Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - March 8, 2013

Sidetracked in Industry

"I got sidetracked in Industry, Kan.," I said.

The expected pause followed.

Then the voice from my cellphone asked, "There's an Industry, Kan.?"

I smiled. Two months earlier, I had never heard of it either.

I was due back at the university for a 3 p.m. meeting, but I had let the time slip by quite unnoticed. When

I realized how late it had become, I tried calling from Industry, but my phone indicated there was no service.

"I'll drive to the top of the hill up ahead and you can try there," husband Art had suggested.

That worked. My boss and I rescheduled our meeting for an hour later.

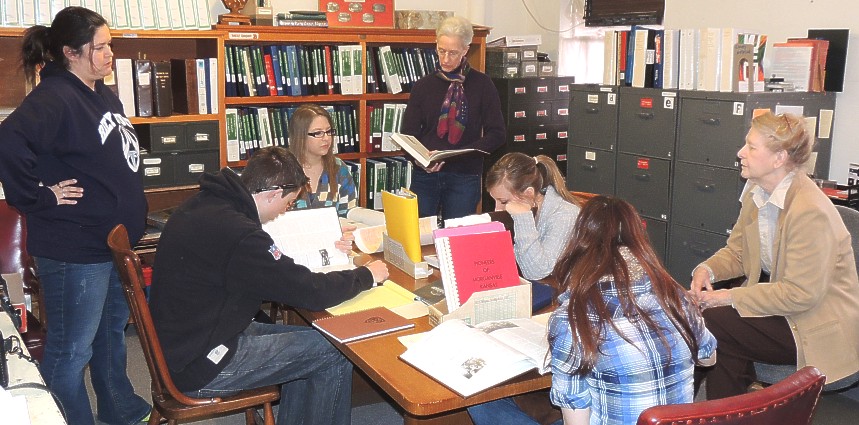

That was last Friday. The day had begun by Art and me meeting some students from my News and Feature Writing

classes in the parking lot of a grocery store on Manhattan's west side. But my motivation for that meeting

stretched back to last spring. It was then I had learned of the Chapman Center for Rural Studies' desire to

document the history of the small rural towns of Kansas. Always looking for "real world" experiences for my

students, I decided to organize the class into teams of three to work on some of the hamlets of Mark Chapman's

Kansas home county of Clay.

Since Art enjoys history as much as I do, he had decided to tag along on the 40-mile journey to the Clay County

Historical Society museum in Clay Center. Dakota, one of my students, rode with us, while two more followed in

another car. Others drove on their own.

Kansas, like most states, is going through a slow de-population of its rural areas. Many counties, such as

Clay, reached their population peak near the end of the 19th century and have been losing inhabitants steadily

ever since. Better and bigger farm machinery means it takes fewer people to plant and harvest the land's crops.

With smaller numbers of farmers and better transportation to larger towns like Clay Center or Manhattan, the small

villages of four or five blocks with their local banks, post offices and stores are no longer needed. In Kansas, a

few others were inundated when the large flood-control reservoirs were constructed in the 1950s.

The museum is housed in the old hospital. It contains furniture, household goods, tools, farm relics, old TV and

radio sets, X-ray machines, model train cars, dishes, surgical instruments, business signs, jewelry, clothing and a

wide variety of other items. Probably the most unusual one was a five-pound hairball removed from a cow's stomach.

Some of the rooms were devoted to specific communities. Teams assigned to one of those towns might have so much

material that their problem will be figuring out what to use and what to set aside. Others, such as the one assigned

to Deweyville, could scarcely find even a mention of their community on the Internet.

Industry was more like one of the latter. It was also the town Dakota was working on. Art, already intrigued,

suggested we should visit it before returning to Manhattan. So after several hours at the museum and a stop at the

local Wendy's for a bite to eat, we headed south on Kansas Highway 15.

About 17 miles later, we were surprised to see a highway marker for the town. We turned west and two minutes

later we arrived.

Only a few structures remain. The Methodist Church seems to be in good shape and still in use. A brick building

with the capstone "No. 402 IOOF (Independent Order of Odd Fellows) 1935" still stands proud.

Yet many of the buildings were weathered and had not seen any paint for decades. A few were sided with nailed-on

insulation.

Turning north on what one old map had indicated was Main Street brought us to a home constructed with a facing

of beautiful decorative stone that stretched from the ground to about waist high. It looked as if it had been set

only a few years ago. But above that level, the wood was black from exposure and lack of paint, the windows were

gone and the roof had caved in. The trees and other growth would have almost hidden the structure in the summer,

despite it being only a few feet back from the road.

Farther along, we came to what appeared to be a schoolhouse that had been converted into a home. It was connected

directly to a large building that may have been a barn.

We returned to the county road and turned west so we could view the village from its western side. A vehicle

approached heading east and passed through without stopping.

Whatever need Industry had fulfilled had since faded and one portion of the project will be for the students to

accurately report its current condition. But I also want them to find the Industry that was once a vigorous and

vital component of Clay County. I want them to find the Industry that once hosted the LWS - the Little World Series

- of fast-pitch baseball that brought farmers into town from miles away.

And I want them to do the same for Deweyville, Fact, Garfield Center, Green, Hannibal, Idana, Morganville, Oak

Hill and Vining - the hamlets that glued the otherwise isolated farmers into local interdependent communities.

The background research will take time, and many of my students will be uncomfortable interviewing folks three

and four times their age. But it will be good training for the day when they are faced with a story that is

difficult to write because they have too much or too little information.

And who knows, perhaps they, too, will become sidetracked following where the story leads them.