Kansas Snapshots by Gloria Freeland - Aug. 20, 2010

Viva Veva!

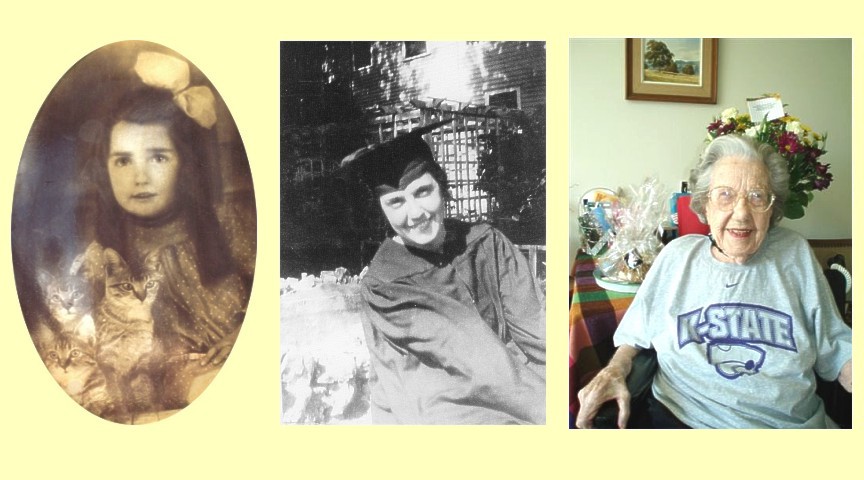

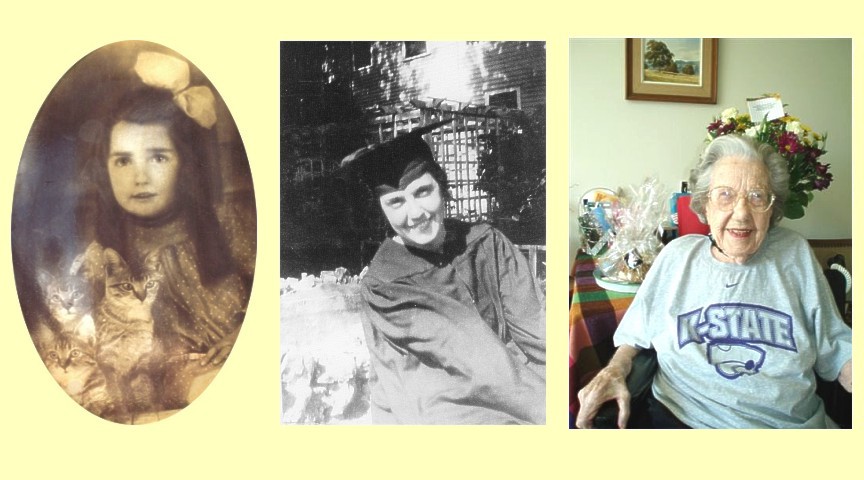

The little girl in the 1910 photo wears a polka-dot top and has a big bow in her hair. Her right arm cradles three striped cats.

Veva May Brewer Mann is not a relative, and I only recently "met" her via e-mails from her daughter Vicki Paul. But I feel that I have come to know her, if only just a little.

She was born on a homestead near Mount Hope, Kansas on Aug. 15, 1906. In 1912, her family moved to a homestead near Big Sandy, Montana. Later, they moved to Havre, Montana where Veva graduated from high school in 1924.

The family soon returned to Kansas where Veva attended business school in Wichita. With her newly-acquired Gregg shorthand skills and an ability to type 95 words per minute, she landed a job working for the Land Bank in Wichita.

But a Sunday dinner at the home of a tentative fiancé proved to be a life-changing experience. Veva noticed that the men spent the day visiting and reading the paper, while she and the young man's mother cooked and cleaned in the hot, steamy kitchen. Then, just when she thought they were done, the young man's mother put more water on to heat. When Veva asked why, the woman said it was time to begin preparations for the next meal.

"We broke up that day," Veva said. "I was never in that situation again."

College began to look more interesting to her, although most people couldn't understand why a girl would want to go to college.

Nevertheless, she entered the journalism department in September 1929 at what was then Kansas State Agricultural College. The beginning of the Depression the next month meant she had to work a variety of jobs to make ends meet throughout her college career.

Russ Thackrey, one of Veva's journalism teachers, covered the football games for the Associated Press wire service. He suggested she do the same for United Press International. Since she wasn't familiar with the game, he sent her to Coach Mike Ahearn, who taught her the game right before the season started, explaining plays while the team practiced. She worked the press box for nearly every home game over the next four years.

Kedzie Hall was where the journalism classes were taught and it was the only building on campus that had fireplaces - one on the main floor and one right above it on the second floor.

"We made cocoa in the ground-floor office," Veva said. "Every day at 4 o'clock, a few of us went in there. Kedzie did not have a dining room, so some of us took something in to eat ... It was hard to find a place to heat the milk (for drinks or cocoa.) There was a burner in the back room to heat the glue needed in print jobs. The only place to heat things was either on that or in the fireplace if you wanted a snack."

"One time my mother drove up to Manhattan in a borrowed car. Now that took a lot of courage," Veva said. "She filled the back seat with things to eat. This included a lot of jars of canned fruit and other things to eat."

Her mother wasn't much of a driver, so Veva asked her how she handled the stop signs. Her mother replied, "What stop signs?"

Veva interviewed newspaper icon William Allen White, who was on campus to deliver a speech. She was nervous when she met him backstage and there was no place to sit. But he dusted off a window ledge and lay his handkerchief there for her to sit on. She said he practically dictated her article about him.

Prohibition was still in effect when Veva was in college. Nelda, one of Veva's friends, gave her a gift of two small bright red glasses about an inch and a half high with a quarter that fit into the bottom of each. The girls had probably been to a speak-easy. Nelda's note with the glasses said there was enough to buy a drink once Prohibition was over. The girls had met the first day of school and Veva remained close with her and with others who were seated next to her in class.

When Veva graduated in June 1933, she borrowed a cap and gown. She couldn't afford a professional graduation photo, so she had someone take a snapshot of her. She graduated owing $250, which her daughter said "scared her to pieces," but she still paid extra to have her diploma hand-lettered.

She went to Los Angeles in 1938, hoping to land a job at the Los Angeles Times. But the wage was $60 a month and she needed $85 to survive. So she again took a job at the Federal Land Bank and married her boss in 1940.

A more recent photo of Veva at her home in Ventura, California doesn't include any kittens, but she is wearing a K-State Powercat sweatshirt while smiling brightly for the camera.

Last Sunday was Veva's 104th birthday, and I believe she's the oldest living graduate of K-State's journalism and mass communications program, which is celebrating its centennial in September.

Viva Veva!