Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - June 6, 2014

Stories of sacrifice

It was a peaceful place. Birds sang. People spoke in hushed tones, interrupted occasionally by a small child giggling. Groups of school

children stopped now and then to take notes. But 70 years ago on this same hill facing the English Channel, hundreds of men lay dying or

had already died. In some planning session far from here, the beach had been given the name Omaha - one of two beaches the men of the

United States were to take on June 6 to begin the liberation of Europe from Nazi Germany’s grip.

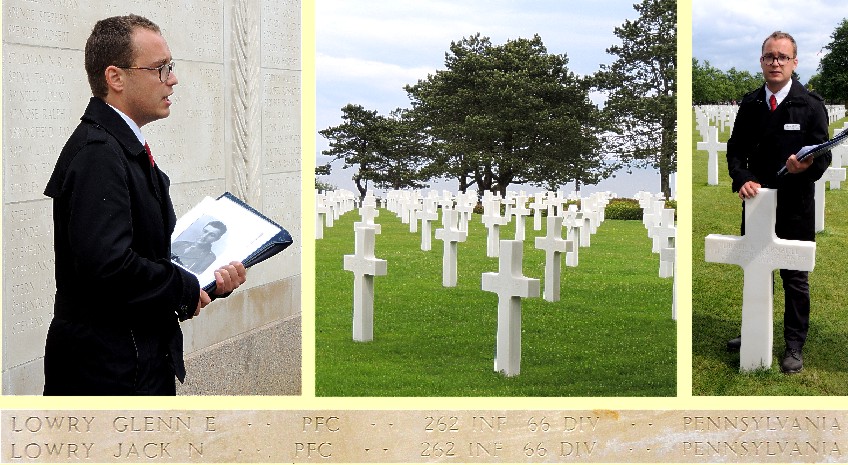

The nearby cemetery covers 172.5 acres and contains the graves of 9,387 U.S. military dead, most of whom died in the D-Day landings

and subsequent operations. Guillaume, our cemetery guide, showed photos and shared a few stories of the men who never went home.

He began at the semicircular Walls of the Missing with its 1,557 names. A few are marked with small bronze rosettes to indicate those

whose remains were eventually recovered and identified.

One of those was Army Staff Sgt. John R. Simonetti, 26, of Jackson Heights, N.Y. Simonetti had been born to an Italian family who had

the misfortune to come to the United States seeking a better life just before the Depression began. Since his father was unable to feed his

large family, John decided to join the Army.

According to an Army press release of a few years ago, on June 16, 1944, he was among the advancing infantrymen of the 9th Infantry Regiment

of the 2nd Infantry Division. They were met with heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire and stopped to take cover near the French town of St.

Germain-d’Elle. Simonetti was killed. One witness said Simonetti’s body could not be recovered and another said his body had been evacuated to

an aid station. A military review board classified him as non-recoverable.

Then in May 2009 while excavating a site in St. Germain-d’Elle, a French construction crew uncovered human remains and military materials -

including Simonetti’s identification tags. Scientists from the Joint POW/MIA (Prisoner of War/Missing in Action) Accounting Command used dental

comparisons to positively identify him.

But Simonetti is the exception. At the end of the war, the U.S. government was unable to recover and identify approximately 79,000 Americans.

Today, more than 74,000 are still unaccounted for.

Among those are twin brothers Glenn and Jack Lowry. Both had graduated from Rostraver Township High School 30 miles southeast of Pittsburgh

and then had gone to work in the same department of a steel mill. They entered the army in 1943 and were Privates First Class with the 262nd

Infantry Regiment, 66th Infantry Division.

They died when the Leopoldville, their transport ship crossing the English Channel to Cherbourg, France, was hit by a torpedo from a German

submarine late on Christmas Eve 1944. Both were officially listed as lost on Dec. 25, 1944. Losing a son would have been hard enough, but to

lose two - and on Christmas Day - must have been almost unbearable for their family.

Guillaume then led us to the white cross marking the spot where Turner Turnbull is buried. Turnbull, a half-Choctaw, was born in Durant,

Okla. and spent many of his growing-up years in Colorado. He attended Haskell Indian School in Lawrence, Kan. He then returned to Oklahoma

to attend school and later joined tha National Guard.

Turnbull became a paratrooper in the elite all-volunteer 82nd Airborne Division and served in the African, Sicilian and Italian campaigns.

In the invasion of Sicily, Turner’s plane crashed, probably shot down by friendly fire. He received a gunshot wound to the abdomen and was

hospitalized in England for four months. Guillaume said Turnbull could have gone home, but instead he decided to rejoin his men for the D-Day

invasion.

His 2nd Battalion of the 505th Regiment parachuted into France behind enemy lines early on D-Day morning. Turnbull and his men were ordered

to capture the village of Neuville-au-plain about a mile to the northwest of Ste. Mere Eglise and set up a defensive line to protect it. A large

column of what looked like German prisoners of war being led along the road turned out to be a ruse. The Germans had taken a number of American

paratrooper uniforms and attempted to pass this main column off as German prisoners in the process of being surrendered. But they soon began

attacking and Turner and his men responded, holding the Germans at bay for about eight hours in spite of being extremely outnumbered. Their

defensive actions have been cited as being crucial to the Allied success in Normandy.

On the morning of June 7, Turner was killed by German mortar fire. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Guillaume is a young man, born long after World War II ended. Yet he was obviously touched by the stories he had shared. With his hand on his

heart, he expressed his deep appreciation to the American people for their sacrifices during World War II.

Looking out over the perfectly-positioned Latin crosses and Star of David markers, I shared his feelings and was humbled by the terrible

sacrifices made. Britain’s war-time Prime Minister Winston Churchill was noted for his ability to choose just the right words

at important times. Some he had used to praise his air force applied here as well: “Never was so much owed by so many to so few.”