even had a title for the work. After adding additional

verses, Key had several copies printed, two of which survive. The sheet is titled "Defence of Fort M'Henry," with an

introductory paragraph explaining the conditions under which it was written.

The music was borrowed from "The Anacreontic Song," a piece from the late 18th century composed as a sort of theme or

drinking song for an amateur group of English musicians. It was not intended as a serious piece, being thought of in a

similar fashion to Yale University's "The Whiffenpoof Song." And like that piece, it was known far and wide so it was

conveniently available for Key's use.

In 1916, more than 100 years later, President Woodrow Wilson declared "The Star Spangled Banner" to be our national

anthem. In 1931, Congress passed a similar resolution affirming Wilson's executive order. President Herbert Hoover

made it official.

As for the flag, it continued to fly over the fort where Armistead remained in command until his untimely death just

three years later. It was then given to his widow, who began giving pieces away as souvenirs. After her death, other

relatives did the same and slowly the flag became smaller. In 1907, the now 30-foot by 34-foot flag was donated to the

Smithsonian, where it remains and can be viewed to this day.

This past Sept. 14 marked the 200th anniversary of "the dawn's early light" that revealed Old Glory was still

"so gallantly streaming." And while our flag has changed in appearance during that time as new states were added, the

song has remained as Key wrote it.

Happy birthday, "Star Spangled Banner!"