Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - March 29, 2013

My brain on music

Ever since youngest daughter Katie, now a college sophomore, became involved in music, I feel like I have music on my

brain even more than before.

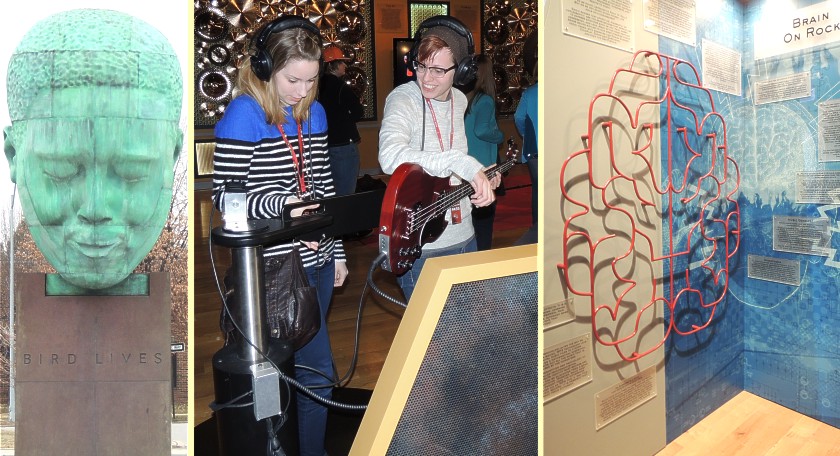

Last week was no exception. Katie, husband Art, daughter Mariya, daughter-in-law Lacey and I were in Kansas City for

Spring Break. While there, we visited the American Jazz Museum and "The Science of Rock 'n' Roll" exhibit at Union Station

and attended a performance of Rodgers and Hammerstein's "Carousel." In addition, Art and I stayed up late one night watching

two parts of a television series on the Eagles, a Rock 'n' Roll band I loved in the 1970s and '80s.

Our week-long immersion into music actually began the Friday before break. We had heard the Celtic Tenors' Christmas program

at Kansas State University's McCain Auditorium about 18 months earlier. On March 15, they returned for an encore performance.

I loved them the first time - and I loved them even more the second time around.

I think music touches the emotions in many ways, and the tenors' performance certainly did that for me. When they sang

"Remember Me - Recuerdame," - a song about a soldier asking his sweetheart to remember him while he's at war, the tears spilled

down my cheeks. In contrast, when they had the audience participate in the grand opera piece, "Nessun Dorma," I couldn't stop

smiling.

During the intermission, Katie had a question that surprised me.

"Doesn't it make you sad that you can't listen to music while you're doing other things?" she asked.

She knows me all too well! She knows that I can't read or do any work that requires concentration if music is playing in the

background.

"Not at all," I responded. "It's too distracting when I'm busy, but that means that when I do listen to music, I REALLY

listen!"

Still, that conversation and the Union Station exhibit prompted me to think about music and the effect it has on our brains.

I've heard about studies that seem to show a positive effect music has on such things as learning, creativity and even healing.

What mother doesn't know the value of certain music to calm an agitated baby? And quick marching music has long been used by

the military to encourage troops to push on to victory.

At the exhibit, I acquired a new musical term. It describes something I and the majority of others have been afflicted

with at times - the earworm. While the name is a bit off-putting, its meaning is far more benign. It refers to several bars of

music that keep repeating in the brain over a long time. It usually occurs with a piece that was heard recently. It might be

that last song a person hears on the radio before getting out of the car or some jingle accompanying a television commercial.

The actual music ends, but it keeps playing on in your head over and over and over.

No one knows for certain why this occurs, but several researchers think it has something to do with our short-term audio

memory combined with the brain's amazing ability to recognize patterns. Research has demonstrated that if we are exposed to a

few notes of a melody we recognize, our brain will append more to them. But in the case of the earworm, the end of the part we

remember apparently triggers the beginning, leaving us in a loop. This action gives rise to the alternate name "stuck-song

syndrome."

For most people, the short-term audio memory is somewhere between 15 and 30 seconds in length and that corresponds to the

length of most earworms. While they sound rather dreadful, most people experience them at some time and most describe the

experience as somewhere between pleasant and not bothersome. The "Remember Me - Recuerdame" tune has been playing in my brain

since the concert and it isn't bothering me yet.

While researching earworms, I encountered a number of studies that have sought a correlation between traits such as

intelligence and musical preferences. One involved using the favorite music choices listed on the Facebook pages of college students

and pairing them with the school's average SAT scores. Correlations were found to exist, but what they mean is unclear.

In addition, there is a big difference between correlation and causation. When I was a young mother, some folks promoted the

notion that if you had your baby listen to classical music, he or she would grow up to be more intelligent. In the experiment,

students from schools with higher SAT scores were more likely to prefer Beethoven over Little Wayne. But that doesn't mean that

listening to Beethoven will make you smarter.

One thing we can say with certainty is that we live in an age when, more than at any time in the past, scientific tools are

being employed to understand how our brains function. But when it comes to something as common as music, we don't even know why

human beings enjoy it at all.

So, after a week virtually steeped in listening to and learning about music, all my brain could conclude was it was all

music to my ears.