Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - October 10, 2014

Lemons to lemonade

This past week, I was in a city I hadn't visited in 15 years. During that time, I had forgotten what a treat it was

to experience one of its principal features. But this time, rather than just enjoying it, I investigated its history.

What I discovered was the story of a man ahead of his time, but who lived long enough to be recognized for his vision.

All cities need a reliable source of water to survive, but if that source is a stream, river or lake, it is often a

double-edged sword because an unusually heavy rain can lead to flooding. In September 1921, San Antonio, Texas had this

unpleasant occurrence. The city's officials wanted to make sure it didn't happen again. So they decided to bypass the

loop of the river that passed through the downtown area and then fill that loop in.

While the bypass was under construction, conservationists were successful in stopping the remainder of the plan. But

stopping is not defeating, and it still might have moved forward if it weren't for the Depression that made finding funds

for such projects difficult.

At age 27, San Antonio architect Robert Hugman had a different vision. He proposed controlling flooding in the loop by

adding gates where it reached the river and then transforming the lands adjacent to the loop into an urban attraction. But

lack of money and the notoriety the area had for its high crime rate meant little happened.

While few besides Hugman could imagine turning this lemon into lemonade, the Depression that had contributed to halting

any work would ultimately also be what fostered that transformation. After the stock market collapse in 1929 and the

subsequent downturn in the economy, President Herbert Hoover began pushing for combined private sector and government

programs to put people back to work. Presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt criticized Hoover's proposal as being far

too expensive. But Roosevelt had hardly been sworn into office when he began following Hoover's blueprint. For San

Antonio, it was the Works Progress Administration, later changed to Work Projects Administration, or WPA, that would come

to the rescue. Men who were supporting families but couldn't find work were hired to complete various public-good projects.

The National Youth Administration, or NYA, was part of the WPA, but it offered various work projects to young single men

and women.

The loop project received WPA funding in 1938, but the actual work had barely began when Edwin Arneson, the WPA's area

administrator and a huge Hugman supporter, was discovered to have cancer and soon died. San Antonio Mayor Maury Maverick

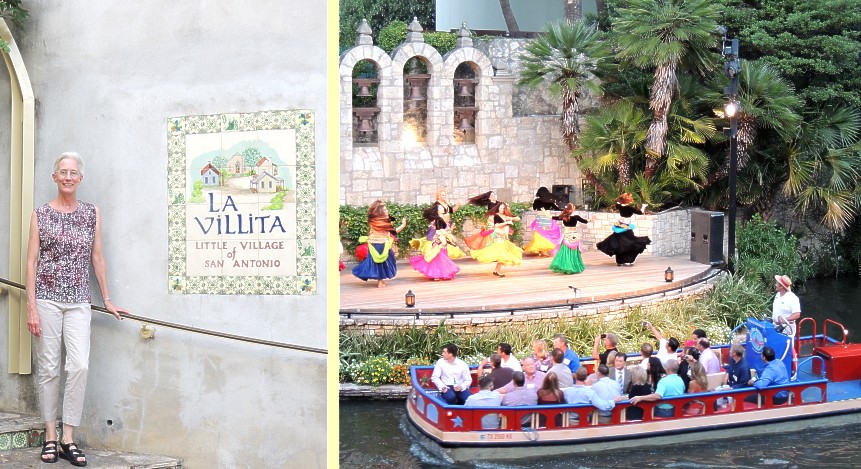

pushed forward with his pet NYA project adjacent to the loop, the restoration of the historic "La Villita" area. Hugman

discovered materials for his River Walk enterprise were being diverted to Maverick's restoration. Hugman presented proof

to the River Walk board, but politics being politics, his reward was being fired as chief architect.

But the project moved forward. The WPA workers constructed more than three miles of walkways along both sides of the

old river loop, built 20 bridges across it and planted thousands of plants and trees along its banks.

Even with the main work completed, progress was slow because concerns over safety persisted. Hugman's faith in the

project was such that he built his private architectural firm next to the loop. Eventually, fears faded and growth began

at a steady pace. By the 1960s, the area became so attractive that the original loop couldn't provide enough venues

near the water's edge for all those who wanted them, so the first of several artificial channels was added.

I first saw the San Antonio River Walk when I was there for a conference. Last week, I returned for yet another

conference, but this time husband Art tagged along.

Despite temperatures in the mid-90s and humidity numbers to match, we had fun strolling along the now-famous River

Walk. The pathways are about 10 feet below street level and the air was noticeably cooler. It was easy to avoid the direct

sunlight. With the summer tourist season over, the numerous restaurants had no shortage of space. We chose outdoor seating

at the Caf� Ol� and had our pick of tables. Soon, we were joined by two other groups.

With our appetites satisfied, we walked to the San Fernando Cathedral just west of the river. Built originally by

Spanish settlers from the Canary Islands, the beautiful church dates to the first half of the 18th century and is on the

National Register of Historic Places. A large chest at the far southeast corner of the building is believed by some to be

the final resting place for the remains of some of the defenders of the Alamo a few blocks to the northeast.

San Antonio's El Mercado - another WPA project - was a few blocks farther west. We wandered through the many small

shops in the enclosed mall, most brimming with various goodies for the "Day of the Dead" celebration that we Kansans call

Halloween. When our feet asked for relief, we crossed the street to the Mi Tierra Caf� and relaxed with some flan and

fried ice cream.

On the approximately one-mile return journey to our hotel, we decided to take the southern portion of the old river

loop. One of the most unusual sites we encountered was the Arneson Amphitheater, named after that WPA boss. The seating

area is to the south with the stage to the north. What makes it unusual is the river loop passes between them!

Behind the stage is the Robert Hugman bell tower with five bells, one for each of the city's original missions. As for

Hugman, it must have been some significant confirmation of his dream to be asked to be the first to ring the bells in

1978, 49 years after he presented his original River Walk proposal and two years before his passing.

As for Maverick, his venture succeeded as well. La Villita was home to a Coahuiltecan Native American village in the

early 18th century. The almost 2,000 NYA youth who labored there created an area now home to an arts and crafts

community.

The WPA and many other of Roosevelt's New Deal programs were controversial at the time. Some that have persisted, such

as Social Security, remain the subject of debate to this day. Critics claimed that the WPA workers were lazy and didn't

earn the going-rate wages they were paid. But whether those accusations were valid or not, looking around San Antonio's

River Walk area and some of the other projects the WPA had a hand in, there is little doubt that at least in these cases,

those WPA monies turned lemons into lemonade.