Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - April 4, 2014

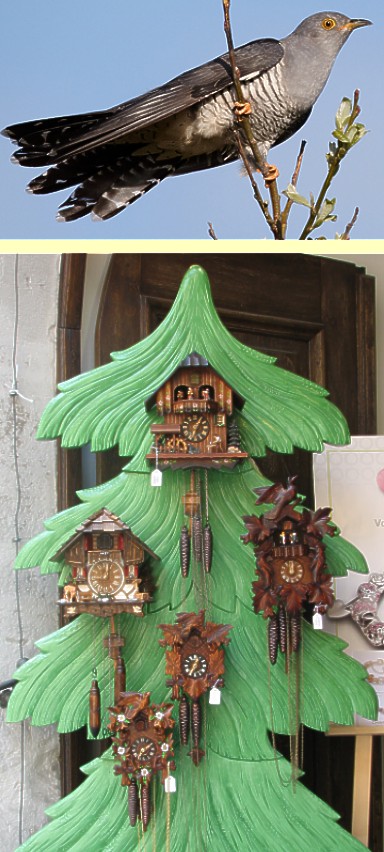

Cuckoos aren't so crazy

When I grew up in Kansas, we had no shortage of feathered friends. Hawks patrolled the skies during the days

while owls kept the rodents in check at night. On sunny days, yellow and gray meadowlarks perched and sang on fence

posts along the edge of country roads.

Many of us heard one particular bird, but never saw it. Almost all of us knew someone who owned a cuckoo clock,

but none of us had ever seen a cuckoo. The reason, of course, was that this bird with the unique call is not native

to North America. Cuckoo clocks aren't either. They are the product of German, Austrian and Swiss clockmakers who

labor in places where cuckoos are common.

For me, it was a treat during my first visit to England in 1988 to hear the call that I had never before heard

coming from anything but a clock.

But during subsequent trips to both Britain and Europe, it became obvious that the locals were not nearly as

enamored with the bird as I was. And their distaste was not because of the species' rather drab appearance. Instead,

it had to do with its inhospitable nature and questionable parenting skills. Unlike most of its fellow avians, the

female cuckoo deposits its lone egg into the nest of another bird and then leaves, washing its wings of any further

parental duties.

Whether it can be called a bad parent is open to debate, for the young cuckoo grows to adulthood quite successfully

in its chosen home. Research conducted a few years ago at Sheffield University in England showed that the female cuckoo

incubates the egg internally for a full day before laying it in the nest of an unsuspecting neighbor. This last act by

the mother gives the cuckoo youngster a head start on other nest hatchlings.

Some idea of how the cuckoo's strategy is viewed by the Brits can be discerned by the way the report summarizes

its contents as "solving for the first time the mystery as to how a cuckoo chick is able to hatch in advance of a

host's eggs and brutally evict them."

The image of dropping your young off at a neighbor's house and then never returning while that offspring pushes

the neighbor's kids out of the way is not a recipe for winning any hospitality award.

But it also may be an unfair characterization. If a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, maybe a little

research is a bit too brutal in its conclusion.

A recent article in the journal "Science" was described on National Public Radio. The article reported that

researchers in Spain discovered a curious result when they did a study of crow nests that were often the target of

an uninvited cuckoo egg. When comparing the survival rate of crows in nests with cuckoo eggs with nests not

containing the foreign eggs, they found it to be higher in the former case. How could that be if the young cuckoos

were somehow edging out the offspring of the nest owners for food?

At first, researchers thought maybe the cuckoo mother might have some special talent that allowed it to better

discern which were the better crow nests or crow parents. In other words, maybe the cuckoo mother was borrowing a

trick sometimes used by humans, leaving unwanted children on the doorsteps of the well-to-do, rather than those

barely getting by.

To test that notion, they took cuckoo eggs from the nests they had been laid in and placed them in other crow

nests. What they discovered was that better survivability moved with the cuckoo egg. This uninvited

egg-on-the-doorstep actually made it more likely that the crow chicks would reach adulthood.

After more study, the reason was uncovered. It appears that crow nests are heavily victimized by cats. But a

young cuckoo gives off a noxious substance when stressed that puts the cats off. Even a small amount on a piece of

raw chicken caused cats to turn away.

In the spirit of full disclosure, more research of my own revealed that there are different varieties of cuckoos

and many do not exhibit this helping-hand approach to nest-mates. In fact, some indeed do as the English researchers

described and summarily rid the nest of competitors.

I also learned that English cuckoos have another trick up their feathers. They commonly lay their eggs in the

nests of reed warblers. The warblers respond by banding together to attack cuckoos. But young warblers learn what

a cuckoo looks like by watching their older neighbors. So the same species of cuckoo have evolved to produce gray

and reddish versions. While the local warblers are ganging up on the coloration their kind have come to recognize,

the cuckoo with the alternate coloration is busy laying its eggs in warbler nests.

All of this makes me wonder why calling someone "cuckoo" has come to mean they are crazy. These birds might not

be model neighbors, but they sound pretty clever to me.